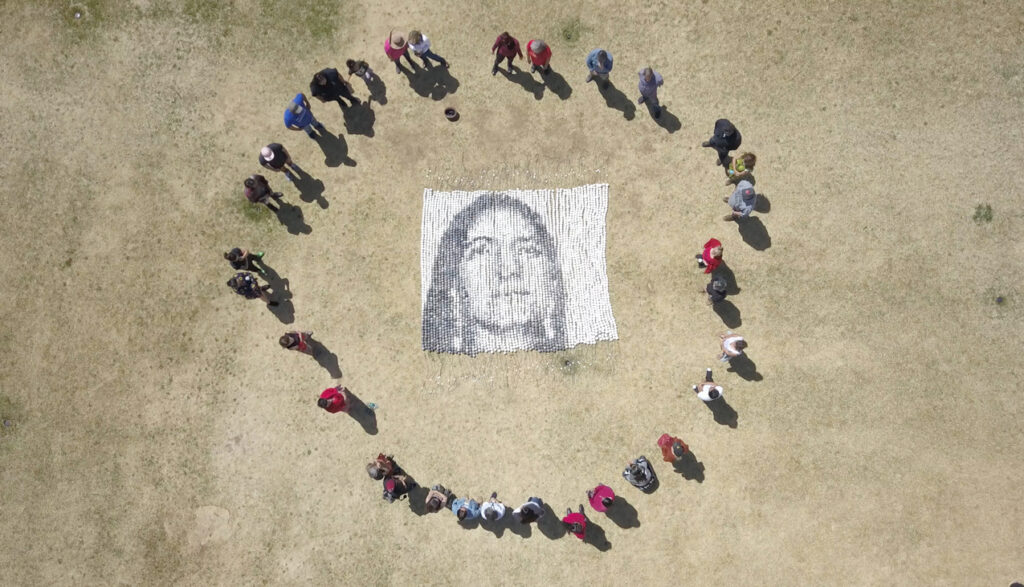

Mirror Shield Project at Oceti Sakowin camp, Standing Rock, ND 2016. Concept artist, Cannupa Hanska Luger, with drone operation and performance organization by Rory Wakemup. Image courtesy of the artist. The artist thanks Jack Becker from Forecast Public Art for helping bring Mirror Shields to Standing Rock and Rory Wakemup at All My Relations Arts in Minneapolis, MN, who facilitated a workshop, hosting Luger as guest artist for the Mirror Shield Project.

Editor’s Note

__

Settlement is a radical performative encampment conceived of by contemporary artist Cannupa Hanska Luger, in which Indigenous artists from across North America and the Pacific were invited to occupy Plymouth’s Central Park in the United Kingdom for four weeks in fall 2020. Settlement is a key Indigenous-led aspect of the Mayflower 400, a year-long multi-national cultural program that commemorates the 1620 voyage of the pilgrims to the “New World.” The project aims to go beyond conversations around decolonization and actively practice Indigenization. We spoke to the artist to understand how it supports the descendants of the settlers in moving towards a more relational understanding and acknowledgement of contemporary Indigeneity.

PRERANA REDDY: I wanted to start with just a little bit of background about your art practice. You have previously mentioned the concept of individuality as being central to a Western way of thinking and commodification. I know your practice has increasingly moved from individual to collaborative, with other artists such as for Settlement, but also sometimes collaborative with movements.

CANNUPA HANSKA LUGER: What really started to push me out of being just a studio practice artist was the water protectors gathering up at Standing Rock during [the movement against the] Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016. I’m from Standing Rock. As it was coming through, it was drawing oil from the Reservation that I am enrolled on. It was all so close to home, and so I felt compelled to activate how I was able. I recognize that I have privilege as an artist: I have access to institutions, media sources, and influence with the larger public. Out of pure desperation, I came up with the Mirror Shield Project, to make something to protect the water protectors on the front line. Going to the camps several times to deliver supplies and offer support, I witnessed the extreme brutality taking place. I wanted to create some form of protection that was also reflective, for the police to witness themselves, and to assert the notion that we were protecting the water for everybody—including them.

For the Mirror Shield Project, I used social media as a platform or call to action in order for the public to create the shields, and it changed something in my head. Honestly, I never really looked at social media much before, I didn’t understand what its point was, but as all of this was unfolding and I saw its power to amplify voices and to share people’s situations, it became a profound resource. That river is wide and shallow though, you know? What does “liking” and sharing actually do? But giving people a task, it becomes an activation. Online everybody is an ally, but not everybody knows how to be an accomplice. So if you create something you can embed into the movement, put some sweat equity into it, you shift from just an ally to an accomplice, you become invested.

I’ve done several other projects since then using that same model of large calls to action through social media. Every One (2018) was a large scale clay work representing missing and murdered Indigenous women, queer, and trans relatives, in which hundreds of communities from across the U.S. and Canada created and sent over 4,000 ceramic beads, which I then used to complete the physical work. And I currently have a project in process called Something to Hold Onto (2020), calling for over 7,000 unfired clay beads which will be strung together to create a continuous strand, representing the lives lost on ancestral migratory routes of Indigenous peoples affected by imposed borders. These works attempt to make sense out of unfathomable data, it’s an attempt to re-humanized data. Especially data that actually creates policies for change or structures of accountability.

Cannupa Hanska Luger

MMIWQT Bead Project (Everyone), 2018

Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM

Photo courtesy of the artist

And so, when I was invited to engage in a large scale project in Europe to build Settlement in Plymouth, U.K., one of the things that I wanted to dispel was the notion that Native Americans are just one people. The idea of the Native American as a singular group is inaccurate; this massive umbrella term actually represents nearly 600 diverse tribal communities, with hundreds of language groups, hundreds of different cultural practices, songs, dances, and different scientific and cosmological backgrounds. Yet under this umbrella we become homogenized under the European gaze, and to popular culture in America, we are seen as one-dimensional characters. And the only way to really learn and to grow and to appreciate Indigenous peoples is to recognize our complexity. So for Settlement, I wanted to bring together as many Indigenous artists, philosophers, and radical thinkers as I could support to be in conversation with one another, for us to contradict one another and be honest.

PRERANA: So just to step back and talk about Mayflower 400, this multi-national commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower voyage. What does that mean to Plymouth itself as the starting point of that voyage, and what does it mean to be invited as an element of that commemoration? How did that invitation come to you?

CANNUPA: A group from Plymouth, U.K. called The Consciousness Sisters reached out to me and asked if I would be interested in doing something contemporary in relationship to the Mayflower 400, where a lot of the programming being developed was commemorating historical events. I was like, “No, I don’t think so. Why are you asking me?” See the Pilgrims never made it to my people of the Plains region. There is no ocean where I’m from, you know. We weren’t engaging with the West until the 1800s.

Then I started thinking about the effect of how the only representation of Native people is so often us in buckskins and feathers—as historical. Almost every time I’ve gone to Europe, somebody has said, “You don’t look Native American to me.” And I’m like, “I’m not. There is no such thing.” So I decided to work on the project in order to create something hyper-contemporary, to show us as we are: complicated, complex, intelligent, and hard to perish. Building a settlement on the grounds of Plymouth’s Central Park and doing an Indigenous creative occupation would be a great opportunity to flip the narrative of the Mayflower 400 program. Rather than commemorating 400 years of colonialism, we would acknowledge how those first efforts affected tribal communities across all of America and into the Pacific. The Wampanoag [on whose territory the Pilgrims landed] already had representation [in this commemoration] as one of the host nations for the Mayflower 400, so with Settlement I wanted to bring the varied contemporary stories of Indigenous peoples within that 400 year period who were also deeply affected by colonization and who continue to also thrive despite. Ginger Dunnill, the U.S. producer of the project, and I started to look for artists, and we ended up with 28! Everyone was really excited to show the complexity and the contradictions of thought, philosophy, song, dance, and then to produce work together through a contemporary lens.

Almost every time I’ve gone to Europe, somebody has said, ‘You don’t look Native American to me.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m not. There is no such thing.’

PRERANA: One of the other things that was interesting to me was the process of that collaboration. How you all decided collectively what to do, and maintain a certain kind of individual sense of your own work but also, how are all these things fitting together; how are people working together?

CANNUPA: Yes, this project challenges Western ways of thinking and organizing that we are subject to all the time as artists. We wanted to develop programming through consensus rather than a curator or lead artist telling everybody what they should and shouldn’t do. It takes longer to do this process than to simply dictate to somebody what they should do. I kept telling all of the artists, “Look, the fact that we’re going and doing this at all is amazing. That’s the work. What we present, that’s all bonus, that’s cream.” That kind of alleviated any sort of pressure on each artist to be performative—showing up and witnessing each other, was the real work.

And now that this global pandemic is a part of our piece, there’s something ironic about it all, as far as how Native people and pandemics go. Like how come it’s always got to be a bug!

PRERANA: This was supposed to happen in person in July and August 2020 and before we go into how that changed, I wanted to touch upon another thing, which was the community engagement piece. There were meant to be local engagements outside of the encampment itself, right?

Pounds House, a historical mansion in Plymouth, UK, was planned to be the physical site of activation for Settlement. Image courtesy of Fiona Evans, Settlement UK producer.

CANNUPA: What was really interesting about working in Plymouth, is the fact that Plymouthians do not care about the pilgrims. Pilgrims were the people that they asked to leave because they were so puritanical. Americans are the only ones who give a damn about the pilgrims, as their forefathers. It’s all embedded in the American mythos. Rather than bringing American tourists to Plymouth, we were bringing American artists to Plymouth to engage with Plymouthians, to engage with Europeans, to engage with the British. All the development work I had done over two years, traveling to Plymouth, engaging with different communities out there, it was just a slightly different model. This project had to be for us as Indigenous people primarily, and then whatever that experience could become onsite would be shared with the communities at large. And those from Plymouth who were interested could come and participate to create something with us as artists, rather than be voyeuristic. Let’s get engaged. The whole thing wasn’t extractive, even to the British community.

PRERANA: We talked about the high roading concept, how not to be extractive, and how not to fit into this system that stereotypes Native Americans. How do you prepare to be in this moment of commemoration around people who may or may not acknowledge that history in the same way? And how do you prepare for both the potential for trauma and the potential for healing around the fact that you will be having agency in that space?

CANNUPA: There’s a growing understanding of the negative impacts of settler colonialism around the globe, and the lasting toxic effects of colonialism socially. But the understanding of extractive colonialism, the removal of resources, that’s not as openly and commonly understood. With Settlement, we have been dealing with the U.K. in the middle of Brexit. That effort to try to close its borders to outside places. Ironically, Plymouth itself is a city that almost every single settler colonial and extractive colonial voyage from the U.K. took off from. The boats were all built there, and that’s where everybody stopped before they headed out into the world.

Simultaneously, looking at the Welsh, looking at the Celts, looking at the original inhabitants of that land, what was really triggering for me was recognizing that they have been colonized a lot longer than anybody else. It’s embedded in their history, and they don’t even recognize the toxicity of it because it’s happened for so long that it’s been perpetuated as their cultural model. And that colonization has been going on for about 5,000 years. So, how are you expected to be fully open to communication and dialogue under the weight of that trauma?

They have started doing all these projects in Plymouth to amplify their Celtic traditions, the primary people of that region. Catalyzed by the Settlement project, members of the Plymouth community have been making traditional wool fiber and other craft and researching their Indigenous plant medicines, ceremony, and regalia. They are working with students within the primary schools, learning about their place and their people and their belonging to that land from a cultural standpoint. I thought that it was really important that they get in touch with their own heritages, myths, and legends instead of exotifying the umbrella of Native American culture to fill that void. I think this all has sparked something in them as a people that could heal some deep trauma into the future.

We all have trauma and to confront it is, well, confrontational. Power is being vulnerable enough to work to heal your trauma in real time with your community, to confront it. But what I’ve experienced as a human being is that we have created a system that reinforces the idea that power equals strength. Somewhere along the line, we all decided to agree that power was strength, and that was the birth of patriarchy. If strength is power, then the male form has some sort of dominant role over everything to wield that power. But I can’t bench press a child into the world. Power is something that’s much greater than strength. And confrontation reinforces the idea of strength as power, but to nurture, and to care, and to support people through their own trauma, I think has a lot more to do with the primary powers of our world, which is creation and empathy.

Production image from artist films created for Settlement digital occupation. Participating artists Raven Chacon (left), and Nanibah Chacon (right), seen here. Image courtesy of Red Brigade Films and Razelle Benally.

PRERANA: I think the sense of generosity, and that meeting with some sort of, not necessarily equality, but meeting somewhere where you both have stakes seems to be what you were trying to build. And that is actually healing and generative. It’s not like something was done to me, and now I’m going to make you feel bad about it.

CANNUPA: Yeah, it’s more so like, something bad has happened to all of us, you know, somewhere along the ancestral lines. And we have been playing this game of telephone with that bad situation for so long that we forget that we are all deeply traumatized by it, we are all suffering from it. And even if one person is suffering, we are all suffering. I’m trying to figure out how we can make people recognize that the world is in process and that it is not a dictionary of nouns. Everything seems to be or is subject to something, but that’s not what it is—we are not those things, we are subject to situations. Even that notion of equity and equality is inherently a power dynamic: equal to what? I’m not looking for equality, I’m looking for somebody to listen, to witness, that’s it.

PRERANA: Well, with that I’m going to ask you how your plans have had to change. Traveling is not possible to Europe right now. Obviously the idea of this tourist attraction has changed, and your project is not about that aspect anyway. But what does it mean to have this not be, to the extent that you had planned, a physical manifestation? And what will it be?

I’m trying to figure out how we can make people recognize that the world is in process and that it is not a dictionary of nouns.

CANNUPA: We are moving forward with the project as a digital occupation. This October, Settlement will be going live online, and we will have the work of 28 artists indigenous to North America and the Pacific represented. The online platform will be a space for Indigenous artists to activate a creative response and claiming of digital space to consider the impacts of colonisation on a diverse number of tribal nations who continue to thrive despite its long term effects. Across the winter, the online platform will include performance, artist discussions, and social engagement opportunities. Through innovative media approaches of idea sharing, our art practices can reach an even larger global audience. This digital occupation is a space to map our stories, on our terms, in a landscape unhindered by borders. I hope this work will create a living archive for contemporary Indigenous artists and that global investors would consider hosting this project in their region. We were talking about doing it again here in Alcatraz. And have the same kind of concept and approach, but engage with our oppressor.

PRERANA: And also, it’s a reoccupation at Alcatraz at that point, right, so it connects to the whole American Indian Movement history.

CANNUPA: Yeah. And there was traction in that scenario, and it’s still a possibility. Honestly, I always thought about this Settlement project with the two definitions of settlement in mind, both the legal and the physical. To come to some sort of consensus through engagement and communication is how you come to a settlement. It’s an official agreement intended to resolve a dispute or conflict. I’m really interested in doing the project this time with the Mayflower 400 in the U.K. under the premise that this is just the first step, and it could potentially be something that is bigger than us. What if this became a model for every country around the world that’s been subject to colonialism, and settler colonialism, to create an opportunity to develop a settlement? A temporary creative occupation of the colonial landscape. And I would really be interested to see what that looked like from other cultures and other communities, and to experience that myself, as somebody outside of it. I would just love to see it from another perspective, where I’d just be like, “Oh, this is so righteous. This is a good way forward.”

Cannupa Hanska Luger is a multi-disciplinary artist of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, and European descent. Using social collaboration and in response to timely and site-specific issues, Luger produces multi-pronged projects that take many forms, provoking diverse publics to engage with Indigenous peoples and values apart from the lens of colonial social structuring. Luger lectures and participates in residencies and projects around the globe and his work is collected internationally. He is a 2020 Creative Capital Fellow, a 2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, and a recipient of the 2020 A Blade Of Grass Fellowship for Socially Engaged Art. He received a 2019 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant and was winner of the 2018 Museum of Arts and Design’s inaugural Burke Prize. See more from the artist at www.cannupahanska.com and on instagram at @cannupahanska.

Prerana Reddy is Director of Programs at A Blade of Grass. Previously she was the Director of Public Programs & Community Engagement for the Queens Museum in New York City from 2005–2018, where she organized both exhibition-related and community-based programs as well as public art commissions. In addition, she oversaw a cultural organizing initiative for Corona, Queens residents that resulted in the creation and ongoing programming of a public plaza and a popular education center for new immigrants. She is currently on the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs Advisory Commission and sits on the boards of NOCD-NY, ArtBuilt, Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability & Equity, and New Immigrant Community Empowerment.

Settlement, an Indigenous Digital Occupation, will premiere October 13th, 2020, at www.sttlmnt.org

Follow the project on instagram at @settlement_uk