A Maskoke child holds tomatoes grown in the Ecovillage greenhouses. Residents grow vegetables based on the traditional diets of their ancestors. Photo courtesy of Marcus Briggs-Cloud.

The organization Ekvn-Yefolecv [ee-gun yee-full-lee-juh, a double entendre meaning Returning to the Earth/Returning to Our Homelands] is a Maskoke collective committed to embracing the role of protecting and reviving traditional relationships to the earth while revitalizing language and culture.

I used to think that the most critical issue Maskoke People face was language loss as our ancient, yet threatened, language was projected to fall silent by the year 2040. I thought language revitalization was the sole work to be done to restore wellness among our Maskoke People. That monolithic thinking came to an abrupt halt upon awakening to the reality that efficacious language revitalization work is contingent upon numerous interconnected factors that address systemic issues through a holistic lens. In order to see a real reversal of language loss, we have to altogether change the way we live.

The journey goes something like this, I wanted to see my language survive and went from thinking that teaching words for animals, numbers, and colors (like the methodology of most community-based endangered language programs) was actually making an impact, to then thinking that teaching in the university system in Oklahoma was going to be the successful avenue to revitalize Maskoke language, to then realizing that I didn’t even have a goal or expectation to know how to assess what success would look like. It took a little time to sort through the many band-aid options but with the Maskoke language on the brink of extinction, I began to promote the message that there should be only one goal to which we aspire in language revitalization work—that is, to grow new fluent speakers!

In order to see a real reversal of language loss, we have to altogether change the way we live.

The Indigenous Language Institute estimates only 20 Indigenous languages will still be spoken (in the U.S. context) by the year 2050. It might seem like an elementary concept that the foremost goal of any language program is to grow new fluent speakers, but the reality is, such a goal is actually seldom established. I noticed that when I spoke my own language, it was standard practice to insert English words amid a sentence for lack of not having that particular term. Since my elders did it, I mirrored their example. After all, it seemed inevitable to speak Maskoke with recurring English usage due to the remarkable amount of time we interface with the English speaking world. I also began noticing that language immersion programs globally were addressing this pervasive issue of obsolescence by importing nouns/concepts from the settler-colonial society around them and crafting new words to convey those nouns/concepts. Initially, this seemed like a worthy practice, but I started thinking more critically about this. In my own Maskoke context, by the time we import into our lexicon 3,000+ words that are inherently premised on post-industrialization capitalist ideology, we’ve deviated significantly from the unique bio-regionally derived traditional ethos that our ancestors left to us in the first place. We would find our Indigenous ontological worldview, that is inextricably tied to the natural world, flipped upside-down. Therefore, such a practice begs the question, “Why not just speak English?”

In our Maskoke medicinal traditions, practitioners sing prescribed formulas in our language and blow into plant concoctions, which results in an efficacious healing substance to be consumed by members of the ceremonial community. These medicine traditions are required components of Maskoke Posketv (often referred to as Green Corn Dance) ceremonies which renew our relationship to the natural world around us. Our prophecies tell us that if we cease conducting our Posketv ceremonies, thereby allowing our sacred fires to go out, Maskoke People will perish. No language means no ceremony; no ceremony means Maskoke People will perish. So, ultimately the silence of the Maskoke language equals the disappearance of Maskoke People. Both accommodating the settler-colonial apparatus by inserting so much English amid Maskoke sentences, and the alternative option of composing an abundance of new vocabulary to dump into our lexicon felt like an unjust compromise of our indigeneity. I started thinking more radically about a theory of change. It became apparent that we would have to recreate the society in which our language once historically functioned best, which was, unsurprisingly, a society premised on intimate relations with the natural world. From this consciousness emerged the vision to build an ecovillage.

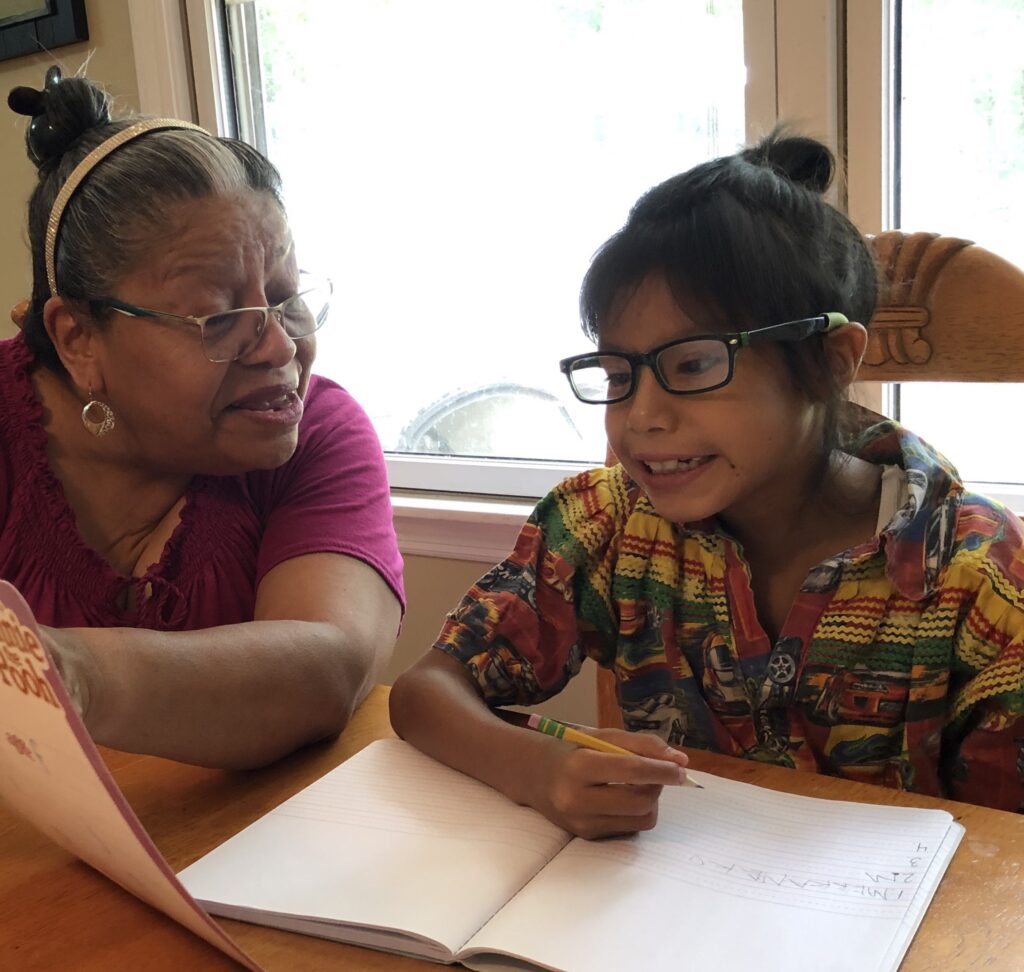

To grow new generations of fluent Maskoke language speakers, no English is spoken in Ekvn-Yefolecv’s language immersion program. Photo courtesy of Marcus Briggs-Cloud.

Our ancestors were forcibly removed from what are colonially known as Alabama and Georgia today, to lands 700 miles away in what are colonially known today as Oklahoma and Florida. It became spiritually evident that we needed to assemble an intentional community of like-minded Maskoke folks who are products of forced removal to return to our homelands for the purpose of committing to both biophysical and ceremonial stewardship of the land our ancestors cared for since time immemorial. Cultivating a vision for a decade and then searching and praying for the most appropriate parcel of land for another five years, Ekvn-Yefolecv closed on 600 acres of our traditional homelands on January 12, 2018. It is an indescribable feeling to once again reside in the world that our ancestors inhabited.

As we were traditionally an agrarian society, our contemporary society must be centered on agricultural practices in order to provide the host activities for our ancient lexicon to thrive in the most authentic Maskoke way, and more notably to augment the ability to engage agriculture in culturally competent ways. Critical linguistic analysis of Maskoke language enables us to extrapolate the traditional epistemological worldview that our ancestors left to us (as it is intact in the language’s grammar), concerning appropriate ways in which we are to interact with the natural world. It establishes an ethic that constrains our ability to participate in the commodification of Earth, at least when speaking Maskoke language. In other words, we are forced to resort to English language practices to articulate such environmentally exploitative and extractive activity.

Considering Indigenous language revitalization work then must not contribute to ecological destruction, our community had to start thinking about how we build this ecovillage in non-extractive ways. For instance, our language immersion program, wherein no English is spoken, requires a decolonial lens that penetrates our tendencies to adopt conventional ways in which we school our children—such as not building lesson plans around disposable materials that are only fun for 20 minutes but end up in a landfill shortly thereafter; contributing to methane gas emissions that warm the planet. Additionally, elder language bearers that have diabetes and hypertension do not feel like interacting with many folks when struggling with their sicknesses. Thus, decolonizing our diets became imperative, though this has not happened without resistance from our elders who love soda pop and spam! And, not without working with a dietician for several months to learn how to cook for persons with chronic illnesses and learning to tailor recipes to traditional foods that we can grow and for which we forage. These are learning curves, as we are having to slowly reclaim traditional knowledge from various sources. We are also learning what it means to eat “traditional foods” in an era of climate crisis wherein our food choices also impact all Peoples’ livelihoods. This causes us to reflect on what it means when we say vnokeckv etemocet fullēt owēs, “we going about having love for one another” to extend to all Peoples, especially the most vulnerable Peoples of the planet.

It is an indescribable feeling to once again reside in the world that our ancestors inhabited.

We are regularly discerning ways in which we can walk the talk! For instance, we have to: remain conscious of what kind of decolonial language curriculum to build from scratch for our students (across age groups); design and implement regenerative agricultural practices; explore ways to ensure many forms of health for ecovillage residents; develop plans to reduce ecological footprint; generate revenue from non-extractive economy-based ventures so the ecovillage can be sustained; navigate and maintain harmony among diverse personalities—including traditional conflict resolution mechanisms to retain ecovillage population; overcome lateral oppression; learn natural building construction; relearn the ecology of our traditional homelands; try to piece together our traditional canon of stories that provide the foundation for understanding significant ecological places/spaces/species; and the list goes on. Simply trying to save a language from extinction has necessitated the creation of a new society. We are not so naive as to believe that our ecovillage is somehow exempt from globalization or climate crisis, but it is just insular enough to retain our language and culture with exponentially more integrity than we’ve had the chance to do since we were displaced from our traditional homelands 182 years ago. We can once again be full-time Indians instead of having to schedule our time to be Indian over the weekend at a ceremony.

Ekvn-Yefolecv rejects capital and material accumulation and is an income sharing community wherein residents receive a modest stipend for performing rotating duties, in addition to receiving a timber-framed tiny home for residence. The entire world must learn to slow down and simplify human lifeways. The objective is not to return to a Clovis Indian era of living, but rather incorporate sustainability technologies that provide a good quality of living while demonstrating reverence for Earth and all living beings. Green technologies alone are not the answer, rather, it must be coupled with an entire lifestyle draw-down. As we were compiling an energy budget, it became apparent that certain technologies would not be possible to deploy. For instance, some residents of Ekvn-Yefolecv formerly enjoyed using an instant pot to cook with, but an instant pot requires 1000 watts to run a 20 minute session. The typical settler-colonial mainstream response is, “How many more solar panels will we need to run the instant pot and toaster and…?” Our response is simply, “We don’t need an instant pot or toaster or…!” This is all part of slowing down our lives, which makes us open to the medicine to grow stronger in our lives. Cutting firewood to operate a rocket oven or rocket mass heater is more time consuming than turning on a grid-tied thermostat, but the rocket mass heater is much more energy efficient—so it’s good to Earth. Moreover, one burns lots of calories and strengthens core muscles by harvesting firewood and splitting it. We have adopted timber-framing construction because it coincides with our philosophical values, such as minimal embodied energy requirements in fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Felling, skidding, debarking, and milling the timbers is performed by ecovillage residents. Slowing down also requires stewardship of the land and restoration of regional animal populations such as the buffalo and lake sturgeon. The implementation of holistic management with the buffalo through rotational grazing is labor intensive and requires an intimate relationship and trust with the buffalo as opposed to conventional farming practices that lead to soil degradation. We are working to restore a threatened fish species that is sacred to our People, the lake sturgeon, in the watershed from which it was extirpated in the 1950’s due to the erection of hydroelectric dams. All of these aforementioned practices require a lot of work and a lot of time, but that also means less time to participate in capitalist-consumerism. It is also what is necessary, in a spirit of reciprocity, to be in good relationship with the natural world.

In twenty-five years, Ekvn-Yefolecv Maskoke Ecovillage will be the only place on the entire planet where one can go to hear the Maskoke language spoken fluently.

All buildings in the Ecovillage are timber-frame constructed to uphold the community’s values in reducing its carbon footprint. Photo courtesy of Marcus Briggs-Cloud.

Admittedly, minimalist living, income sharing, cleaning composting toilets, swimming with sturgeon, and inhaling bison breath all sound like utopian lifeways, but engaging Maskoke folks in this project has not been without immense ambivalence. Some community members have wrestled with a difficult-to-identify issue that even though the philosophy all sounded “right,” their apprehensions were emerging from correlating such a lifestyle to impoverished living conditions in their childhoods. We were all taught to pursue the American capitalist dream. Recognizing that the ecovillage lifestyle may be simple and associated with living “poor,” a number of Ekvn-Yefolecv residents have decided that because they have agency in living this way, and see the genuine quality of life in this paradigm, they have actually come to perceive it as legitimate liberation from oppression.

All this is to say that if one wants to revitalize Maskoke language, not only do you have to speak to children exclusively in the language (NO English) from their pre-verbal stage onward, you also have to: know how to grow beets and native pumpkins for community health and save seed; generate revenue from regenerative practices; clean poop from a bucket instead of wasting potable water to send your poop to an unknown place; toast acorns you harvested in the woods with little kids on a rocket oven that required you to cut wood from the forest; mourn the loss of a sturgeon when she passes and honor the sturgeon with a song each time you harvest one to nourish an elder language bearer; cease mansplaining; quit buying frivolous plastics; turn to the sun each morning and give thanks for the day and for its energy to power your LED lights; and, most importantly, cultivate tons of love and compassion! In twenty-five years, Ekvn-Yefolecv Maskoke Ecovillage will be the only place on the entire planet where one can go to hear the Maskoke language spoken fluently. Through this holistic paradigm, we project that in two generations, having raised children as full-time Indigenous People, Maskoke language will be the primary language spoken at Ekvn-Yefolecv Maskoke Ecovillage. Residents will be spiritually and physically healthy persons who inherited a resilient non-extractive, small-scale society in the midst of climate crisis. We hope to serve as a replicable archetype for other communities to implement in their own contexts premised on intimate relations with the natural world, where our unique languages and cultural lifeways thrive once again.

Marcus Briggs-Cloud (Maskoke) is a language revitalizer, scholar, and musician. He is co-director of Ekvn-Yefolecv, an Indigenous ecovillage community in Weogufka, Alabama comprised of Maskoke persons who have returned to their ancestral homelands to practice linguistic, cultural, and ecological sustainability. He is a graduate of Harvard Divinity School and a doctoral candidate in interdisciplinary ecology at the University of Florida where his work intersects liberation theology, linguistics, ecology, race, and gender identity. He received two Native American Music award nominations for his Maskoke hymn album Pum Vculvke Vrakkuecetv (To Honor Our Elders) and served as composer and choir director for the liturgical canonization of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha by Pope Benedict XVI. He is partnered to Tawna Little (Maskoke) and they have two children, Nokos-Afvnoke and Hemokke, with whom Marcus enjoys speaking exclusively in the Maskoke language.