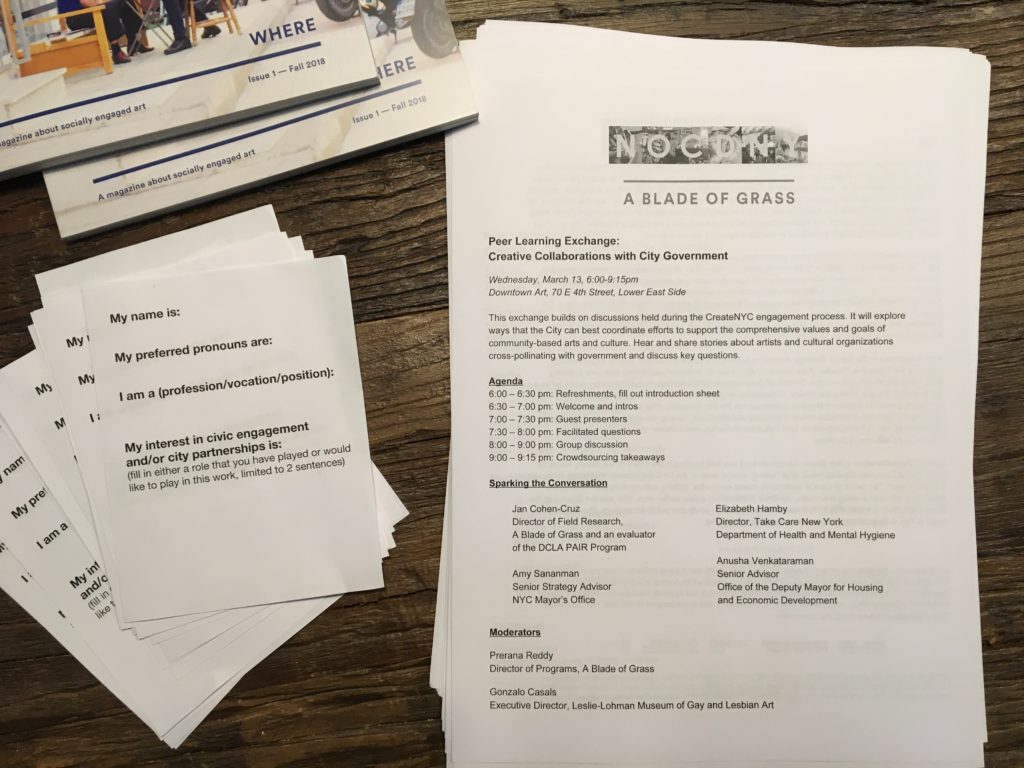

In March 2019, A Blade of Grass and NOCD-NY co-hosted Creative Collaborations with City Government, a peer learning exchange and discussion about the diverse ways arts and cultural groups can intersect with city government, emerging opportunities for collaboration, and best practices for working together. Naturally Occurring Cultural Districts (NOCD-NY) is a citywide alliance of cultural networks, community leaders, and artists focused on the creation, advocacy, and preservation of arts and culture at the neighborhood level. A Blade of Grass shares NOCD-NY’s belief in the power and necessity of community-based art in civic life. The learning exchange was facilitated by A Blade of Grass Director of Programs Prerana Reddy and Executive Director of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art Gonzalo Casals (both also NOCD-NY board members).

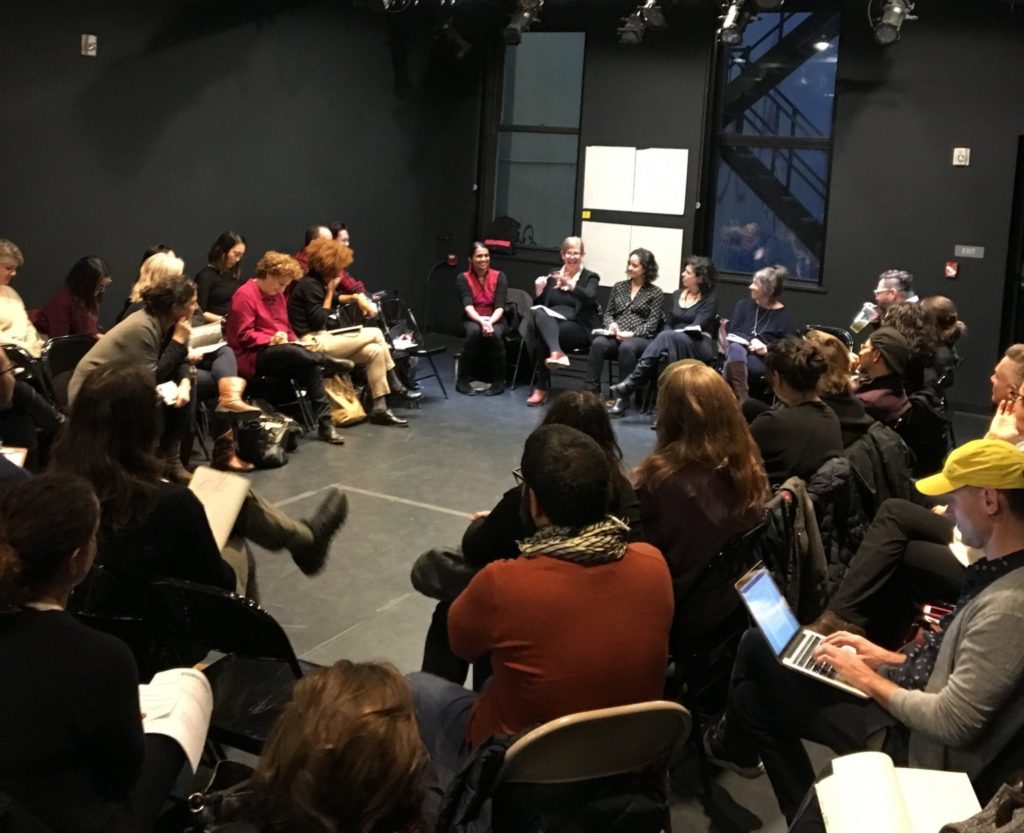

The exchange brought together a panel of four “instigators” currently working in government but with a history of community-based cultural work, who shared their work and experience as a way to kick off the discussion. The group determined that despite challenges arising from the different methodologies arts and culture groups and government take towards serving communities, the landscape for effective collaboration between these entities in New York City is important, with many frameworks already in place or developing; and that it is possible for arts and culture to in fact have a hand in restructuring city government.

The instigators:

– Elizabeth Hamby, Director, Take Care New York, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

– Anusha Venkataraman, Senior Advisor, Office of the Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development

– Amy Sananman, Senior Strategy Advisor, NYC Mayor’s Office

– Jan Cohen-Cruz, Director of Field Research, A Blade of Grass, and evaluator of the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs’ Public Artist in Residency (PAIR) Program

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed are solely those of the individual and do not represent the larger government agency or organization.

Elizabeth Hamby opened by acknowledging a history of state systems embedded in oppression that have a negative impact on social, emotional and physical outcomes (including health) of communities, reinforcing inequities across race and incomes. But she highlighted the importance of understanding government agencies as nuanced, not monolithic, entities. These agencies are comprised of people with diverse histories and experiences, many of whom, including Hamby, bring creative approaches to policy and problem-solving, and a capacity for systems thinking from their past work outside of government. Hamby describes herself and other artists creating change from their positions in government as “NOAIRs,” or naturally occurring artists in residence.

Anusha Venkataraman stressed that her past experience managing El Puente’s Green Light District program, which aims to sustain, grow, green, and celebrate Williamsburg’s Southside community, informs her current work at the Deputy Mayor’s Office of Housing and Economic Development. She highlighted the ways that community-based urban planning and policy work have given her a comprehensive perspective, allowing her to bring a wide swath of government agencies together to creatively solve problems, more effectively liaise with communities and prioritize their needs, and mediate various barriers or constraints, saying, “I think cultural organizers intrinsically understand their communities, and being involved in our work is critically important.” Venkataraman shared her experience helping secure a vacant lot in Brownsville for a cultural center, and encouraged arts and culture workers to take advantage of opportunities to collaborate with government, pointing out that, “Just because it’s difficult doesn’t mean it’s always ‘not possible.’”

With the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, Amy Sananman ran the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP), which created conversations in the agency about the important role of neighborhoods and community institutions in the co-production of public safety: a group effort that must invest in people, build social cohesion, engage in placemaking, and strengthen pathways of communication between neighborhoods and government. Sananman also highlighted the unique opportunity and responsibility of cultural workers to help create imaginative cultural shifts away from systems of oppression like mass incarceration. Focused on closing Riker’s Island, Sananman suggests, “We have to grapple with the cultural norms question to reduce who’s behind bars.”

Jan Cohen-Cruz drew upon her work creating a national field scan of artists embedded in government with Animating Democracy, as well as her findings as evaluator of the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs’ PAIR Program, to highlight the symbiosis that occurs in these partnerships, situating it within Mayor DeBlasio’s notion of “one city rising,” a counterpoint to a “tale of two cities.” Cohen-Cruz cited former PAIR artist Tania Bruguera’s project CycleNews as an example of a boundary-dissolving project. CycleNews tapped a community advocacy group of bicyclists in Corona, Queens to bring information about relevant government services to immigrant communities, and to bring those communities’ self-identified needs back to the city, simplifying communication and building trust between the two groups.

The conversation drummed up some questions and responses among presenters.

How do we grow truly collaborative relationships between arts and cultural organizations and government, moving beyond the juxtaposition of one to the other?

– Advocacy, challenging government, and questioning government is important to transparency; transparency is important to growing relationships. Folks on the outside of government can focus on advocating for their communities’ needs, highlighting to government what’s missing, and holding government accountable. Folks working inside government can think through and create systems for long-term commitment to communities’ needs

– Change in city government is slow and cumulative, but individuals within agencies are already implementing a more progressive, cultural approach. The field should continue to “infiltrate the ranks” as staff to represent these values. Tamara Greenfield, Deputy Executive Director, Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety / Building Health Communities summarized, “As agencies, we’re pushed to think from 30,000 feet up. Systems regulate for a reason, but something art and culture can do is push the view back to why it matters.”

– Arts and culture workers should think expansively: beyond just meeting the government’s terms, we are poised to identify issues and solutions. Amy Sananman encouraged folks to ask, “What is your value proposition and how can you make a strong argument for that? If you have a plan or a path, we [government agencies] will connect you with the right people.”

How can we set arts and culture up to be resonant and sustainable within government?

– Artists in government must navigate not being at the center of their art project—this work is about civic practice, rather than social practice

– Create structures for arts and cultural workers to organize and talk together. One example is the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Project Space’s SHIFT Residency, a peer support group and studio space for arts workers

– Create buy-in from city agencies by making opportunities for government employees to be a part of the process, and build a framework for the project to be handed over to the municipality or a community-based organization and sustained after the residency ends

– Government agencies should engage the arts in public decision-making and fund-allocation around neighborhood development, and include artists in capital projects

In the discussion that followed, the group shed light on the following themes:

Opportunities for collaboration between artists/arts and culture organizations and government

– Opportunities include things like art residencies within government (namely the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs’ Public Artist in Residency (PAIR) Program); city capital projects; and advocacy for arts and culture spaces through existing government programs, such as NYCHA community centers

– Plug into city initiatives—like ThriveNYC, which focuses on mental health—that already operate within a framework that acknowledges the need for a cultural change; relies on the convergence of a vast network of stakeholders; and values communities’ input. Another example is the importance of community culture in informing CPTED (crime prevention through environmental design) efforts, like how the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety works towards infrastructure upgrades, community gardens, extended hours for community centers, and activating public spaces

Ways that arts and culture can play a part in restructuring how city government operates to allow for greater democratic participation

– The 1976 New York City Charter revision created a framework for communities to be more involved in neighborhood city planning by adding section 197a. The charter is being revised in 2019 and the public can participate in open meetings

– Arts and culture can be used as a lens to evaluate neighborhood zonings, using tools like the Cultural Blueprint for Healthy Communities

– NYC’s new Civic Engagement Commission presents an opportunity to make our voices heard about the value of arts and culture

– Arts and culture are engaging community through NYC Council Participatory Budgeting, which also provides a platform for citizens to allocate funding towards a neighborhood’s cultural needs

– Upcoming political transition at the local and state levels presents an opportunity to build strategies and establish processes for structural change. Caron Atlas, Director of NOCD-NY, pointed out that it’s local arts and culture who are doing the work on long-term goals in neighborhoods, saying, “There are cultural organizations, cultural councils, and grassroots structures that will be keeping things moving regardless of who’s in office. Is it too visionary for community to create the vision and for the city to help realize the scale?”

Tips and suggestions for effective collaboration

– To encourage the city’s recognition and support, arts organizations should clearly illustrate the value of their work to agencies. For example, the policy brief Arts and Culture for a Just and Equitable City—created by NOCD-NY, Arts & Democracy, and Groundswell—lays out four major outcomes of arts and culture work: creating cross sector strategies, inspiring participation, cultivating community capacity, and furthering cultural equity

– Although it is tempting to step away from a city process in fear that it lends legitimacy to something that’s inequitable, airing a grievance to the media before taking it up with the city itself is a lost opportunity for the city to learn

– Artists partnering with government agencies should create a sense of belonging and convey that municipal staff matter in the project. When city staff participate in the creative process, they understand what it produces and can help build buy-in and support

– Artists and cultural workers should contribute to community efforts; serve on the community board in their neighborhood; and/or connect with their communities and local government as a neighbor and fellow citizen beyond their identity as an “arts worker”

Challenges

The group identified that a key responsibility of collaborating with government is to define and make a case for the value of art, which requires evidence of its impact. Participants grappled with the challenge of such a responsibility, some advocating for quantitative, data-driven evidence and others for qualitative storytelling on account of its emotional impact. Liz Crane of ArtPlace posed a question: “How do you talk about the impact of arts and culture when it is process-based work?”

Backing up a step, the group identified that evidence-based practices are sometimes rooted in white supremacy or other oppressive systems—what’s “proven” to be fact or truth is not always objectively so, especially across lines of race, class, and socioeconomic position.

Bureaucracy in government is also a challenge and can lead to delays in arts and culture projects. An example of this is the funding allocated for the Gowanus Houses Community Center through both the Participatory Budgeting process and a commitment by Mayor DeBlasio. Participants noted that bureaucracy means the process to reopen the space as a Cornerstone moves very slowly, as the city won’t identify an operator until the capital is done, and capital moves very slowly.

When confronted with the complications of navigating the unwieldy terms of city bureaucracy, organizations are often forced to take cost-benefit approach to determine whether a collaboration is worthwhile. Esther Robinson, Co-Executive Director of ArtBuilt, shared her approach, saying, “I like to think about things in terms of the economic concept of opportunity cost. We could measure the opportunity costs of lost time working in the community, and opportunity costs globally around applying, reporting, and paperwork.”

Conclusion

Learning exchange participants concurred that through the relationships, networks, and common experiences shared at the gathering, we can put our heads together to foster increasingly creative collaborations with city government.