Illustration by Donovan Vim Crony for Mirror Memoirs

Editor’s Note

__

Mirror Memoirs is a national storytelling and organizing project intervening in rape culture by uplifting the narratives, healing, and leadership of LGBTQI+ Black and Indigenous people, and other people of color who survived childhood sexual abuse. In early 2016, Amita Swadhin assembled an advisory board of LGBTQI+ survivors of color, created research questions, and set out across the United States to interview survivors at this intersection, ultimately recording sixty audio interviews across fifteen states. We asked them to reflect upon their journey and their plans for the artistic components of the work intended to engage the public. We also asked them to share what these interviews reveal about how traditional reliance on state institutions and carceral solutions actually perpetuate harm to survivors, while doing little to address the root causes of rape culture.

When I began my Masters in Public Administration program at NYU in 2008, I knew I wanted to return to my earliest professional work, focused on ending child sexual abuse and family violence. So I did what any public policy student would do: I started going through the statistics again. The research around the neurobiology of trauma and the long-term health effects of childhood sexual abuse has really advanced over a decade. While I was in grad school, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a study showing gender nonconformity was a risk factor for child sexual abuse. The main data sources for child sexual abuse are from very mainstream places like the U.S. Department of Justice and the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Yet, we don’t see organizing campaigns from billboards, and public service announcements, and podcasts, and television shows, and paintings, and cultural interventions that you would expect with any other pandemic. During this time of the coronavirus pandemic, I’ve really come to use the word pandemic to talk about childhood rape, because the CDC conservatively estimates that 20% of Americans are survivors. The rates are even higher in several other countries, again based on government studies. For instance, in my ancestral homeland of India, the rate of survivorship is 1 in 2 children. What other public health issue can you think of that affects that many people, yet we don’t have any kind of public messaging around? I can’t really think of a single one besides childhood sexual violence.

I started thinking about why that was. With childhood sexual violence, there’s no lack of data. There is actually just a lack of cultural ease in naming the violence beyond the media’s long history of sensationalizing individual cases. If you only studied media reporting of child sexual abuse, you might think it was just a smattering of unconnected dots, with no structural or historical context at all. That’s not the reality, so I realized that we needed a mechanism that would help people understand the collective, systemic, historical and cultural nature of this violence. Individual survivors needed to tell our stories in a way that could still allow us to be in control of the narrative, and not have to go through the terrible mainstream media machine that too often propagates rape culture.

I knew Ping Chong and Company’s theater program Undesirable Elements dealt with really difficult subject matter in a way that was not extractive. A play is developed and performed by an ensemble that shares an experience. It’s not about one person’s story. There’s no superhero, there’s no pedestal, there’s no super victim. I met with assistant director Sara Zatz, and she agreed to hire me to create a show that used the experience of adult survivorship of childhood sexual violence as the common thread. We co-facilitated three weekends of writing workshops and theater games that led to the creation of the script of Secret Survivors. The show ended up being a cornerstone of a huge philanthropic initiative by the Novo Foundation to create some of the first funded programs lifting up survivors of color who were doing work to end child sexual abuse. In 2015, I got a phone call from someone who was affiliated with the Novo Foundation explaining that they were starting a new program specifically for people of color who are childhood sexual abuse survivors and who are doing work to end child sexual abuse called the Just Beginnings Fellowship. And that’s what led me to create Mirror Memoirs.

Individual survivors needed to tell our stories in a way that could still allow us to be in control of the narrative, and not have to go through the terrible mainstream media machine.

I was publicly out as a survivor as a college freshman because I worked at the women’s center. Because this is a global pandemic that nobody knows how to talk about, except in maybe secret corners or in private therapy, a lot of people on campus started disclosing to me. So by the time I was casting Secret Survivors, I already knew a number of people who were child sexual abuse survivors, all of whom were either artists or social justice organizers in New York City. And by 2009, all of us had already individually developed the politics of prison abolition. That was really important to me in the original show because state violence was a big part of my own survivorship narrative. When there was state intervention in my life at age 13, the social workers, and prosecutors, and police officers were all white people who either threatened to prosecute my mother or responded with very racist white savior narratives and untrue assumptions about Indian American immigrant communities.

The state mandated me to go to group therapy when I was 16 for an entire year with other teenage girls who were incest survivors. The youngest girl there, Pauline, was 13, in foster care, Indo-Guyanese American, and really struggling with suicidal ideation, because she had been harmed by so many men by the time she joined our therapy group. After a few months, she was institutionalized in the county mental health hospital, where she was harmed again by one of the hospital workers, and she ended up taking her own life. She was the second child in six months to take their own life at that same hospital. So I already also had a very personal awareness that the state sanctioned perpetration against children. I have since learned that it’s very common for children of color, queer children and trans children, especially those who are wards of the state, to experience sexual assault at the hands of hospital workers in those facilities. And it was really important to me in building Mirror Memoirs that we highlighted that reality even more deliberately than Secret Survivors had. Mirror Memoirs has deliberately and unapologetically been an abolitionist project from the beginning.

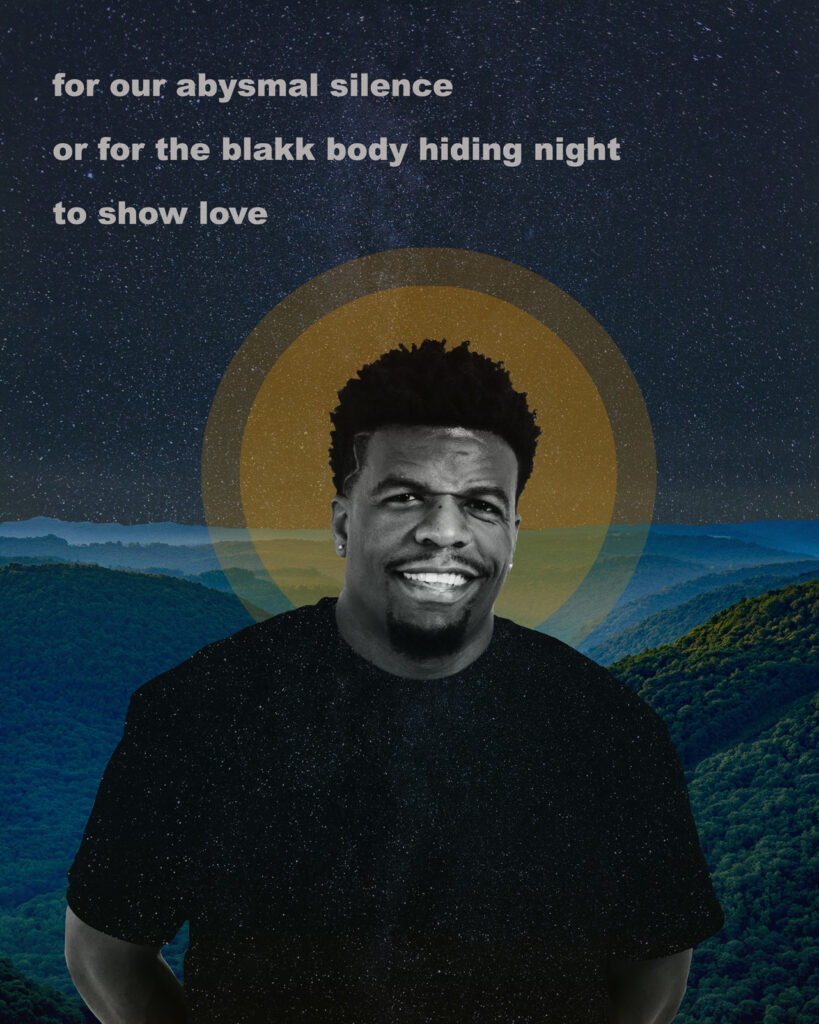

Photo collage of Mirror Memoirs project participant Tim’m West by Mer Young.

One of my aims with the project was to highlight how much the state sanctions perpetration and even fuels it by many different agents of the state—not only workers in psychiatric institutions, but workers in group homes, foster care families, police officers, and guards in juvenile detention centers. Also studies show that specifically male-assigned-at-birth children who were gender nonconforming in any way were the most at risk. They were six times likelier than children of any other gender to experience rape or sexual assault, so they should be the face of and comprise the bulk of decision-makers in an emerging movement to end sexual violence. But that is absolutely not the case, so Mirror Memoirs aims to center transgender, non-binary, intersex, and gender nonconforming male-assigned-at-birth people. The project also centers Black and Indigenous people, because this country was established through the rape of enslaved Black and Indigenous children, as is well documented, in California Catholic missions, Native boarding schools, and southern plantations. With that goal in mind, I put a board together of people I had long-standing relationships with, all of whom fall under the umbrella of LGBTQI+ BIPOC people who survived childhood sexual abuse. They helped me shape this organization from the beginning. They helped define the research questions. They also helped me structure our strategic priorities, once I realized this was going to be more than an audio archive. I recently named a co-director, Jaden Fields, a trans Black man who is a survivor of childhood sex trafficking and other forms of childhood sexual violence. We currently have a fundraising campaign to fund his position, if people wanted to contribute to that.

From the initial sixty interviews, I learned a lot about how sacred it is—and also how treacherous it can be—to hold that kind of space for people, many of whom have never had the privilege of therapy before. These are many people who are severely under-employed or unemployed, many people living with trauma-related disabilities and chronic illnesses, many folks who face anti-Blackness and white supremacy and transphobia, and are kept out of the formal workplace for those reasons. For many folks, I was the first person they talked with about details of what had happened to them. And that requires a lot of care, not just for the other person, but for myself as a survivor, because I’m obviously a subject of my own research as well. I’m now training people who have told their stories in the project to record more interviews and deliver educational workshops and keynotes, becoming what we now call a core member. Core members also get a say in shaping the direction and form of our organization. It’s been kind of a beautiful but humbling experience to also receive the kind of mutual aid and collective care from the membership base that I am holding space for and creating a container for. I am a part of this membership base, and that shows up in my own life all the time.

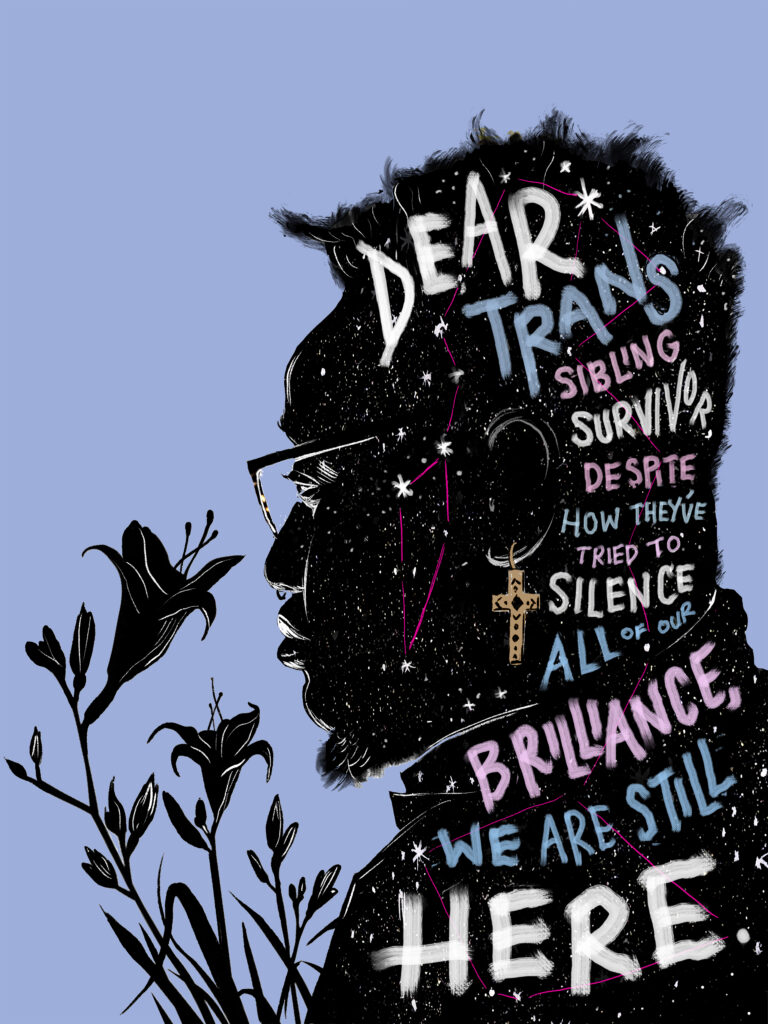

Illustration of Jaden Fields by artist Jess X. Snow.

Looking forward, in fall 2020, we are putting our efforts into creating some toolkits under certain themes: What do we do with the people who commit child sexual abuse if we have an abolitionist politic?; What’s the vision for healing and the world we want to live in?; and specific Black experiences within the Mirror Memoirs archive. In terms of the art components, I have a big vision that includes everything from animated videos, to another theater project that is focused on male-assigned-at-birth survivors, to a multimedia art exhibit, and poetry readings. In spring 2021, the plan is to release our audio archive. We have worked with a comic book illustrator, Donovan Vim Crony, to create 15 portraits of the folks who chose to stay anonymous in the archive and we have a photo collage artist, Mer Young, who is still creating some of the beautiful portraits of people who are publicly coming out. Artist Jess X. Snow is starting to envision artistic representations of people’s answers in the interviews. We plan to use these images as cover art for audio toolkits and as art products to become a fundraising mechanism for our work to be more self-sustaining.

The art component feels really important because what Secret Survivors taught me is that whether or not you are a survivor, everybody is raised in rape culture that enables a global pandemic of children being raped. And so it is the job of the artist in this case to help people see the water that we are swimming in. Listening to Mirror Memoirs stories is like taking the red pill in [the movie] The Matrix—suddenly you can see the reality of the rape culture that we are all swimming in, and that can be a very overwhelming experience. The fact that we are all socialized to know how to attend the theater, or visit an exhibit, or bear witness to a poetry reading, or sit in a circle with each other, makes it a little bit less horrifying when you have that moment of awakening to the reality of the violence that we are within. That’s the power of art.

For survivors in our healing circles and convenings, the power is in being able to come together with 30 other people to listen to each other’s stories, engage in somatic theater games, and do some visioning about the world we want to live in. People got so delighted by having this permission to just focus on their own healing. We have to learn how to be playful with each other, even when it is about something that can be so despairing. Part of my impetus for creating any of these projects was that so many people were disclosing to me when I was a young organizer in New York City, but never telling each other. I wondered how much stronger our movements could be if we had a more holistic compassion for the entirety of what we have each survived? Then people could depend on one another for things that perhaps they were forcing themselves to try and weather alone before, like a panic attack, an anxiety attack, or a trauma-related flashback. The healing needs to come in intimacy and connection because the violence happens in isolation. I think there is a particularly beautiful kind of art in weaving connections between people and allowing for that social fabric to be woven where only isolation and wounding existed before.

There is a particularly beautiful kind of art in weaving connections between people and allowing for that social fabric to be woven where only isolation and wounding existed before.

Finally, Mirror Memoirs complicates the story about who does the harm. It’s really important to note that most people who are raped as children do not go on to rape other people, but of the population of people who do, a large majority of them were raped themselves as children. The second phenomenon that comes up in our archive, is that of the small percentage of cases that actually do go through the criminal legal system, 40% of known cases are juvenile to juvenile. So we have a large number of children who were raped or sexually assaulted, and then in their trauma reaction, go on to commit sexual violence against a younger child while they are still themselves a minor. A third phenomenon is that 9% of our survivors were raped or sexually assaulted as children by cisgender women, but that is hardly ever talked about in public discourse. Even in this #MeToo era, there is a uni-directional arrow of harm that is talked about from cisgender men and boys towards cisgender women and girls. And that’s just not the reality of how this violence happens. That’s why I think the majority of the members in Mirror Memoirs are advocating for something different than the legal/carceral system on offer today. Some people use the words “transformative justice” but other people say, you know, “I wish that the person who harmed me could get the help that he or she needed because clearly they were really wounded if they could hurt me that way. I want them to never do this to someone again. I want them to have to declare what they did in a community that’s going to see them and witness them—and not dispose of them—but actually hold them accountable.” And that’s tricky, because we are only taught how to punish each other and then dispose of one another. If you want to live into a world in which people heal and transform, then that means you need to stay in relationship with them. To be clear, I don’t mean the survivor who was directly harmed, but someone needs to stay in relationship with them, who knows what they did and can still see their humanity.

We are only taught how to punish each other and then dispose of one another. If you want to live into a world in which people heal and transform, then that means you need to stay in relationship with them.

Mirror Memoirs is partners with the Ahimsa Collective, which is another survivor-led organization founded by Sonya Shah that holds restorative circles in prisons where cisgender men who have committed sexual violence, including childhood rape, go through an accountability process over a year and a half. I have attended two of those circles along with some of my colleagues, and it’s really powerful to recommit to the actual practice of abolition when you are literally sitting in a circle, and shaking hands, and sharing meals, and spending eight hours with men who are looking you in the face and saying, “Yeah, I raped a child.” And also, “I was raped as a child, and I never got help, and I never had a place to talk about it until I opted into this voluntary program, years into my sentence.” In order to end child sexual abuse you have to completely remake the society that we are living in, and the way that we are living with and responsible for one another.

EXCERPTS FROM THE MIRROR MEMOIR ARCHIVE

Illustration of Rio by Donovan Vim Crony

If you went through a portal into another dimension in which capitalism does not exist, and your only responsibility, from the moment you wake up to the moment you fall asleep is to heal yourself, and you have a bottomless toolbox with every material and spiritual resource you need to support that endeavor, what’s in your toolbox?

“The first thing I think is that I want to live in a house with a lot of windows and sunlight. The house I grew up in as a child was very small, and was not safe to live in, so where I live is very important to my healing. I currently live in a studio with one window and it’s very dark and gloomy and small, and I hate it. And so that’s the first thing I need: a place I feel safe and happy to live in.

My next thought is the work I want to do with adults who are perpetrators and survivors of sexual violence, survivors of child sexual violence specifically, but perpetrators of any kind of sexual violence… In the past week, I’ve been admitted and received a scholarship for a grad school that I really want to go to, and I’ve been imagining this center where clients would feel welcome and safe to come in. With access to food and employment opportunities—you can’t do any kind of healing work when nothing else in your life feels safe and you lack access to basic necessities like something to eat and somewhere to be able to be warm, if it’s cold outside… I think that there’s not enough emotional energy to go around. Doing this kind of work takes a lot out of people, and it’s very frustrating. I go back and forth between hating my father and wishing that he was dead—I’ve moved away from that, but that’s initially where I was during the initial stages of my healing—to now, I wish that he wasn’t in prison, and I wish that he wasn’t going to get deported. And I wish there was a place for him to go to sit with someone who cares about him, to ask him what went wrong in his life and what he needs. [Pause]

When I think about my father’s story, I know that he was a very smart person, but he was also pushed out of high school. He never finished high school. When he transferred schools from New York to California, the registrar at his new high school in Los Angeles told him that his files didn’t transfer, and she kept telling him this. But when he dropped out of school, he went to pick up all of his records and his file was very thick with all of the copies of the records that had been sent over, because this woman had been lying to him, saying his records weren’t there. And he destroyed the office, he flipped over desks and was very angry, because his education was taken away from him. And so, I think of my father, I think of someone who is very hurt and sad and didn’t have anyone in his life to support him or take care of him. When I’m trying to imagine this center that I eventually want to open, I think of my father, and I think about what would he have needed when he was a child; when he was a teenager; when he was an adult that would have made his life happier.”

— Rio, a Latinx, queer, non-binary, Mirror Memoirs project contributor

Photo collage of project contributor Bianca Laureano by Mer Young

What’s your personal vision for how humanity can end child sexual abuse?

“The first thing that comes to mind immediately is, this conversation about epigenetics, which is really popular—how we carry trauma. What that tells me though is that, “Okay, if I have trauma in my genetic makeup, that also means that I have liberation in my genetic makeup,” and so how do I tap into that? How do I tap into the parts that aren’t always the traumatic part that people always want to focus on? What will that look like over a generation? If we do this work now and are able to impact the people in our lives who are having babies, who are raising children in whatever capacity, we can really help shift that. Because how amazing if in twenty years the headline is: “Epigenetics, We’re All Wired for Liberation and Freedom and Victory.” That to me is a success. Just emancipating ourselves from these ideas that we’re constantly carrying all these negative things, and we’re made up of this negative stuff or these negative experiences.

I don’t know, maybe it sounds really woo woo, witchy or whatever, but also this larger collective divine power. I don’t know where it comes from, I don’t know where it stems from, but we all have it. And really doing the work collectively. Just like you said, intergenerationally, I feel like transnationally— just worldwide. It’s totally possible. Especially as children of migrants or immigrants, we can also take this back to our homelands or to the rituals that we have in our lives and the ways that we talk about it. So that’s really exciting for me too.

I think also having more open conversations, just wherever we are. Whenever I’m out with friends, I do a lot of sex coaching over a meal or whatever, there are other people who listen in and can maybe hear some things. I would love to normalize that conversation where we can say “childhood sexual abuse,” we can say “rape” and “incest.” We can say all the words that we need to, and not whisper it. So the people who hear it, they can just be like, “yeah” and it not be this foreign, shameful thing. Instead, it can be like, “That was an injustice, and we’re all collectively invested in ensuring that doesn’t happen again,” and “What do we need to do?” So really, a community response, at the end of the day. What’s a community response to childhood sexual abuse? Because it’s gonna be the people who do it, not just one individual or some policy or whatever.”

— Bianca Laureano, Mirror Memoirs project contributor

Amita Swadhin is an educator, storyteller, activist, and consultant dedicated to fighting interpersonal and institutional violence against young people. Their commitments and approach to this work stem from their experiences as a genderqueer, femme queer woman of color, daughter of immigrants, and years of abuse by their parents, including eight years of rape by their father. They are a frequent speaker at colleges, conferences, and community organizations nationwide, and a consultant with over fifteen years of experience in nonprofits serving low-income, immigrant, and LGBTQ youth of color in Los Angeles and New York City. Amita’s writing has been featured on The Feminist Wire and The Huffington Post, and in the anthologies Dear Sister: Letters from Survivors of Sexual Violence (AK Press, 2014) and Queering Sexual Violence (Magnus Books, 2016).