Garden beds designed by individuals in solitary confinement as part of jackie sumell’s “Solitary Gardens,” installed in the Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans. Photo courtesy of jackie sumell.

Editor’s Note

___

How socially engaged art is perceived differs depending on one’s subjective position and experience with the physical locations of the project itself.

We begin with my commentary as Director of Field Research for A Blade of Grass, regularly checking in with the artist and making independent observations of the work. This is followed by a mosaic of reflections by people directly involved in making the project, from those in solitary confinement who designed the gardens to those on the outside who helped build and plant the garden plots in New Orleans. The article concludes with curator Claire Tancons’ longer musing, shaped by both her professional education and her personal history as a descendant of enslaved people who worked plantations in the Caribbean.

We see, too, that the “wheres” revealed by a socially engaged art project are not just its physical location but also what it reveals elsewhere, in this case the conditions of solitary confinement.

The Garden and the Seed

By Jan Cohen Cruz

Driving through the Lower Ninth Ward, which has suffered forced desertion and institutional neglect since Hurricane Katrina flattened it in 2005, I pass a house here, overgrown brush there, but not one grocery store, laundromat, or cafe. So it is a special joy to reach a patch of narrow gardens, each designed by a different “solitary gardener” — a person doing time in solitary confinement — built and maintained by sumell and her team.

Those incarcerated in the United States, especially in solitary confinement, similarly suffer institutional neglect. They are frequently locked up in places invisible to the general public and difficult to get to, with failing economies, places that have a hard time saying no to job opportunities. sumell herself became aware of solitary confinement only by accident. In 2001, while an art student, she attended a talk because she had a crush on the organizer. The speaker, Robert King Wilkerson, had just completed 29 years in solitary in a 6-by-9-foot cell in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, AKA Angola, on a wrongful conviction. The experience shook her to the core: “I met a man who introduced me to a malevolent human construct that I had never known existed.” She asked Wilkerson how she could help. He said, “Write my comrades,” the other two “Angola Three,” also wrongfully convicted and at the time still behind bars: Albert Woodfox, who would spend 44 years in solitary, and Herman Wallace, who would spend 41. Compare this, notes sumell, to the 12-day international bar for solitary confinement, after which irreparable damage occurs to spirit and body.

A painting of Herman Wallace by Langston Allston on the original site of “Solitary Gardens” in the Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans. Photo by Olivia Hunter.

Wallace was a member of the Black Panther Party, and like them, believed he was placed on the planet to “serve the people.” jackie developed a 12-year relationship with Wallace that led to her creation of Herman’s House, an exhibition and documentary feature emerging from his response to her question, “What sort of house does a man who has lived in a 6-by-9-foot cell for over 30 years dream of?” Wallace’s designs featured a garden. He had tried to grow plants in his cell but they withered and died. He realized that he was subject to the same conditions: trying to cultivate life and hope for the future even while facing life in solitary. The house expressed both his hope to one day be free and his desire to contribute to a center for other people.

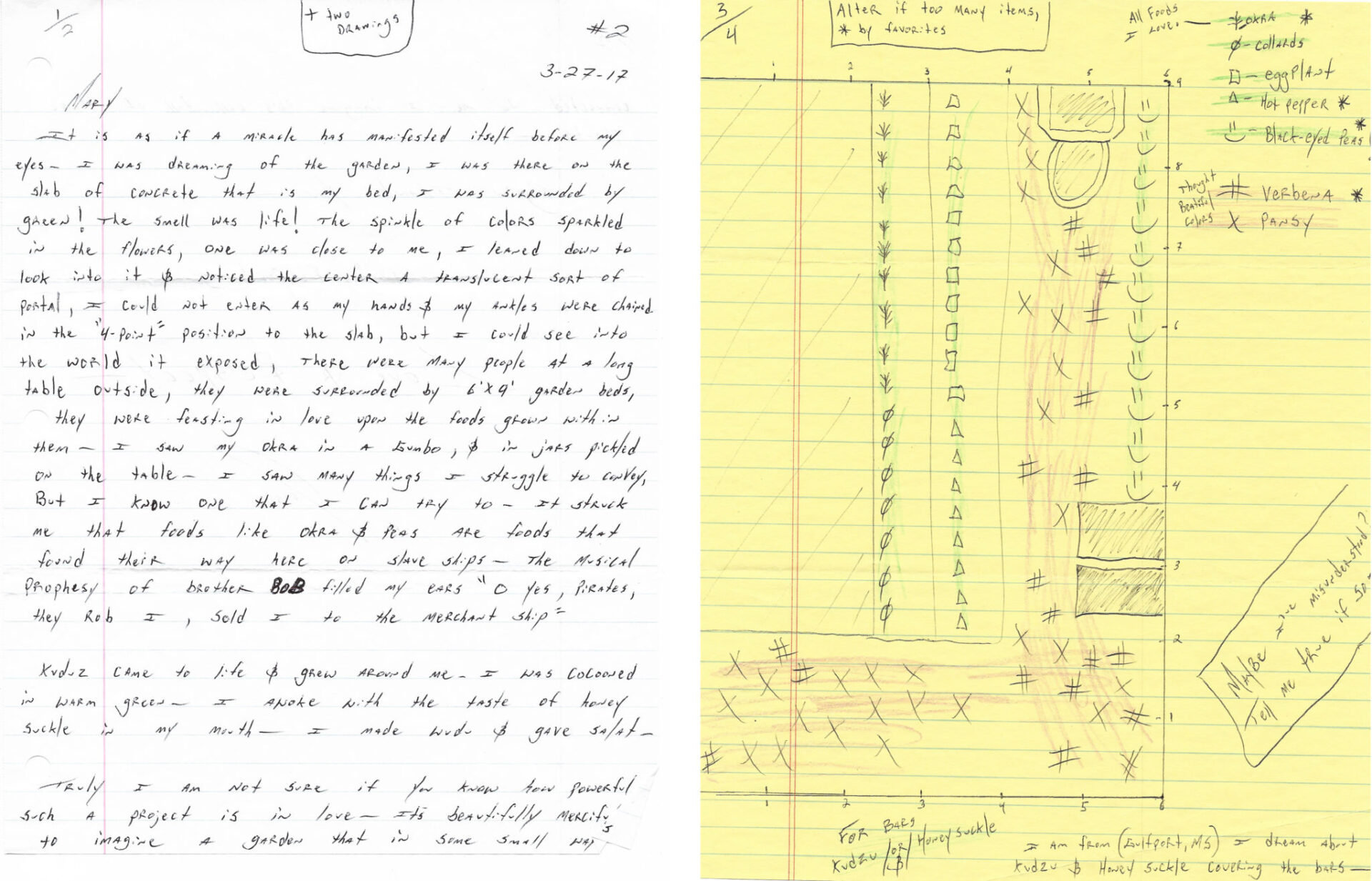

Herman got out of prison October 1, 2013 and died October 4 of liver cancer. Grieving his death, sumell reached out to various prison support networks such as Solitary Watch to contact people in solitary confinement and invite them to design gardens the size of their cells. sumell sent those interested a template marking the fixed items in the cell — the bed, toilet, sink, desk, and chair — with the remaining space available for planting. She provided a menu of flowers and plants including veggies, vines, and hedges that grow well in New Orleans, though they could also request plants not on her list.

By February 2018, seven men in solitary had each designed a garden that jackie and volunteers built and planted. They take pictures and write the gardeners about how their gardens are doing, like what survived a late frost (Jesse’s pansies) and what did not (Zulu’s catnip). sumell and her team are planting three more garden beds in the New Orleans location and going cross-country educating people about the situation, producing more gardens designed by people in solitary.

The “where” of the Solitary Gardens is both the nearly invisible social iniquity of solitary confinement and how that is made visible by its near opposite twin, the gardens. Why does sumell respond to solitary confinement by growing gardens? Why not inhabit a political or purely aesthetic context?

sumell’s art plays a role in the prison abolition movement through its symbolic relationship to impermanence, undermining the prison industrial complex’s intention to make punishment permanent, like “life without parole.” Unlike prison cells whose concrete floors and iron bars communicate inflexibility, gardens wear away. sumell replaced the original wooden garden bed frames with a mix she calls “(r)evolutionary mortar,” made from sugarcane, tobacco, cotton, and indigo — crops that enslaved people arduously farmed. The message, through the decomposing garden bed frames and the fraying ropes that stand in for bars, is, “this can change.” Change is organic and natural. This will not always be.

The garden is both art, offering individual design choices including form, color, and composition, and culture, “agri-culture,” linked to the ecosystem from which it emerges. It reconnects us to the earth, where we come from and where we’ll return, and to the joy, beauty, and usefulness of what comes from it. It is bigger than our individual lives and may outlive us. Along with sumell’s education programs and informal conversations, it offers a broad perspective from which to reflect on the conditions that give rise to the acts that land people in solitary, and perhaps makes a space for compassion.

By chance, on a plane, sumell met a man who builds jails. She knew she would not convince him to change his views on prison in that short ride. But their conversation led her to produce seed packets as a small part of a one-to-one interaction, the beginning of a dialogue about prison abolition. Each packet pictures a plant, including kale, nettles, and dandelions, whose seeds are contained within, and text with contemplative questions and information about that plant’s history. Each is so beautifully designed that someone is not likely to toss it away; the conversation, too, might extend beyond that one moment. The seed packets are yet another “where” of this project, continuing more intimately the work the gardens do in public.

“Solitary Gardens” collaborator Rodricus Crawford. Photo by Olivia Hunter.

Collaborators’ Perspectives

By Jan Cohen-Cruz

People in various circumstances have been touched by the Solitary Gardens — in prison, as workday participants, on school trips, by living nearby. Their insights about the gardens’ meaning suggests why artists do socially engaged art.

Foremost among sumell’s collaborators are the solitary gardeners. Kenny Zulu Whitmore got involved in the garden “through camaraderie with jackie and to help preserve the legacy of a warrior and former Black Panther, my mentor and comrade Herman Wallace.” For Michael Le’Blanc, “Working with the public on the Gardens adds a feeling of self-worth [in contrast to] the typical worthlessness misnomer ascribed to us by the judicial and penal systems [ … ] and allows us to speak from our personality, perspective, and position as people rather than irrelevant prisoners.” For Jesse Wilson, “It not only aids my heart to imagine the garden growing and the entirety of ecology associated with it, it aids the humanity of those who get involved, especially the children. There is such an awakening in the soil, to smell and experience the natural truth that fills the heart that grows seeds.”

People who provide the Gardens with professional services often become advocates. Bob Snead, Executive Director of Press Street/Antenna Gallery, who provides printing services to the project, emphasized that “a lot of folks with different opinions connect to the garden; it’s approachable as a format. Even if they think prisons are acceptable, the garden allows them to contemplate what it means to be in solitary confinement.” Woodworkers Kris and Leslie built the original wooden garden structures and later learned with sumell to build the organic mixture that breaks down faster, serving sumell’s purpose to mirror the hope that solitary confinement, too, will wear away. Engaging with jackie and the Gardens has caused the couple to think about people in solitary differently, especially by seeing their actual living space marked out, so limiting of any movement and so inhumane. They appreciate that jackie both raises awareness of people on the outside and connects with people in solitary.

Mr. Woodfox, of the Angola Three, is now a prison reform activist on the outside. He described jackie’s creative work, both Herman’s House and the Solitary Gardens, as “giving society a look into the mind of a man trapped in a prison cell.” The Gardens are ongoing and fixed in that place, so sustain an opportunity to know people like Herman, even when they have passed.

Mary Okoth, who helps sumell keep everything organized, was moved by the Gardens’ intersection of art, nature, and criminal justice to go to social work school. Imani, jackie’s assistant in 2015, emphasized “the strength of these three men fighting injustice and state oppression, developing rapports with people outside.” She’s as struck by the Gardens’ visual impact as by its investment in a black neighborhood that has been neglected especially since Hurricane Katrina.

jackie hosts occasional volunteer workdays, getting the word out in the immediate surroundings and via social media, both to tend and expand the gardens and educate people about solitary confinement. Local kids playing there learn what it means and enjoy the food it produces. Jacqui Gibson Clark, a co-counselor with a racial equity focus, attended a work day and was moved to tears, especially by the physical experience of making the mortar with materials that enslaved people historically labored over: “When you look at the size of the garden bed, sort cotton, or cut sugarcane to use in the mortar for the garden beds, you can imagine yourself there. Angola was a plantation before it was a prison; this is plantation work. It all comes together. You can’t look anywhere and avoid the legacy of slavery.” jackie invites volunteers to write to the gardeners, so the incarcerated designers learn that people have seen and appreciated their gardens.

Clark sees Solitary Gardens as a “strong, compassionate, and action-oriented” way to engage around racism. “Rather than being about agreeing or not, the activities at the gardens are corporal, as are slavery and racism. The Gardens contrast with the language of opposition, which is often violent and escalates from saying something offensive to a fist, a knife, a gun, a bomb. The garden is a thing we’re building that’s going to go away, practicing impermanence while talking about peace and what we all deserve. It’s a new way.”

Sugarcane crops grown by sumell and her team in New Orleans will be used to make the (r)evolutionary mortar for future garden beds. Photo courtesy of the “Solitary Gardens” team.

Solitary Musings

By Claire Tancons

Editor’s Note

___

How socially engaged art is perceived differs depending on one’s subjective position and experience with the physical locations of the project itself.

An art historian/cultural critic placed in the position of field researcher, I am compelled to look back at the position of the artist/activist as ethnographer — the latter position identified and cautioned against by art critic Hal Foster over two decades ago (The Return of the Real, 1996). In being thrust into conditions of participant observation, I am acutely aware of the impending dangers of both over-identification, as a woman of African descent and enslaved ancestry, and of self-othering, as a non-incarcerated observer with the privilege of a higher education. I wonder how jackie feels about this, in relationship with her own background, and how she averts accusations of self-righteousness common to social justice art projects.

Parallel to the publication of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010), the release of Ava duVernay’s 13th (2016), Jenji Kohan’s ongoing television series Orange is the New Black (2013–present), and the art patron Agnes Gund and funding body The Ford Foundation’s creation of the Art for Justice Fund, artists have contributed to the fight for criminal justice reform with heightened intensity over the last couple of years. Their works call attention to the inhuman conditions of mass incarceration by laying bare its infrastructure of confinement, culture of debasement, and economy of exploitation. Artists have delimited the perimeter of 6-by-9-foot prison cells and donned orange jumpsuits in public (Sherrill Roland, The Jumpsuit Project, 2012–ongoing), locked themselves in cages (Lech Szporer, The Cage Project, 2015), recorded the “acoustics of confinement” (Andrea Fraser, Down the River, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2016), and tallied the numbers of the prison industrial complex (Cameron Rowland, 91020000, Artists Space, 2016).

jackie herself began by building a wooden replica of Closed Cell Restriction “accommodation” (CCR), which she first presented within an art context as part of the inaugural edition of Prospect New Orleans, the international contemporary art biennial, in 2007–2008. How did jackie develop work away from a mimetic representation of the conditions of incarceration to what I would call an organic model of cultural rehabilitation and human liberation with the Solitary Gardens?

The vestigial references to the original solitary confinement cell footprint — the 6-by-9-foot size and front façade of prison cell bars of the garden beds — are overcome by the organicity of matter, the very raw materials of the project such as the sugarcane and cotton plants, and the experimental compounds into which they are turned, like the (r)evolutionary mortar. Further, through their generative qualities, these organic materials are actualized into instruments of transformation appealing for a revision of the fixity of punishment and the necessity for redemption. Having experienced it firsthand during a sugarcane harvest, and currently observing the resistance of the slab of it jackie gave me that I have since placed out in the open on my balcony, I can attest to both the malleability and the strength of the (r)evolutionary mortar. If jackie’s choice of the garden could be understood as a natural extension of Herman’s House, her focus on plant life through permaculture and gardening while furthering her conceptual approach to the structural dismantlement of mass incarceration helps us make the connection with slavery and the mundanity of its reenactment in the prison industrial complex (PIC). Using slave crops as building material for the garden beds really did push the envelope however, or, to use a more apt metaphor, expand her terrain of action beyond a simple critique of the PIC.

There’s an anecdote I’d like to share that is informative about how I situate myself in the conversation about incarceration. In 2009, I went to Robben Island, South Africa, where a former inmate took me on a tour of the infamous carceral complex in which Nelson Mandela and other anti-apartheid political prisoners were kept. Entering the cells gave me the chills, learning that disinformation campaigns ran through forged letters to break the prisoners’ morale left me angry, but nothing made me reel as much as being told that the quantity and quality of food given to prisoners depended on their classification as “white,” “colored,” or “bantu,” a segregationist practice thus reinstating the very racial hierarchies of apartheid the imprisoned had been locked up for fighting against in the first place, within their very organic constitution, the foundation of their incarnated beings. A pretty literal application of Food Apartheid! What I find so profound about the Solitary Gardens is the way in which the partition of the plot between sugarcane and cotton on the outskirts to define its boundaries, and the Solitary Gardens beds right across, allows jackie to expose at once two historical sides of slave life: forced labor around crop cultivation on the one hand, and gardening one’s own plot in the tradition of slave gardens (gardens that slaves were allowed to cultivate for their own sustenance, typically on Sunday).

To speak of the latter historical practice of the slave garden, I’m really peeved at how the solitary gardeners cannot enjoy the fruit of their labor and the taste of the freedom they vicariously acquire through our labor, as the produce we grow for them is not allowed on prison grounds. How to reconcile this practice of liberation through the cultivation of the Solitary Gardens with the prohibition imposed by the prison complex? This operation of liberation deferred and freedom denied makes clear how the common saying according to which slavery is part of the American DNA is not just metaphorical but truly real. For moral deprivation and physical degradation have organically affected our constitution as human beings.

This further puts in sharp relief how important the analogy between the natural plant cycle and wo/man’s “life seasons” is. Having entered the jailhouse as greenwood, King, Woodfox, and Wallace came out as grown trees, and, in the case of Wallace, came out as dead wood, living for just a few days after being released and then returned to earth.

To go back to sugarcane and cotton cultivation and field research … another anecdote, recent this one, stemming from a brief dialogue I had with one of the volunteers who had come to participate in the harvest and had readily grabbed a cutlass to chop down cane shoots. At some point he said how he had enjoyed “the privilege of cutting cane,” and I heard myself respond to him, “well, what you think of as a privilege today was my great-grandfather’s daily toll as a slave.” I was a bit taken aback by what I was quick to think of as naivete, but just a split second later just as surprised by the rawness of my reaction. I was born and grew up in Guadeloupe, in the French West Indies, surrounded by sugarcane fields which are omnipresent on the island and over which my enslaved forebears more than certainly toiled. To go back to where I began with the necessity to acknowledge one’s positionality and intentionality within socially engaged projects: because Solitary Gardens is such a fundamentally embodied practice — from planting, to harvesting, to consuming produce — it is conducive to more unselfconscious interactions that can put in high relief so many of the privileges we don’t necessarily acknowledge as such. These include the volunteer’s privilege to participate in field labor as a young white man and my privilege to contribute field research as an educated black woman raised by middle class parents (both of those characterizations being gross oversimplifications). This is nothing new to anyone with a longstanding experience of activism as an engaged artist like jackie. But how differently do such interactions play out at the Solitary Gardens, and what kinds of new dialogues do they generate? How can our more unselfconscious social selves and more conscientious political subjectivities at once produce and release seeds for change? And how do jackie’s Solitary Gardens come closer to achieving that than most social justice oriented works? Neither the artist, the art historian, the ethnographer, nor the field researcher can. Only the solitary gardeners on the inside and in the outside can, sifting soil through their fingers as others do, and so that others yet may never again have to stick their hands through metal bars to reach our humanity.

Claire Tancons, a scholar invested in the discourse and practice of the postcolonial politics of production and exhibition, is currently a curator (with Zoe Butt and Omar Kholeif) for Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber, slated to open in 2019.

Wilson’s original garden design and written correspondence with the “Solitary Gardens” team. His garden continues to grow in New Orleans under the care of sumell and her collaborators. Photos courtesy of the “Solitary Gardens” team.

Jesse Wilson’s garden in the Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans. Photo courtesy of the “Solitary Gardens” team.