Quidditch players in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY. Photo by Deborah Fisher.

Editor’s Note

__

In the first of a series of essays about the art institution today, A Blade of Grass Executive Director Deborah Fisher posits an ideal relationship with the institution’s audience as a mutually supportive “virtuous cycle.” The people who make the institution possible, she writes, need to feel like they belong and are valued as participants. She looks at obstacles to that ideal relationship and evokes a fascinating set of examples to suggest a way to get closer to it.

I’ve been thinking about how to make sure all the people who make A Blade of Grass possible feel like they belong, and are valued as participants . . . which feels like a total no-brainer—the most basic, common sense priority an arts institution, or any nonprofit, could possibly set for itself. A healthy art institution is, at root, a productive meeting of art and audience that keeps happening over and over again. By repeatedly bringing art and audience together, ideally the institution hosts and nurtures a virtuous cycle that generates all the things art needs to thrive—meaningful discourse, community, context, and financial resources. I want my work to be easy and successful, and I can’t really think of a more efficient way to feed this virtuous cycle than to make sure the people who make it happen feel good about their participation. But you know . . . every time I start designing it in my head, a funny thing happens. I realize over and over again that this isn’t exactly how art institutions work. Art institutions frustrate the virtuous cycle because they add value through excluding and gatekeeping—deciding what is and isn’t art, what should and should not have an audience, who is and is not a creative person, and so on. A Blade of Grass actively participates in this work, and we have good reasons to do so—discernment and curation are definitely not bad things! But it’s also true that art is unique because everybody is creative and has an imagination, and the art world is applying all this discernment and curatorial control to creativity and the imagination. This means that there’s a potential to at least partially or obliquely exclude and reject 98% of all the people who make the institution possible, and that’s an incredibly inefficient business model. No wonder arts funding is shrinking, everybody’s got gala fatigue, and museum attendance is declining.

This is the first in a series of essays that focus on belonging—why art institutions struggle with it, how we might increase it, and why doing so might make us feel better, do cultural work that is more appropriate and impactful in this moment, and be more financially resilient. I’m writing this series with a perspective that’s broader than A Blade of Grass because most of the opportunities I see are systemic and collaborative—there’s much to address right here at home, but there’s also only so much one little institution like us can do. And it’s going to rely heavily on comparing how we do things in art institutions with the norms and behaviors of lots of other types of formal and informal “cultural institutions”—such as parks, neighborhoods, sports clubs, farmers’ markets, workplaces, bars, and online communities. This is important because this notion of belonging comes up a lot in creative placemaking and socially engaged art discourse, and when it does, it tends to feel like yearning or diagnosing. I’m doing that too! But I want to move beyond yearning for what we don’t have, and into building something that we want, and I think the way to do that is to notice, over and over again, that there are a lot of models out there for imagining how we might approach our work differently. Out in what I guess we could call the “world world,” as opposed to the “art world,” people are actually quite good at engendering precisely that feeling of belonging that I think matters so much to the relevance and sustainability of art institutions! It’s important to see these examples clearly.

Lastly, the reason that this is going to be a series of essays, rather than a list of things that we might lift from other places, is because I don’t think it’s advisable to simply try to do the business of art the way other businesses are done, or copy and paste whole ways of doing things from other sectors. That feels like it’s having a moment right now, and the results can be a little dumb and grim. What I’m advocating is something a little more synthetic and playful. Here’s what I mean. When I am walking in Prospect Park and I notice how the quidditch players1 self-organize right alongside the football and soccer players, I do not conclude that museums should do more sports—that would be a sad, cynical dilution of the core work of the institution. But I do get two great insights that enable a different way of thinking about belonging. First, I notice that there’s an equivalence between the soccer, football, and quidditch teams—the park is not making any judgements about the validity of a fictional sport. Also, the park is a place where you have the agency to both play sports and watch them. The questions that come out of these insights hit the root of my work in a way that brings out a lot of curiosity, possibility, and play—and not a lot of easy answers! There are a lot of quidditch equivalents in contemporary art—forms and ways of making and thinking about art that are not sitting neatly within the particularly mannerist art historical period we’re living in. How might curatorial practice evolve to better see and incorporate artists who are “playing quidditch?” Art can also be a lot more fun and understandable to look at when you’re also engaged in making it. Why aren’t making art and looking at art more fluid and integrated activities in an art institution?

Great art is often hard to see because it can articulate or even momentarily conjure what is legitimately beyond us.

I’m approaching this in a way that preserves complexity and allows for expansive questioning because there is one really good, totally inviolable reason that art institutions don’t engender belonging that needs to be protected. We can never forget that great art is often great because it holds difficulty and paradox. It’s often alien and alienating. It is the one thing that can be both by and about the outsider. Great art is often hard to see because it can articulate or even momentarily conjure what is legitimately beyond us. This is so important—it’s the mechanism by which art propels us into the future! If we don’t keep the fundamental difficulty of art in mind, or otherwise approach this problem of belonging in a simplistic or reckless way, we could craft a well-intentioned plan to turn art into mere entertainment. That’s no good! The art itself can never have an obligation to make anybody feel like they belong. But the art is not the institution—there’s a lot of interesting work an institution could do to hold and bridge that difficulty if institutions weren’t acting as obscure as the art, and if there weren’t so many other, less noble reasons that art institutions aren’t good at generating a sensation of belonging.

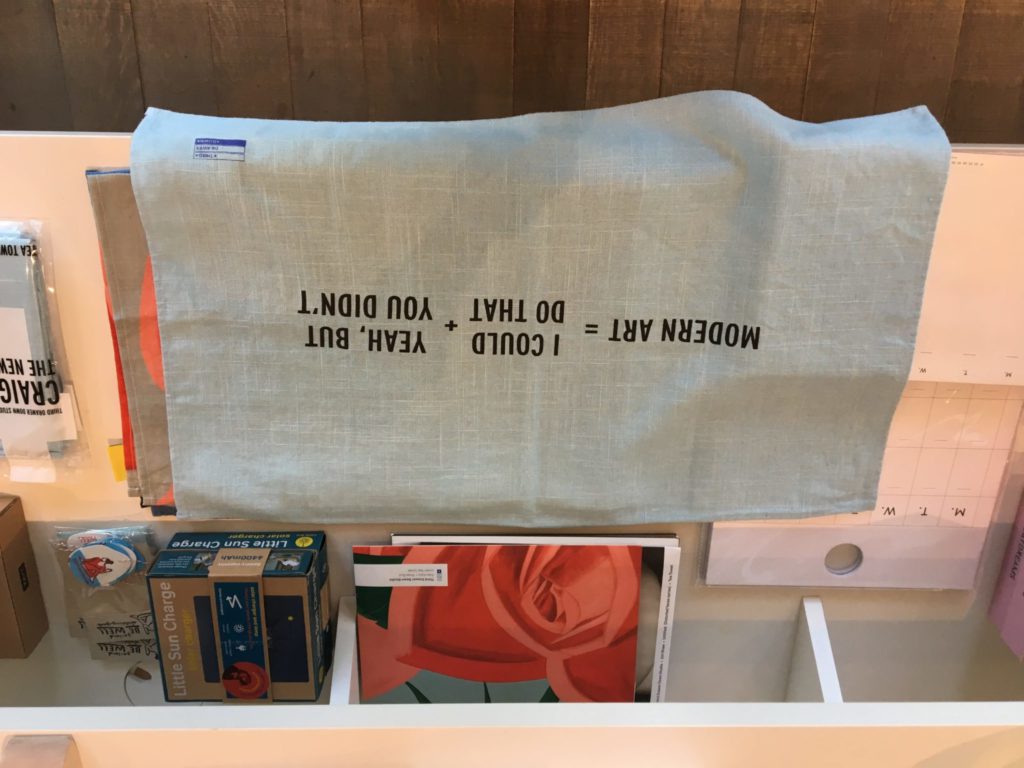

Souvenir handkerchief available in the gift shop of the Pérez Art Museum in Miami. Photo by Deborah Fisher.

By drawing from other examples, my goal in this writing will be to keep returning back to this point, and more clearly articulate what an art institution could do to support, share, and build community for these wonderfully difficult qualities that we cherish and need in art. A really good martial arts dojo, for example, creates a common culture of bravery and inquisitiveness among its practitioners that an art institution might want to emulate. This dojo culture generates helpful peer pressure; sometimes enacts the ideology behind the martial art; sustains a common awareness around things like mindset, body position, or nuances of technique; and holds surprisingly intimate relationships. This dojo culture helps everybody who trains there decide, day after day, to keep coming back to face the inevitable fear, boredom, challenges to the ego, and injury that are inherent in committed combat training. I think art institutions could learn something from this, and invest in creating brave and inquisitive audiences instead of merely explaining art to audiences, to take one example.

Before building such a brave and inquisitive audience, we would need to address the obstacles in our path. Most of the reasons art doesn’t engender belonging are about resources, scarcity, and how art and creativity are being valued. These broadly economic aspects of the problem are easy to critique and difficult to change, but I don’t think it’s impossible. I also feel a responsibility to try. After all, assigning value and managing resources are legitimately the work of institutions. An art institution can’t unilaterally change what resources are available or how art and creativity are valued, but institutions can meaningfully inform this conversation about value, resources, and scarcity by doing their work differently. Institutions have played a role in conflating art with an art market that most of us can’t afford to belong to, and that makes a lot of people feel economically excluded by art. We don’t have to keep doing this—there are other ways to create and maintain an art economy that institutions could model and participate in. Art institutions manage resources, and there are a lot fewer resources than artists in need of them, so a lot of artists feel quite literally and constantly rejected by arts institutions. A Blade of Grass has an open call, so I think about this one constantly!

More broadly, art institutions tend to add value by making decisions about who is and is not an artist, and who does and does not have an audience. I think that this value proposition needs rethinking—art institutions need to figure out how they are adding value by including, rather than either excluding or educating, people. This is important for two reasons. First, decisions about aesthetic excellence have been used to affirm and normalize systems of structural oppression for such a long time that there is no good reason for a lot of people who are making great art, and should have an audience, to trust them. More obliquely, I also think that using exclusion to the degree art institutions do telegraphs an unintended message to audiences, and that a lot of people who could love art because they’re deeply creative people simply don’t like being told, even indirectly, that they somehow lack creativity and imagination because they aren’t called artists.

Demonstration by Hayato Osawa Sensei at United States Aikido Federation Summer Camp. Photo by Javier Dominguez.

Increasing belonging in an art context is about recognizing how belonging is generated elsewhere—noticing that quidditch players belong in Prospect Park—and using these examples to play with these intractable-seeming barriers to belonging that stem from how art is valued and resourced, such as the way we currently value a quite narrow range of artistic expression. This play, I hope, will be fun, like play should be! I am writing from a place of genuine joy. In his book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari writes that this innate human ability to create culture, or ways to belong together, is an evolutionary accelerator—it takes us out of the impulses and limitations presented in our DNA and helps us collectively imagine ways of being that are far more complex, flexible, responsive, and generative. I believe this, and notice that I am in a state of joy when I participate in this process. In the essays that follow, I’ll be writing a lot about my own life and how I get a lot out of a bunch of communities that I belong to. A big motivator in this writing, and in my own institutional practice, is the sense of wonder I get out of these collaborative experiences that grow and transform me. They transform me because I feel connected to others through them, and feel safe enough to be vulnerable in them, even when the experience is quite challenging.

I really do believe that art’s difficulty and paradox could also be harnessed more collectively, and put to really good cultural use right now.

But I also want to keep in mind that the reason to engage in this play is actually quite serious and consequential. As the fundraiser-in-chief at A Blade of Grass HQ, I’m concerned that art just doesn’t seem to quite have what it needs to thrive. It’s not just that funding is shrinking and participation is declining—the reasons to participate don’t add up as nicely as I want them to. And that’s really a problem because I believe in art, and what it can do for us on a more societal level. I’m sure you’ve noticed that along with the insect populations vanishing and Antarctica melting and all the wealth rapidly consolidating and OMG what is going on with Brexit and on and on . . . a B-list reality TV show celebrity with absolutely no political experience has been the President of the United States for a couple of years even though he got elected with what’s looking like significant help from Russia, and as of this writing has kept the government shut down for a month because the most important pressing agenda item of his administration seems to be stoking white identity politics and fear about immigration rather than serving the American people as a whole by keeping things up and running. This is a moment in which power is being expressed and maintained through manipulating and shaping a culture—by raging on Twitter, fighting a decades-long culture war between “real Americans” and an “elite ruling class,” and inciting a tremendous amount of tribal fear. And this cultural power is hurting a lot of people, including people who voted for this president. Art’s difficulty and penchant for paradox has historically been used to create this culture war—we helped make this Two Americas by creating institutional practices that kept art separate from people. But I really do believe that art’s difficulty and paradox could also be harnessed more collectively, and put to really good cultural use right now. We are stuck in a truly dismal cultural moment that is probably not going to be resolved without holding difficulty and sitting with paradox. If art institutions approached their work differently, in a way that enabled high-trust, productive conflict and engaged a lot of different kinds of people in making and enjoying art and culture, I think we could figure out how to hold this moment bravely and curiously, in all of its difficulty, divisiveness, and fear. Just doing that—simply creating a place where we could bravely move through the fear instead of endure it or hide from it—would actually do a lot to help to create the next cultural moment.

Ultimately, I am writing to try to create that possibility.

Notes:

1. Quidditch is a fictional sport created by author JK Rowling for her Harry Potter series.

Deborah Fisher is a creative leader working to expand the roles artists, creativity, and culture play in civic life. She is the founding Executive Director of A Blade of Grass. Fisher has served as an art, strategy, and philanthropy advisor to Shelley and Donald Rubin, and has worked in many capacities at the intersection of art and civic life in New York City, including as studio manager at Socrates Sculpture Park, and as a curriculum developer for the Brooklyn Center for the Urban Environment. Her approach to leadership is deeply informed by her artistic training and experience making public art.