Hank Willis Thomas, All Power to All People, Monument Lab, Philadelphia, 2017 (Steve Weinik/Mural Arts Philadelphia)

Since the summer of 2015, when Bree Newsome Bass scaled a flagpole outside the State Capital of South Carolina to bring down the Confederate flag flying there—just 10 days after an act of racial terrorism left 9 Black congregants of a historic Charleston church dead—the issue of public monuments and the racist legacy actively upheld in our public and civic spaces has become one of the hottest flash points in our current culture war. An issue that spans the racetracks of Nascar to our major cultural and academic institutions, monuments in the United States, paradoxically, represent both our most cherished and our most contested cultural artifacts. What has emerged in the wake of recent, national galvanization around anti-racist protest, is how monuments feel especially emblematic of the duality of American consciousness and identity: a well-pat official version that we learn in school, and then the much darker reality underneath. With the door to that reality blown open to an unprecedented degree, artists have moved in to fill the void in how we should use public spaces for remembrance, and what we should be remembering.

Daniel Tucker is an artist, writer, educator and organizer, as well as guest editor of the forthcoming A Blade of Grass Magazine issue five. As the founding Graduate Program Director in Socially-Engaged Art at Moore College of Art & Design, Tucker has long been tracking how artists and art collectives are addressing the issue of monuments in cities across the country; ultimately engaging larger questions of what role public markers serve in healing historic trauma and creating equitable public space today. In the interest of actively reimagining who is commemorated, and how local and national identity is shaped by these markers in public space, Tucker shares below some of the examples he sees as viable forms for public monuments—or another kind of remembrance—going forward. —Kathryn McKinney

1. Monument Lab

One day, seemingly out of the blue, a 12 foot tall afro-pic topped with an iconic Black Power fist appeared stuck teeth-first into the cement only feet away from the contested monument to former Philadelphia Mayor and Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo, known to advocate abuse and surveillance in communities of color and of social justice activists in his time. Appearing to taunt the bronze Rizzo, which has since been removed due to sustained protest, the statue “All Power to All People” by Philadelphia-born Hank Willis Thomas—while not initially designed for that site—could not have found a more appropriate home. In fact, it was the question of appropriateness that motivated its placement. Part of a city-wide festival of new and temporary monuments in 2017, Monument Lab, 20 artist projects took over Philadelphia premised on the question: “what is an appropriate monument for the city of Philadelphia today?”

The artist-designed “prototype monuments” created for Monument Lab varied in overall approach through media, scale, subject matter and their relationship to site. Thomas’ pic was in a busy downtown plaza just a block away from City Hall where Mel Chin erected a series of wheelchair accessible ramps leading to two identical pedestals each reading “Me” where a dedication might typically name a widely-known historical figure. In that same site, Michelle Angela Ortiz created a video-projected mural “Seguimos Caminando (We Keep Walking)” which grew out of her ongoing work with immigrant families detained at the nearby Berks County detention facility. Blocks away in Washington Square Park two artists took radically different approaches to material. Artist Kaitlin Pomerantz replaced park benches with iconic Philly “stoops” or stairs recovered from front of houses being demolished across the city. In the same site, Marisa Williamson developed a neighborhood walking tour using augmented reality technology that could be downloaded to a smart-phone and allow the viewer to follow a fictional character through a “video scavenger hunt” about the search for Black freedom in Philadelphia’s past, present and future. monumentlab.com

‘I really don’t trust monuments.’ —Michael Piazza, organizer of the ‘Haymarket 8-Hour Action Series’

2. Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM)

After decades of campaigns led by victims of police abuse, their families, lawyers, and social justice activists: in 2008, former Chicago Police commander Jon Burge was finally indicted. It was charged that Burge had overseen and perpetrated the torture of over one hundred mostly African American men at Chicago police headquarters from 1972 to 1991. In June 2011, a group calling themselves the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM) held their first public meeting to talk about public memory of the events.

CTJM issued an open call for “speculative proposals” to memorialize the Chicago Police torture cases. Workshops on design strategies for representing complicated histories were held at local history museums and art centers. Inspiration was drawn from global sources including European Holocaust memorials, Apartheid monuments in South Africa, and creative activism around the history of Military-sponsored disappearances in Argentina. Resulting exhibitions took place at the Sullivan Galleries of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a community gallery, Art In These Times, in 2012 and 2013. Initially the emphasis on “speculation” was essential as the group did not aspire to build bronze statues but, rather, sought to emphasize process over product. In 2015 a coalition including Amnesty International – USA, Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, Project NIA and We Charge Genocide campaigned to get a reperations package for torture victims which was passed by the Chicago City Council for Burge torture survivors and their family members. Among many features of the reparations package included support for a permanent, public memorial to this history. In 2019, CTJM selected Patricia Nguyen and John Lee’s memorial design from six proposals exhibited in the Still Here: Torture, Resiliency and the Art of Memorializing exhibition at The University of Chicago. chicagotorture.org

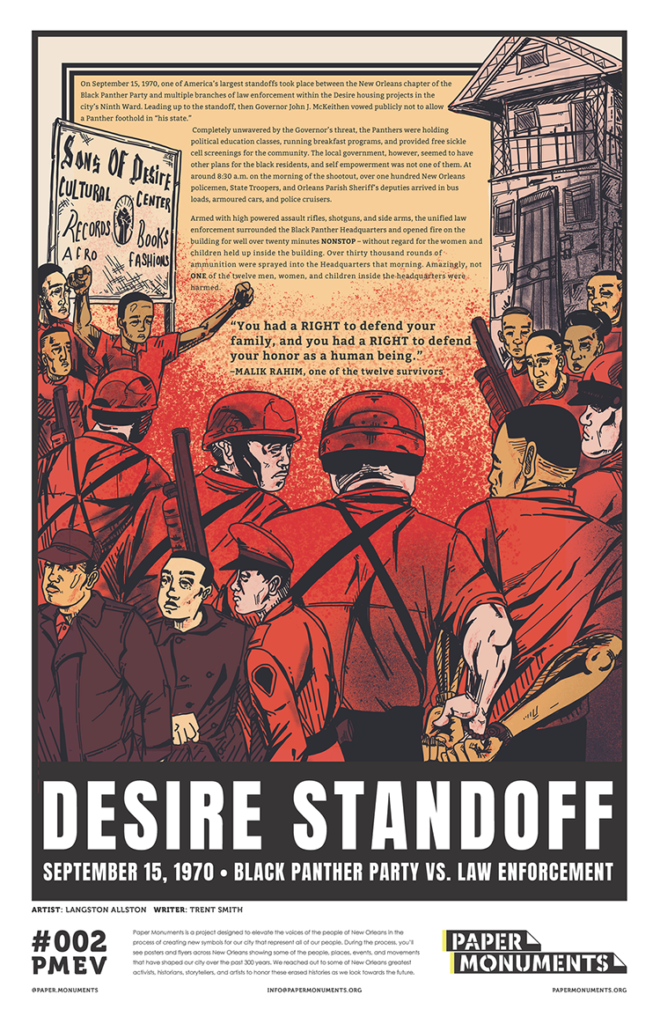

Langston Allston, Desire Standoff, Paper Monuments “Imagine new monuments” poster. Text by Trent Smith.

3. Paper Monuments

In many cities in the Southern United States, the debate over Confederate monuments is drawn as a debate between history as a resource versus history as a burden. This can often be inflected by economic development arguments that insist that the repackaging of the past is actually the only way to draw in tourist dollars.

In New Orleans, the group Paper Monuments has taken this same context of a Southern city that has too long been overdetermined by narratives of racist history and launched a project seeking to offer a corrective. They want to share “the stories that are too often lost or obscured when New Orleans history is recounted. These are the stories of New Orleanians who were poor and working-class. Black and brown. Women and children. Lesbian, gay, trans, and queer. Immigrants and refugees. Those who fought battles for inclusion and justice; those who worked to improve lives and bring hope, but who were and are unlikely to be elevated on any pedestal.” Inspired by the work of Monument Lab in Philadelphia, beginning in early 2019 they launched a series of temporary monuments premised on the question: “What is an appropriate monument for New Orleans today?” papermonuments.org

4. “Haymarket 8 Hour Action Series”

Following the infamous “Haymarket Riot” of 1886, in which both police and workers protesting for an 8-hour workday were killed, the city erected a monument that acknowledged only the loss of police life. The police held “Veterans of the Haymarket Riot” parades until at least the 1960s and the history of the workers was never officially recognized despite inspiring millions world-wide to mark the event with May Day celebrations. The city’s police statue inspired resentment ranging from vandalism to being run over by a disgruntled street-car driver who aimed his trolley at the larger than life policeman.

In 2002, the artist Michael Piazza had the idea for a festival of art projects that would inhabit the circle for 8-hour shifts intended to memorialize the workers’ demands for an 8 hour work day. Piazza’s “Haymarket 8 Hour Action Series” included Soapbox speeches by historians and artists, the installation of a fake street parking sign right on the site that read “No Working: Unlimited Idling 9am-5pm,” a history bike tour, a sewing bee, a puppet show, and a performance using contemporary street-team tactics to connect history to the present called “Hay! Market Research Group.” Further reading available on the history of the space and project in the chapter, “Haymarket: An Embattled History of Static Monuments and Public Interventions,” from A People’s Art History Of The United States.