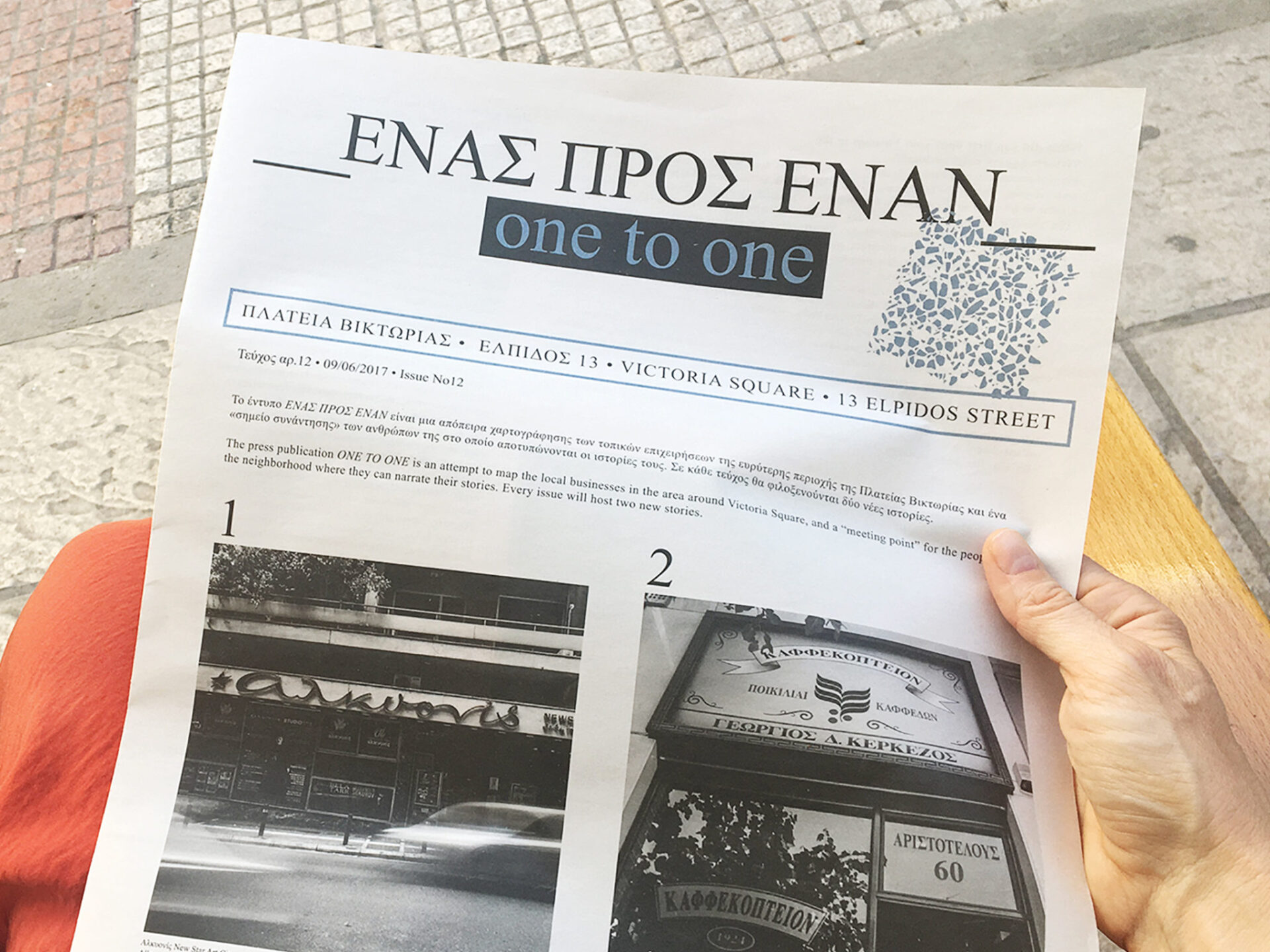

“Victoria Square Project” produces the newspaper “One to One” to map Victoria Square’s surrounding neighborhood through interviews with local businesses. Photo by Deborah Fisher.

Editor’s Note

___

Rick Lowe, best known for Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas, co-initiated the Victoria Square Project (VSP) in Athens, Greece, in 2017. VSP’s newspaper, One to One, describes it like so:

Working with various community initiatives, local businesses, institutions, the municipality, artists, and other individuals and groups, Victoria Square Project seeks to elevate the cultural and historical assets of this vital crossroads in Athens. Each participant helps us better understand the cultural, historical, and political dynamics in this area.

Jan Cohen-Cruz: Rick, where do you do your work?

Rick Lowe: I think of myself as not just a socially engaged, but a socially and community engaged artist. “Socially” alone is too broad; “community” gives it a focus. That community in my case is usually attached to a geographic context, a particular place. The kinds of issues I deal with play out through the place in which people live their lives. The work tries to create places within geographic communities where people come together to think about growth and development in their communities, that has a higher value than just surviving; rather, how they want to live in that place. Project Row Houses (PRH) has heightened people’s awareness about the context of that place and its assets, and figures out how to apply those assets there. Same with Victoria Square Project (VSP) — it provides a place that is a platform for people to think about their community’s assets and how they shape them [for that community’s good]. I think of these projects as nerve centers of their communities, bringing people together to be thoughtful.

Aerial view of “Project Row Houses” during Round 41. Photo by Peter Molick.

Jan: How do you situate your work vis-a-vis creative placemaking?

Rick: That term is a little tricky because I like to think of places making themselves and the people there having the creativity within themselves to continue to make the places they are already making. It’s not bringing anything there but rather elevating people’s capacity to continue to do what they’re already doing, making their place. Creative placemaking sometimes elevates the role of the outsider coming in to make it happen. It’s a subtle difference to place myself to honor the placemaking that’s already happening and the creative capacity already there. I work lightly within those communities to add a little focus on capacity.

Jan: Such as?

Rick: When I first went to the Victoria Square neighborhood, I met a group of immigrant women who had founded the Melissa Network, an organization to support other immigrant women and later, also refugees. I was drawn there because of the placemaking these women were already doing. I don’t go places where I’d have to bring placemaking. Once there, understanding how people are doing it, I try to add to it. There’s great work, great sensibilities, in Victoria Square, but I did see something I could bring. They were focusing mainly on immigrants and refugees, and I saw a tension with Greek natives so that’s the subtle difference — to bring native Athenians into this dialogue about how to deal with the circumstances of all these new refugees and immigrants coming into the city.

Courtesy of the VSP team.

One of VSP’s goals has been to pull people together and focus on things I’ve had experience with that help sustain communities. One is getting to know the community, understanding its assets and challenges and leveraging them in conversations with policy makers and others who will impact neighborhood development. The richness of participation we’ve garnered has gathered a lot of attention. We recently brought architects, writers, and planners together who have not been part of the public conversation and live right on our street, Elpidos [which translates as “hope”]. Twenty-eight professionals worked together, seven hours a day, seven days a week, on a mapping project to help rebuild neighborhood assets and learn how people feel about this place. Now we’re trying to distill that information, put it in a form, and get it out. Organizations and politicians are reaching out to us. ActionAid, a non-governmental development organization working in 45 countries including Greece, founded by Alexandra Mitsotakis, daughter of a former prime minister of Greece, is setting up a small office in our space, to make deeper local connections.

The current mayor announced his re-election at VSP to show he’s interested in bringing people together — that’s the future of Athens. Alexandra’s brother who is the leader of the conservative party in Greece and projected to be the next prime minister attended one of VSP’s events. They understand our overall message: you can have a culturally diverse city, but you have to show respect and encourage that diversity to be a part of the city. Valuing diversity is needed throughout the city, appreciating what refugees and immigrants can bring, and VSP is becoming symbolic of that.

Jan: Where does art fit in VSP?

Rick: First, it’s interesting that VSP came out of documenta 14, an exhibition that happens every five years, usually in Kassel, Germany. In 2017, the director split the exhibition between Kassel and Athens, and requested artists to do projects and exhibitions in both. Being a part of documenta was a sign [of recognition] from an art world perspective about [the value of] someone like me, who does not work within a traditional art framework. Having me in a major international venue helps the field, and creates more opportunities for artists like me, and for me. But projects that start with large-scale institutional support have their own challenges. There are grand expectations, and just because the project is associated with a large-scale institution doesn’t mean it’s getting large-scale support. And you have to carry the weight of that institution even as projects like this have to be nimble.

I started the research for the project for documenta in 2016, a year before the opening date. For me, research and implementation merge at a certain point. VSP kicked off publicly for the community in January 2017, but its documenta opening was not until April 2017, with a three-month “run.” I realized that the project opened up opportunities it couldn’t attain in that timeframe. It clearly had to continue beyond documenta, and here it is summer 2018, and the project is still going, seeking non-profit status to raise money.

Second, I try not to put art in this mystical place that’s beyond other activities. People come together around sports events and all kinds of things. On one hand, VSP is much like any community development work. On the other hand, like most art, it has a lot to do with intention. Which means the practical outcomes are important but the symbolic things are more important, what you are trying to explore beyond the practical. VSP’s practical outcome is to have a policy that integrates new people with existing folks. That can be reached in different ways. My concern [as an artist] is what’s deeper than the practical outcome: are people empowered, and do they see their own voice in this thing? Is there a poetic relationship that adds value for people there, not just an outcome from the mayor’s office?

At VSP, this happens through many projects. For example, we bring African drumming into the neighborhood, which causes some contention. It’s loud; some like it, some don’t. But the next day we have a Greek poetry reading maybe, and have someone bring up the African drumming in that context. There’s a conversation. People aren’t left in their separate experience of what it means to them but understand it in a community context. They leave with something deeper than if they just went for a practical end, say outlawing African drumming, which would not have led to a deeper understanding of what African drumming is.

Civic actions, like changing the name of a street, don’t have to be art projects. But if artists are doing it, they try to create some symbolic residue that will create an experience of the street name so people carry it much deeper. In our Project Row Houses neighborhood [in Houston, TX], a street name was changed from a confederate soldier to Emancipation Street, after a local park. It was not an art project, there’s no poetic residue behind it. No one understands the poetry around changing that name. That’s lost now. If we were changing a street name as an art project, there’d have been a focus on generating things of symbolic value. It could have been a musician making a song about it that came out of the process of organizing. If the story of the street is not told it gets lost, it’s just a bureaucratic function of changing a street name. Stories can be told in many ways, not just in traditional art forms like songs or murals. Art projects tease out a higher value beyond a practical function through somehow telling the story in a way that lingers.