The Actors’ Gang Prison Project, one of the community partners of Future IDs at Alcatraz, showcases an improvised theatrical performance at one of the monthly public programming events to coincide with the Future IDs exhibition. Photograph by Peter Merts.

Who is a criminal? Who gets to decide what standards of conduct are deemed binding by the rest of the community, or what the punishment for breaking the standard should be? The where and when and how by which ideas of normal behavior and identity are established and enforced are complicated by myriad subtle, unnoticed, and unspoken human contexts. These are not just abstract questions: they have dramatic and sometimes heartbreaking real-life consequences.

The Future IDs at Alcatraz project makes publicly accessible the poignancy of such questions in particularly forceful ways. It does so by representing the aspirations and disappointments of scores of very real humans affected by the stigmatizing and restrictive norms of incarceration. Future IDs at Alcatraz was initiated by artist Gregory Sale, whose creative social practice has primarily engaged people with direct experiences of prison, jail, probation, and parole in interactive exchanges about the impacts of incarceration. The exhibition and a series of programs runs from February through October 2019 on the site of the notorious island-based Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary itself.

Visiting prison for even a short period makes apparent how bleak the physical and psychological realities are for anyone locked up against their will. As a teacher in a “correctional facility” previously myself, I witnessed the tense and antagonistic social dynamics that can form between prison staff and prisoners. I observed the extreme and hostile factionalizing that can develop among different groups of prisoners as well, and I heard firsthand the traumatic personal stories of so many people forcibly channeled into the complex penal system of courts and detention. Lives are damaged by those interactions, even long after being “released.”

Future IDs at Alcatraz summons feelings of compassion through personal testimonials in word, image, and bodily presence about the past and present circumstances of individuals with conviction histories. As importantly, participants in the project generate multiple distinct outlooks striving toward better futures. Individually designed and artfully produced alternative identification cards are blown up to outsized dimensions to offer spectacular viewing for visitors. The idea of generating newly imagined self-identifications alternative to those issued by prisons grew out of meetings instigated by Sale with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, a support network for current and formerly incarcerated men and women. The first handful of those who helped conceive the goal of creating new identities promulgated the idea among a growing constellation of prison-impacted individuals and more than twenty other organizations.

Future IDs Artworks and Their Creators

Many of the personal goals depicted in Future IDs re-inscribe different kinds of “normal” while also trying to parry or deflect them. The standardizing implications of digital barcodes for identifying products and people, for instance, are played upon by multiple Future IDs artist-participants in their banner-sized ID cards.

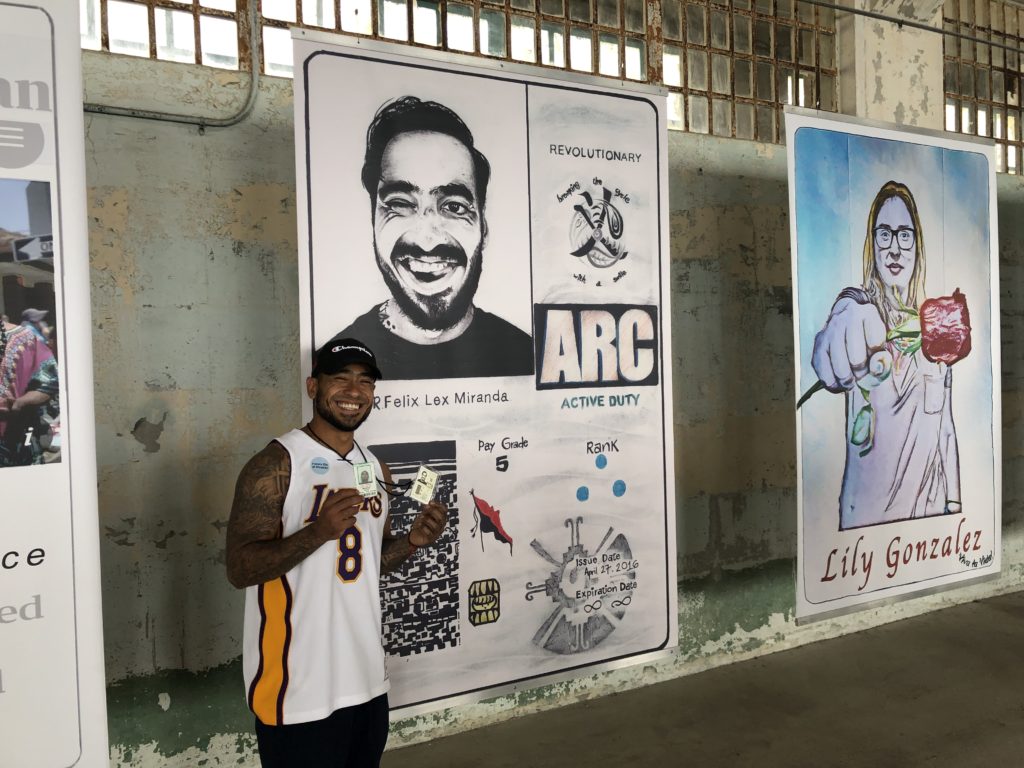

In the complicating manner of a trickster figure, Felix Lex Miranda’s winking self- portrait highlights an idiosyncratically-rendered version of a barcode made up not simply of generic strips of black and white but hieroglyphic icons that imply a more complex world of cultural understanding than the simple numerical data-coding marks. In a further jousting with the conventions of ID cards, Miranda inscribes an infinity sign as expiration date for his self-stated position as “Revolutionary,” and also incorporates “ARC,” the acronym for the Anti-Recidivism Coalition.

Felix Miranda poses in front of the personalized ID he created as a participant in the Future IDs at Alcatraz project while holding up his

former prison-issued ID. Photo by Jear Keokham.

The core team that coalesced around Sale included Dr. Luis Garcia, Kirn Kim, Sabrina Reid, Jessica Tully, and many others who shared the goal of “shift[ing] thinking about rehabilitation, reentry, and reintegration.” In addition to exhibition co-curators Sara Cochran and Chris Sicat, the project also relied on collaborative design and labor both in prisons and other communities by Ryan Lo, LaVell Baylor, Dominique Bell, Aaron Mercado, Jamee Crusan, Sara Daleiden, and Emiliano Lopez.

Among the other self-portraits to emerge was the particularly abstract figurative image by John Winkelman, who is still incarcerated. The cyborgian face that Winkelman generated in the form of a QR code leads online to the Project Paint website, profiling additional artwork produced in prison—an expansive use of the communicative possibilities of otherwise standardizing or utilitarian digital codings.

Another strategy of Future IDs’ portrait-makers is finessing the conventions of the usually limiting identity card to include an array of multiple identifiers. For example, Réne Hernández’s detailed illustrations in word and image: “Journeyman Electrician/Community & Family Member/Father of Two.” Juan Sanchez also lists multiple tags of identity: “Art Mentor,” “Substance Counselor,” and “Productive Member of Society.”

In perhaps the most prolific instance, Michael De Griego cites the several Indigenous nations (Hopi, Tewa Pueblo, Manitoy, and Jicarilla Apache) with which he traces affiliation. He employs multiple images of other humans (including an Indigenous person crying out in full regalia, along with one of himself) as well as an array of animal spirit images such as a fish, bear, armadillo, and wolf, drawn with various degrees of realism and stylization. He uses a handful of different designations naming himself “Christian. Humanitarian. Activist,” and, in all caps, “HUMAN BEING.”

Among the singular, not-politics-as-usual identifiers chosen for self-portrayal, Candice Price redrew a page from the newspaper The Guardian that features her militant defense of an elected official. The reproduced headline reads, “Rightwing rally cancelled as Maxine Waters supporters stand guard,” a complex layering of identification with an official representative on the frontlines of social conflict.

Future IDs at Alcatraz in Context

The regime of prison acts as one intensely defining context for reckoning what and how norms come to be—not only for those incarcerated, but throughout societies where values and resources are measured out in relation to perceived transgressions. Social divisions stem from judgments of what is good or bad, right or wrong, and they cordon off possible roles from those who transgress them. This determines not only who has greater degrees of liberty (and who turns the keys in locks by judging, confining, and penalizing others’ lives), but who has access to education, jobs, and social networks—and who doesn’t.

The sense of social shame projected on individuals who become caught up in the criminal justice system is perpetuated by media accounts containing latent judgments against those labeled as criminal. That shame has real-world effects for those who bear such judgments, as participation in work, school, and interpersonal relationships can all be radically curtailed or distorted, or simply impossible to imagine.

A roundtable discussion led by Future IDs collaborator and artist Kirn Kim as part of the series of public programs coinciding with the exhibition of ID-inspired artworks on Alcatraz Island. Photo by John Contreras.

If prisons are significant sites where society sets its own limits—and isolates and punishes those who trespass those limits—the most celebrated prisons are likely then candidates for considering what effects these intensive enforcers of normalcy might have on society and individuals. Alcatraz, infamous as a location for human confinement and disciplining, was closed in 1963 and reopened in 1972 as a major tourist attraction that serves as a reminder of incarceration.

Alcatraz Island today presents the stripped-down remnants of the penitentiary that detained thousands between 1934 and 1963. It is mostly now just non-functional infrastructure: bare, crumbling walls and rusted metalwork. The US National Park Service has added signage, a gift shop, and an ongoing series of introductory verbal messages from National Park Service Rangers who meet each arriving tour boat. For the last thirty years, the site has also offered versions of an audio tour recounting what life was like on the island when the prison was still in operation, as well as anecdotes about some of its most notable prisoners.

While the majority of official programming on contemporary Alcatraz has focused on historical particulars, a handful of more recent projects—particularly art projects—have surveyed present realities and speculated on future possibilities related to the island’s identity and its place in larger society. The long-developing contemporary art project Future IDs at Alcatraz involved the efforts of a multitude of individuals impacted by the criminal justice system, while using Alcatraz as a platform to provoke questions about how standard definitions of individuals and their behaviors can default to singular, highly skewed, and even damaging identifications.

The Future IDs project produced nearly a hundred self-portraits, of which forty were hung for public viewing at Alcatraz. While the ten-month-long exhibit features a number of different events, the primary artifacts that remain throughout are the larger-than-life ID cards, which subvert the enforced norms of the cultural conventions from which they’re derived.

The diverse styles and aspects of the Future IDs banners add lively color and texture to the otherwise desolate shell of Alcatraz’ cavernous New Industries Building. More significantly, the IDs’ content acts as a catalyst for visitors to think about the lives of individuals impacted by incarceration while overwriting the stigma projected onto them by would-be normalizing judgments of the US justice system. Among Sale’s intended outcomes for the project is validation for participants who are trying to move beyond the constrictive stigma of having been imprisoned, and to demonstrate how their efforts to be seen on their own terms can be successful both in terms of their own reentry experience as well as how others see them. The ripples of public notice for the project also impact those still inside prison (40% of the participants in the show), making connections for them to those already succeeding outside. With a 60–70% recidivism rate, that kind of possible affiliation is no small difference.

Prisons have been so commonplace for so long that most never question their existence or growth. This normativized status demonstrates the power of ideologies—even amidst highly conflicting impulses and beliefs. Whatever one’s opinion of prisons (a word whose linguistic roots signify “taking hold” of something or somebody), the claims and after-effects on individual lives are extraordinary. Future IDs at Alcatraz works against the normalization of associated and narrowly constrictive social judgments. As one participant in the Future IDs program put it during a public event on Alcatraz: “In the case of the incarcerated, most are defined by the worst thing they ever did.”

In further illustration of the challenging status quo that Future IDs is attempting to move beyond, one formerly incarcerated participant rhetorically asked: “Who thinks about a guy in San Quentin who wants to be a ship captain? Who thinks about a guy in San Quentin in the first place?” These questions were perhaps a reference to the still-imprisoned Bruce Fowler, whose “Captain’s License” self-portrait was on display in the next room at Alcatraz as part of the Future IDs public exhibition.

Community Programs as Art

The humanizing effects of static visual artwork are limited, however, and even the most stimulating effects of visual art can remain isolated in a rarefied world of abstraction, no matter how persuasively depicted alternative realities might be. Future IDs at Alcatraz has addressed this by encouraging social interaction during its various phases of production, gently choreographing a multitude of encounters through public events held on the third Saturday of each month of the exhibition’s run.

During those events, people impacted by incarceration have shared personal accounts directly with friends, families, and strangers. My encounters with Future IDs’ participants were far from the only experiences among visitors that triggered deep upwellings of emotion and prompted reconsiderations of presumptions about what people who have been subject to the justice system might be like.

The Future IDs artists regularly attend these programs and events. Perhaps no more effective means could be conjured for providing alternatives to the stigma of “convicted felon” than the actual embodiments of difference that complex, nuanced, and feelingful individuals are able to assert through their own physical presence. The self-portraits in the form of identity cards—more like boldly declarative flags when blown up in large scale—serve as backdrop for those embodiments, proof of the work that has been done to think through what might be uncomfortable and/or problematic in identifying definitions by legal code, and to provide alternatives, some of which are attainable while others are pipe dreams due to the myriad of legal restrictions placed on those with a conviction history.

Participants in the Future IDs project also embody some of these positive feedback loops back in the “real world” of other, still-functioning prisons and society at large. Returning as a visitor to Calipatria State Prison, where he’d done time seventeen years before, the formerly incarcerated Kirn Kim was called upon to speak to the many still-imprisoned individuals gathered for a special concert event in the yard. Kim understood from their response the kind of impact his story of release and forming a new identity outside of prison could have in providing hope for those still inside. Kim became both a participant in the Anti-Recidivism Coalition and a key organizer for Future IDs at Alcatraz. His Future ID depicts that pivotal moment when he unexpectedly connected with those still being held in the Calipatria yard.

An Entry Point to Discussing Human Rights and Social Justice Issues

Meanwhile, Alcatraz’ status as a destination for tourism continues to present not only opportunity for historical interpretation but also, among a more progressive cohort from the National Park Service through its non-profit affiliate the Parks Conservancy, consideration of what the past might have to say about society’s present and future values. The Parks Conservancy and the National Park Service have undertaken a slow-building series of initiatives to provide more substantial and wide-ranging critical considerations of the historical roles and purposes of Alcatraz, including its role in the US prison system, as a site of enforcement for cultural norms, as well as other events with conflictual foundations, such as the 1969–1971 Native American Occupation of Alcatraz.

As part of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, through which more than 250 member organizations promote dialogue on contemporary issues of human rights in sixty-five countries, Alcatraz has expanded on the types of cultural preservation and interpretation it provides through its overseeing National Park Service body, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. For example, it has preserved murals and graffiti from the Occupation, and produced an online series of images and essays documenting earlier US imprisonment of 19th century Hopi resisting forced relocation of Indigenous children for English language education. Additionally, it holds documents regarding the confinement of Hutterite pacifists on the island for their refusal to serve in the US military campaigns of World War I.

There have been a handful of expanded and highly relevant newer public cultural offerings at Alcatraz as well, including 2014’s Ai Weiwei @Large, which pointed to specific issues of global concern such as political imprisonment through lenses of contemporary art presentations. These newly activated uses of the former prison to consider issues of continuing social importance signal the more intensive possible engagement that such context-specific cultural projects can catalyze for public visitors at Alcatraz.

The majority of the 1.5 million-plus annual visitors to the island will likely continue to be caught up in the tours of physical cell blocks and biographies of Machine Gun Kelly, the Birdman of Alcatraz, and the like, at least for the foreseeable future. However, those lesser but still substantial numbers of visitors who either make the trek to the island specifically for contemporary art events like Future IDs, or encounter by chance exhibitions and experiences curated explicitly to represent contemporary viewpoints once they are actually on the island, can have their perspectives transformed.

At the same time, the social stigma of incarceration will broadly remain for those who become imprisoned. Calls for prison reform or outright abolition develop mostly in communities inordinately affected by the criminal justice system, as well as along the radical margins of political activism and within academic settings more than in any sustained mainstream political realms. The activism of the Future IDs project gently prompts thinking about how a person can move into a better future once released from prison. As such, it is more determined to shift the thinking of and about those incarcerated than to directly critique the idea of incarceration itself.

The vocational tendencies of would-be reformers to make better citizens are usually understood as positive, but they can also be seen as submitting to another mode of normal. Many of the new identities that the Future IDs artworks display—“Teacher,” “Life Coach,” and “Youth Advocate”—remain entangled in a social system that values only certain human endeavors—and productivity foremost, perhaps. The channeling of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals toward becoming “productive” members of society might be one likely direction to follow in order to imagine a future after the constraints of prison. However, there is danger in pressing vulnerable individuals to conform to certain ideals that might be difficult to attain in a society whose underlying structural basis is understood by many to be fundamentally unequal.

Meanwhile, the majority of people who come to visit the former penitentiary on Alcatraz will encounter only the hard surfaces of bare buildings, revealing little about the impact of prisons on lives continuing to languish and chafe today, nor those confined and constrained in generations before. Any more direct or immediate address to a system of laws and ideologies that prescribes incarceration will seemingly have to occur much more offshore than on the island itself. But on Alcatraz, at least some reminders are being proffered by projects like Future IDs and the developing programs of cultural interpretation by the National Park Service to reflect on the harshness of the prison regime’s effects on those impacted by incarceration—which is, arguably, everyone in society today.

Writer, curator, media artist, and teacher Brian Karl has served as Artistic, Executive, and Program Director at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Harvestworks Media Arts, and Headlands Center for the Arts, and has provided curatorial, programmatic and technical consultation at Art-in-General, Creative Time, and the Kitchen. His writing has been published in art-agenda, Artforum, Flash Art, Frieze, Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Migration Studies, SFMOMA’s Open Space, and Yishu Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art. His media work has screened at the Jewish Museum (NY), the Kadist Foundation, and as a part of the Whitney Biennial and the New York and San Francisco Film Festivals. His screenplay, Cybersyn: The Computer and the Socialist, on the role of cybernetics in Salvador Allende’s socialist-led government in Chile in the 1970s, is an official selection of the 2019 Oaxaca Film Festival.