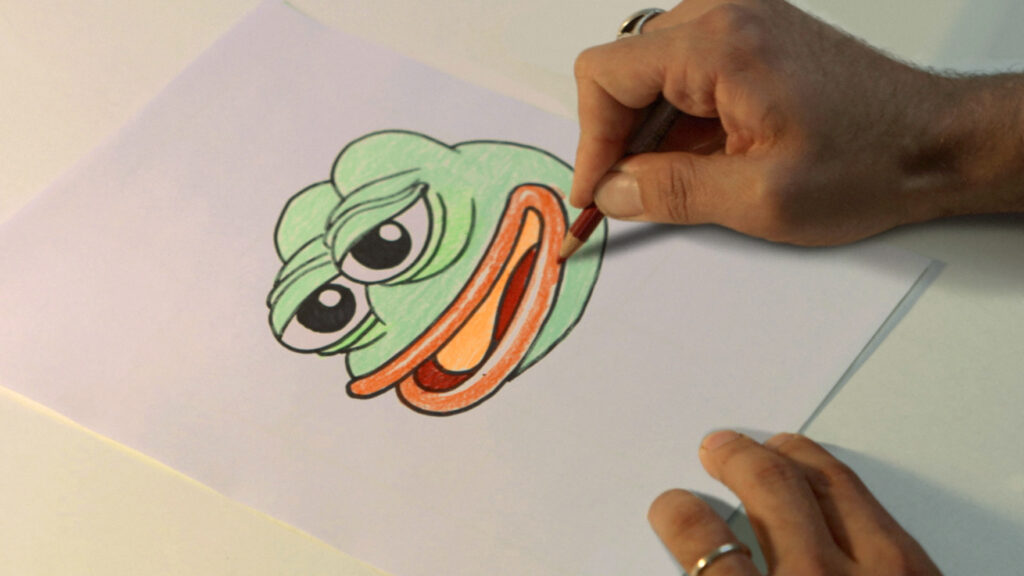

Illustration by Matt Furie, courtesy of Arthur Jones.

Editor’s Note

__

Pepe The Frog entered mainstream society on the tidal wave of white cultural backlash that President Trump rode in on, a seemingly out-of-nowhere icon: a cartoon frog that inexplicably embodied fascistic tendencies and an “America First” ethos, communicated solely through his bulging, squinty eyes and noncommittal sneer. At that point, Pepe was a long way from his Boys Club home, a humorous and popular series created by underground comic artist Matt Furie in 2006, and only halfway on his journey that would span the entire world and political spectrum. In 2017, artist and art director Arthur Jones began directing his first film, Feels Good Man, documenting Furie’s efforts to challenge the gambit of white supremacists, self-marginalized male youth, and MAGA enforcers who populated the 4Chan communities where Pepe became radicalized; claiming for themselves the artist’s sweet, selfish, stoned frog.

Over the 2020 summer, with now incumbent President Trump only intensifying what has been his four-year run for reelection on a white supremacist platform, journalist and filmmaker Michael Premo interviewed Jones by video call to discuss the serious socio-political implications of the rightwing media tactics that have been naively dismissed as “trolling,” and the ethical and aesthetic implications of documenting the culture on film right now. Feels Good Man will be featured in the season premiere of Independent Lens on PBS, October 19th, and can be rented on all major streaming platforms.

MICHAEL PREMO: Congratulations on the film. I’m curious, before you even thought about doing this film, what kind of work were you doing? How did it lead you to making a film on this topic?

ARTHUR JONES: This is my first film, and I never really thought about myself as a documentary filmmaker before. I never really wanted to make work that was socially conscious, honestly. Mostly, I would make money doing advertising, doing marketing, that kind of stuff, as a freelancer. But [this] subject matter was something that I became really obsessed with. I was friends with Matt Furie, who’s the subject of Feels Good Man, through the indie comics world.

Then I started to see Pepe the Frog pop up online. In 2015, there was this two-week period where Pepe the Frog was supposedly used by a school shooter in Oregon on October 1, and then two weeks later then presidential candidate Donald Trump retweeted an image of Pepe as himself. And I was like, “What do they have to do with my friend’s comic?” That was the inciting incident for me as an artist.

MICHAEL: So, what was in the air and the context of you growing up? Were you pre-social media? Seeing these memes, was that sort of new for you? Or was this something that you had grown up with?

ARTHUR: This story really appealed to all the things that I was personally obsessed with: underground and independent comics, but also conservatism in America. I was raised in an evangelical family in rural Missouri. I definitely recognize a lot of the reactionary politics of the right from stuff that came from my upbringing. If 4chan had been around when I was in high school, I might have been a kid on it. I know what it’s like to sort of come out of the fog of right-wing media and basically feel as though you have to… almost escape a cult. As I was making the film, I thought, “If I was seventeen years old and watching this, what would I think about it at this moment?”

I also felt like it was important to really address the cynicism of what’s going on right now. A lot of films about social media don’t really engage the subject matter in an emotional way. This film really allows you to talk about the way emotion spreads in groups online, how it can kind of metastasize, and how it can be coalition-building. I think most people’s politics are based on sort of a personal emotionality. I also thought it was a unique chance to make a film that people on both sides of the cultural divide would view and have different thoughts about.

MICHAEL: I’m curious if you could say more about what your upbringing means and how that might have also influenced how you structured and approached making the film.

ARTHUR: The things in 4chan that I recognized in myself as a teenager was this sense of self-righteousness. I really had this sense that the whole world was against me, and I feel that’s the kernel for a lot of people on 4chan. They feel trapped in this echo chamber. It’s a platform, but it really becomes a mindset. But 4chan is also a place where people post pretty unvarnished stories, and so they are kind of open to you being open with them. So, I took a journalistic perspective of being a little bit more immersive. And that does create problems because sometimes you are being immersive with people whose viewpoints you realize are more extreme than you initially thought when you first started talking to them. We had to figure out what are the guardrails, so that these subjects aren’t necessarily taking control of our narrative, and we weren’t putting forth this toxicity into the world in an irresponsible manner.

MICHAEL: That’s exactly what I’m curious about. What were some of those guardrails? How did you help deal with that?

ARTHUR: We wanted to find really powerful voices that push back, to always make it feel like the adults were in the room. So, we got great voices like Adam Serwer who writes for The Atlantic. We got great voices like Aaron Sankin, who is someone that I knew from the world of The Center for Investigative Reporting. We wanted to make sure that everything was contextualized.

MICHAEL: Did you ever try to reach out to any people who are self-identified white nationalists?

ARTHUR: In the very beginning of this project, I did think about reaching out to some white nationalists, and I did have phone calls with some guys that were straight-up self-identified fascists. But I very quickly realized that wasn’t going to be responsible or productive. I think you saw, post-Charlottesville, a different dialogue happening within documentarians and journalists about what is responsible to show and what is not. Filmmaking is a visual medium and you really have to be aware of the potency of the images you are putting forth. People like Richard Spencer know exactly what they are doing in terms of the way they address the media. Those guys spent enough time in the 2015-2016 moment on network TV, in major publications. We could very easily take the things that we needed from those sources.

Artist Matt Furie drawing Pepe in the film Feels Good Man. Photo by Kurt Keppeler.

You will notice in the film that you never hear Trump’s voice, and there’s a lot of pretty toxic, racist, fucked up memes in the film, but we chose to omit animating those because it just had too much stage presence. We really wanted the film to take Matt’s initial intention of the character of Pepe the Frog and canonize that. There’s a lot of copyrighted characters that are used by racists online. SpongeBob SquarePants is a really popular racist meme, but it has a huge corporation that is able to protect that intellectual property. Matt didn’t really have those sorts of resources at his disposal, so we really sought to canonize the version of Matt’s character that felt true to Matt and those original comics.

MICHAEL: It’s really great to hear the sort of thought process that went into that decision, particularly around how to canonize the original intent. I’m really curious if the film presents an opportunity for folks to understand the right or the left in any kind of way?

ARTHUR: We are dealing with a situation where the Internet is basically commodifying our emotions. All of our likes and dislikes and comments are now being collected and aggregated and used to sell us shit. Pepe is part of the same attention economy, but on places like 4chan it is an attention economy of extremism, where the only way that you are able to gain status in that community is to be edgier, and shitter, and more cynical, and darker, and more fucked up than the other person, and that ultimately leads to fascistic thought. And they can pretend like it’s a bunch of jokes, but the reality is that these ideas trickle up from these rather niche platforms into mainstream discourse. Like it or not, the future of our democracy is going to be in the comment section of YouTube. I do think one of the reasons Trump got elected is because we all got our grandparents on Facebook, and they just didn’t know how to understand all the shit being thrown at them. I think as we move forward culturally, we really have to have more of an incisive understanding of the way in which we communicate.

We are dealing with a situation where the Internet is basically commodifying our emotions.

MICHAEL: Did you personally learn anything new or make any discoveries about the mechanics of right-wing, or left-wing, politicization in this process?

ARTHUR: In one scene in the film, we talk to a consortium of computer scientists who have basically been collecting every single post on 4chan and every single post on the politics board of 8chan before it disappeared. Those guys trace how a lot of the ideas that end up in more mainstream sources like Fox News or Donald Trump’s Twitter feed start in these online fever swamps. We certainly see that playing out also in the way the primaries have been moving in America. If you read Ratf**ked, that book about gerrymandering in America, you know that gerrymandered districts have a bunch of like-minded people; the voices that end up winning in those blocks are the most flashy and extreme voices. You end up getting the most extreme voices coming out of these primaries, and then those people are ending up in Congress. [As I was] finding people to talk to when I first started the project, there was a sense among very lefty academics that this is something that we can’t give too much credence to or is something that we can’t talk about really.

MICHAEL: What exactly is something we can’t talk about?

ARTHUR: Well, it goes back to the question, were we going to talk to white supremacists in the film or not? There was this appeal that you can’t give it oxygen, but I think not giving it oxygen basically allowed all of these right-wing ideas to have potency within culture. We have to be able to talk about these things, address them head on and be able to call things crazy or fascistic for what they are.

The argument about 4chan and the 2016 election is that the constituency of people that were on these message boards didn’t necessarily translate to voters. It’s a young group of people that weren’t considered to be part of the process. But I do think they are basically the people who are controlling the discourse. We really have to understand that dynamic.

Like it or not, the future of our democracy is going to be in the comment section of YouTube

MICHAEL: To bring it back to this question of art, there’s a school of thought that would argue that all art is political—even your apolitical stance is a statement of politics. Would you say that the dilemma of Matt and Pepe the Frog makes you for or against that particular statement?

ARTHUR: With a certain sort of intellectual imagination, you could say Pepe is an emblem for capitalism. So much of the left versus the right [discourse] is choosing to ignore the systems that we all live with and the systems that control us as a society. And certainly, all art gets made within a context, and therefore I think all art comes from a certain time and a certain place, and is able to tell us something about ourselves that we didn’t necessarily know before. That was one of the things that certainly fascinated me with this story.

The dialogue around Matt is also fascinating because it’s totally new. It’s easy for people to be critical of Matt but the reality is this has never happened before—it’s a totally unique situation. It’s something that I think is going to be looked back at with a lot of interest and scrutiny. I think as the Internet becomes a more potent force in our lives, art and the things that we make are going to become more important just because more people are making stuff all of the time.

The Trump surrogate in the film, Matthew Brainard, talks about how memes basically energize a group of supporters because they feel like they are now part of a campaign. MAGA became a people’s movement because people were making media, and then that media was getting adopted by the figureheads of that movement. I do think art and artmaking is going to shift into being more political as more things go online. Because the way that we basically build community is through these memes that we are making, the things that we are sharing on our phones, the things that we are selling on Instagram, Etsy, and all this sort of stuff, in order to make it in the gig economy. I think art is becoming commerce faster and faster, and being aggregated for data mining purposes. I’m curious to see if there will ever be a way to take the best parts of social media, remove all of the data mining and privacy invasion, and create a more egalitarian artistic community.

MICHAEL: Yeah, I do feel like there is some precedent for this. If we look back at how myths and legends and stories traveled through society, they were definitely used by a wide variety of different people to communicate and express their values. We are seeing the mutation of that in the Internet age in totally crazy ways, but I think there’s something sort of an innately human about what we are experiencing that I have yet to put a finger on. I certainly appreciate your film because it’s provoked that sort of thinking for me as I was watching it.

ARTHUR: Oh, that’s great, man. It’s funny, in the film we interview a guy who’s a magician, and people either love or hate that. There’s a certain sort of documentary purist that is like, “Oh, you guys, come on.” But I mean, the film is about a cartoon frog that’s stoned. There is something about it that is impossible, there is a randomness to it that is kind of crazy and unpredictable, and there isn’t precedent for it. We need to talk about it in a way that’s going to slightly open people up to thinking about a larger way of encountering the zeitgeist. The magician is really talking about art and willpower combining into cultural moments; people imbued Pepe with significance, and then that significance took on a life of its own within a community of people.

MICHAEL: What I loved about [that interview] was its ability to speak to this ancient way that ideas move through societies. And I immediately thought of the “Kilroy Was Here” graffiti that emerged in the 1930s and World War II—it just popped up all over the place. I came up with graffiti culture and was fascinated by that, and that’s just one of many examples of these things that just sort of magically move through our culture, and it’s really hard to identify or explain [even though] we have been doing it for thousands of years. As long as humans have had societies, we’ve had these ideas that move through society and set the values.

ARTHUR: Absolutely. Certainly animals have always been part of that too. Anthropomorphic animals have been around since ancient Egypt. If you are thinking about this in a Joseph Campbell sort of way, Pepe does sort of figure into [what] we in society are always looking for: we are looking for myth and we are looking for icons to make meaning. Pepe, for whatever reason, became one of those icons.

And he still continues to have resonance in different cultures in different ways, good and bad. The footage in Hong Kong [came to us at a] moment where we didn’t know how to end the film and then all of a sudden we’re just like, “Wait. What? What’s going on right now?” The baton of Pepe has now been passed clear across to the other side of the world and is being used by a different counter-cultural movement, this time in an anti-authoritarian way. It’s fascinating all the different twists and turns.

Arthur Jones has art directed animation and motion graphics for journalists and documentary filmmakers at news outlets like the New York Times, Vice, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and the International Consortium of Journalists. Feels Good Man is his directorial debut.

Michael Premo is a journalist and artist whose film, radio, theater, and photo-based work has been exhibited and broadcast in the United States and abroad. In addition to his work as Executive Producer at Storyline, he has created original work with numerous companies including Hip-Hop Theater Festival, The Foundry Theater, The Civilians, and the Peabody Award-winning StoryCorps. Michael’s photography has appeared in publications like The Village Voice, The New York Times, and Het Parool, among others. He is the recipient of a Creative Capital Award, A Blade of Grass Artist Files Fellowship, and a NYSCA Individual Artist Award. Michael is on the Board of Trustees of A Blade of Grass.