GAC publicly puts on trial Emilio Massera, a leader of the military junta, in the retirement courts of Comodoro Py in the Buenos Aires Province with road signs that read, “Justice and Punishment.” March 19, 1998. Photo courtesy of the Grupo de Arte Callejero Archive.

Editor’s Note

__

Argentine President Isabel Perón was overthrown in 1976 in a right-wing coup d’état and replaced by a military junta. From 1976 to 1983, the right-wing, paramilitary death squad Triple A (Alianza Anticomunista Argentina, the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance) “disappeared” thousands of men and women. With support from the Argentine military dictatorship, Triple A persecuted a wide variety of leftist groups, political dissidents, and their sympathizers, and became a part of the deadly state apparatus under the first military junta, led by Jorge Rafael Videla.

The disappeared were often taken from their homes, held without legal recourse, detained, tortured, and assassinated—all without their families and communities’ ability to account for their absence or any grave that marked their death. The term desaparecido was coined to describe this particular phenomenon of political persecution experienced during the dictatorship. Marking the end of the junta, in October 1983, Raúl Alfonsín was elected the President of Argentina and during his term established the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons to investigate the crimes committed by the military.

This excerpt was reprinted with permission from the book Grupo de Arte Callejero: Thoughts, Practices, and Actions (Common Notions, October 2019), which was first published in Spanish in 2009. This version was translated by Mareada Rosa Translation Collective.

The Escraches: A Brief History

The first escraches in Argentina were realized by the group H.I.J.O.S.,1 which emerged in 1995 out of the need to denounce the impunity of institutional justice, namely the passage of the laws Obediencia Debida and Punto Final,2 as well as the presidential pardons.

The word escrache signifies in Argentine [slang] “to bring into the light something hidden” or “to reveal what power hides”: the fact that our society lives with murderers, torturers, and the kidnappers, who until this moment, lived their lives in a comfortable anonymity.

[…]

At first, the escraches consisted of interrupting the workplaces or homes of a genocidist linked to the dictatorship. Highly visible figures, such as Astiz, Martínez de Hoz, Videla, and Massera, were chosen as paradigms of the repression. It was necessary to appear in the media, so strategic dates were chosen. The objective was to put the issue on the map, and we worked to spread the action in both the neighborhood of the escrache as well as in the city center. The idea was for people to repudiate the genocidists still on the loose, to create “social condemnation,” and to question the absence of a legal punishment. The slogan became: “If there is not justice, there is escrache.” (“Si no hay justicia hay escrache.”)

[…]

Si no hay justicia hay escrache. / If there is not justice, there is escrache.

The objective was not simply the number of people who joined the march of the escrache, but rather to favor construction in the neighborhood through preliminary activities in that space, respecting its singularity, its tempos, and its subject matter. Beginning in 2001, the Mesa de Escrache Popular went into neighborhoods and began to build relationships with different social organizations, cultural centers, musical groups, student centers, and assemblies. Film series, talks, activities in schools and plazas, and open radio all took place. There was a strong sense that the escrache was a form of justice that broke with the representations of institutional justice: a justice constructed by people in the day to day via the repudiation of the genocidist in the neighborhood, the reappropriation of politics, and the reflection of the subject matter of the present.

Starting in 2003, a new set of figures began to be escrached: those who were complicit with the dictatorship and who continued to be professionally active. It began with the escrache against Héctor Vidal, a kidnapper of babies born in captivity and a falsifier of birth certificates, who was living freely thanks to the laws of Obediencia Debida and Punto Final. Six months after the escrache, his medical license was revoked. In 2004, the priest Hugo Mario Bellavigna was escrached; he was the leader of the church of Santa Inés Virgen y Mártir, worked as a chaplain in the women’s prison Devoto between 1978 and 1982, and was a member of the Comisión Interdisciplinaria para la Recuperabilidad de las Detenidas (Interdisciplinary Commission for the Rehabilitation of the Detained) where prisoners were tortured and manipulated. In 2005, it was police captain Ernesto Sergio Weber’s turn. He participated in different repressive acts during the democratic period, among them the repression that occurred directly outside the Legislature after the vote approving the Código Contravencional (Criminal Code); he was also responsible for the deaths during the repression in Buenos Aires on December 20, 2001.

“If there is not justice, there is escrache.” GAC’s first mobile escrache travels past the homes of various genociders of the military dictatorship. December 11, 1999. Photo courtesy of the Grupo de Arte Callejero Archive.

Thinking Work in the Neighborhoods

The Mesa de Escrache works from an idea of equality. Its practice aims at social condemnation, which asks for the participation of society in general, and is oriented towards an encounter between emotion and the desire for a just society. Its organizational structure is reflected in each weekly meeting, where opinions are exchanged and decisions are made via consensus, with a clear tendency towards horizontality. In this sense, the working group distances itself from every idea of political practice as that of individual actors, where in an action some have more rights than others, or whose actions serve to create a spectacle of individual pain. As Alain Badiou notes, no politics will be just if the body is separated from the idea, even less if it is realized as a spectacle of the victim, since “no victim can be reduced to their suffering, within the victim it is humanity as a whole who is beaten.”3

For this reason, the practice of the escrache centers on living memory, which creates and acts, generating political practices by means of joy, celebration, and reflection. It moves away from the practices of judicial power, which reify and individualize social problems, and which generate a spectacle represented in the practice of justice.

[…]

The process of the escrache interrupts everyday life in the neighborhood. Having picked a target, the Mesa de Escrache Popular moves into the neighborhood where the genocidist lives. Its arrival produces worry and curiosity, since every weekend the neighbors see a group of people handing out info sheets explaining the criminal record of the next target of the next escrache and inviting them to participate in the working group. The group meets in a public space, which means that over time the neighbors get to know the members and know why they are there. The answers of the neighbors are varied and imply distinct levels of participation. We understand participation in a broad sense, as the act of communicating events, for example, when a neighbor rings another neighbor’s doorbell to tell her that a genocidist lives next door. Another example would be the information these same neighbors offer about the everyday practices of the genocidist (“He gets his hair cut there;” “He eats breakfast every day at such and such an hour in this bar;” “He is friends with this guy,” etc.).

The practice of the escrache centers on living memory, which creates and acts, generating political practices by means of joy, celebration, and reflection.

The practice of the escrache generates multiple interventions, including those by the family members, friends, and institutions that defend the genocidist. There is, for example, a constant tearing down of the posters with the genocidist’s photograph, as well as telephone threats, accusations of defamation, and, in some cases, police persecution to intimidate and seize the belongings of those participating in the escrache.

Day by day in the neighborhood, the practice of the escrache constructs images that mark the genocidist, removing him from his everyday anonymity. The walls begin to say, “There is a torturer in this neighborhood” and “If there is no justice, there is escrache.” The neighbors are now on alert, receiving flyers and dialoguing with the participants in the escrache. The aesthetics of the neighborhood change, symbolically cornering the genocidist: no neighbor can ignore what is occurring because when they leave the house there is a poster on an otherwise abandoned wall; when they go to the store, there is a map clearly marking the home of the genocidist; when they throw a piece of paper into a public trash bin, there is already a sticker on the bin denouncing the genocidist; when they stroll through the neighborhood on the weekend, they confront a group of people discussing and denouncing genocidal practices. In this way, the landscape of the neighborhood changes, giving expression to a social problem that invades the furthest corners of the neighborhood.

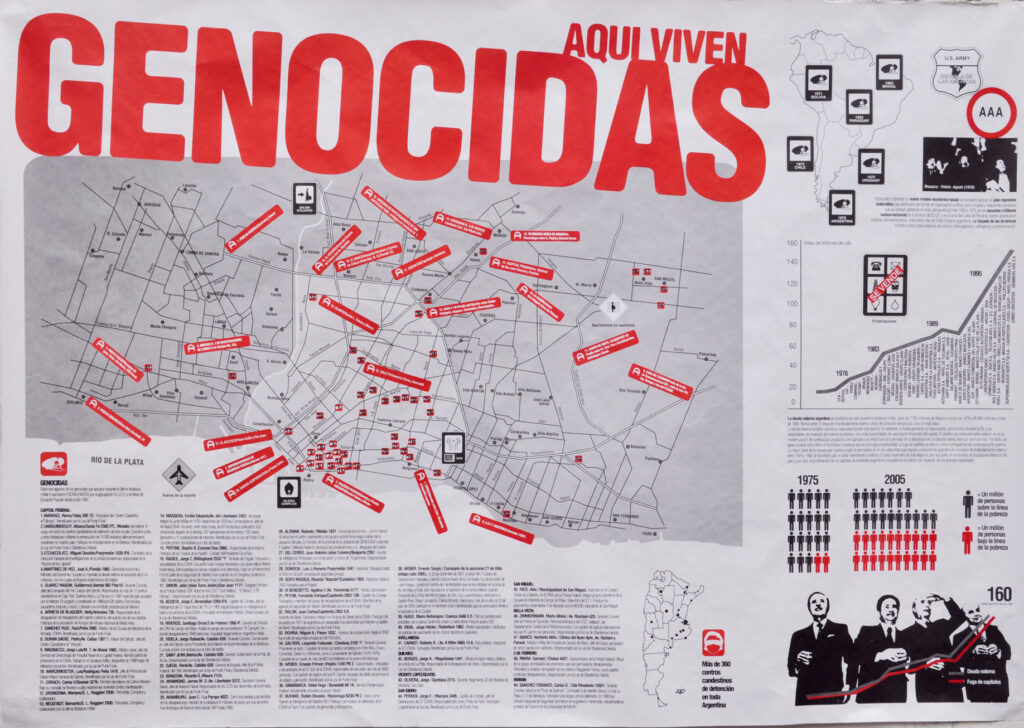

A “Genociders Live Here“ poster showing the addresses of those complicit with the 1976-1983 dictatorship. The poster was updated annually from 2002 to 2006. March 24, 2003. Photo courtesy of the Grupo de Arte Callejero Archive.

While it is very important to do the escrache against the genocidist, at the same time the escrache is an excuse to come to a neighborhood and take on the problems of the present. From this place, we have worked together with neighbors on problems of housing, police violence, corruption in the courts, the fear of talking about the past, creating spaces of encounter, and reflection that relate the genocide to new problems.

[…]

Once it is time to move to other neighborhoods, actors in the group and those in the neighborhood will continue to discuss what occurred in this shared lived experience.

In this sense, we can understand the practice of the escrache as a possibility of opening a process of political subjectivity, as it is defined by [philosopher Jacques] Rancière: “An enactment of equality—the handling of a wrong—by people who are together to the extent that they are between.”4

Escrache: The Use of the Image

[…]

In the beginning, [Grupo de Arte Callejero was] participating from a slightly external position: accompanying the process. Afterwards, we contributed and involved ourselves more. Our participation was further increased when the activity of the escrache opened up completely and Mesa de Escrache Popular was created. As such, the demands made visible by the family members who were accompanied by others broadened and created a very powerful political position, totally different from the forms or traditional spaces belonging to parties or unions. At that time, we felt the need to mark and signal the spaces in the city that had served as CCDs (clandestine detention centers), thinking of the nonvisibility of those spaces and the ways in which they were or were not recognized by people passing by. We proposed working on the physical spaces of state terrorism and their invisibility with the objective of unveiling the subjects (by means of an escrache) who participated in the dictatorship. We took into account that the majority of the CCDs were not built specifically to be used for the dictatorship, but rather that commissaries, military offices, and public buildings were recycled for the purposes of repression and extermination. For this very reason, in order to signal these spaces and make them visible, the experience of the escrache was helpful.

[…]

A “Genociders Live Here“ poster showing the addresses of those complicit with the 1976-1983 dictatorship. The poster was updated annually from 2002 to 2006. March 24, 2006. Photo courtesy of the Grupo de Arte Callejero Archive.

Our contribution is in the thinking through and making of images in relation to the energy that working on the escrache generated. From the beginning, we chose to use the aesthetic of signage, using mock street signs (made of wood painted with acrylics, printed using silk screens or stencils), to subvert the real codes: maintaining colors and icons but completely changing their meaning. The space being used is the same as the real spaces in the city: on the posts that one finds on the street. We sought to place the signs in spaces that were amply visible both to the passerby and to the driver. These signs served as a spatial intervention in the city, losing and discovering themselves in the daily visual pollution, managing to infiltrate the framework of the city itself.

The great transformation that was implied for us in thinking of the image in the escrache concerned, on the one hand, language: the idea of tweaking a determined code (urban street signs). On the other hand, it was the idea of a temporal event that was repeated as a carnivalesque interruption of which the signs were the trace, that which remained “after.” The temporality of the escrache made possible the emergence of a type of serial image that reappeared each time. Besides marking the path, the signs mark a time, intervals of time, between escrache and non-escrache, and also between the escrache and other spaces where the same signs appeared copied by other groups. Perhaps for this reason we can consider all of the projects where signs were deployed as a large conceptual unit that spans from the group’s beginning to the present day.

Walking Justice

[…]

With the arrival of the government of Kirchner and, in June 2005, the annulment of the Obediencia Debida and Punto Final laws, a new moment emerged in the prosecutions of the dictatorship and with this, a shift in position regarding social organizations and movements. The question was raised: with these new trials, would the escraches end? Our thinking was that the practice of the Mesa was a kind of social work, starting from thinking of the genocide not as an individual condition but as a collective one. The answer then was that in the best of all possible outcomes, if all the military repressors were put in prison, the process of the escrache would still continue, because its principal objective was to reflect on the social transformations and the rupture of the network of intersubjective relations produced by the genocide in order to also address current social conflicts. In this way, an idea of justice that distances itself from the logic of institutional justice began to be formed.

[…]

An idea of justice that distances itself from the logic of institutional justice

This was an attempt to construct a social condemnation seeking the production of justice outside of institutions and constituted within the day-to-day life of the neighborhood via a process of reflecting on the past and present. The neighbors choose to not have genocidists as neighbors, and they demonstrated their repudiation of them. For example: after meetings of the working group in a particular neighborhood and after the march of the escrache, a building association got together and asked the genocidist to move somewhere else because they didn’t want to live with him any longer.

[…]

This is how the Mesa proposes to transform vis-à-vis a “walking justice,” one connected to a knowledge of the past, which is considered along with the present. A walking of everyday justice, neither programmatic nor future-orientated, coinciding with Badiou’s notion that justice is the name of the capacity of bodies to carry ideas in the struggle against modern slavery, “to pass from the state of the victim to one who stands up.” Justice is a transformation: it is a collective present of a subjective transformation, as a process of construction of a new body fighting against the social alienation of present-day capitalism.

Grupo de Arte Callejero (GAC) is currently made up of Lorena Bossi, Carolina Golder, Mariana Corral, Vanesa Bossi and Fernanda Carrizo, who all live and work in Buenos Aires. The group was formed in 1997 in Buenos Aires, by a small group of Fine Arts students. Their first interventions ranged from mural-graffiti to actions on advertising posters. In 1998, they began participating in the escraches of the group H.I.J.O.S., creating a type of public complaint signage in the form of mock street signs. In 1999, they won a sculpture competition for the city’s Remembrance Park with their work Posters of Memory, which remains in the park today. The formats chosen for their interventions include installation, graphics, performance and video. They have worked collaboratively with human rights organizations, independent unions, non-partisan political groups, organizations serving the unemployed, and research groups in various areas of culture. In 2009, they published the book Thoughts, Practices and Actions of the GAC, Ed. Tinta Limón. http://archive.org/details/GacPensamientosPracticasYAcciones

Notes

1. The organization H.I.J.O.S. stands for Hijos e Hijas por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio (Children for Identity and Justice against Oblivion and Silence) and comprised of advocates and the desaparecidos’ children, many of whom were kidnapped by members of the Argentine military and then raised by other families.

2. Passed under President Raúl Alfonsín, the two laws prevented the prosecution of the perpetrators of state violence during the 1976–1983 military dictatorship. Obediencia Debida stated that members of the military below colonel rank were exempt from prosecution because they were following orders. Punto Final set a very short statute of limitations for prosecutions of crimes. Both laws were ultimately overturned.

3. Badiou, Alain, “The Idea of Justice,” conference presentation given on June 2, 2004, in the Facultad de Humanidades y Artes in Rosario, Argentina.

4. Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), p. 61.