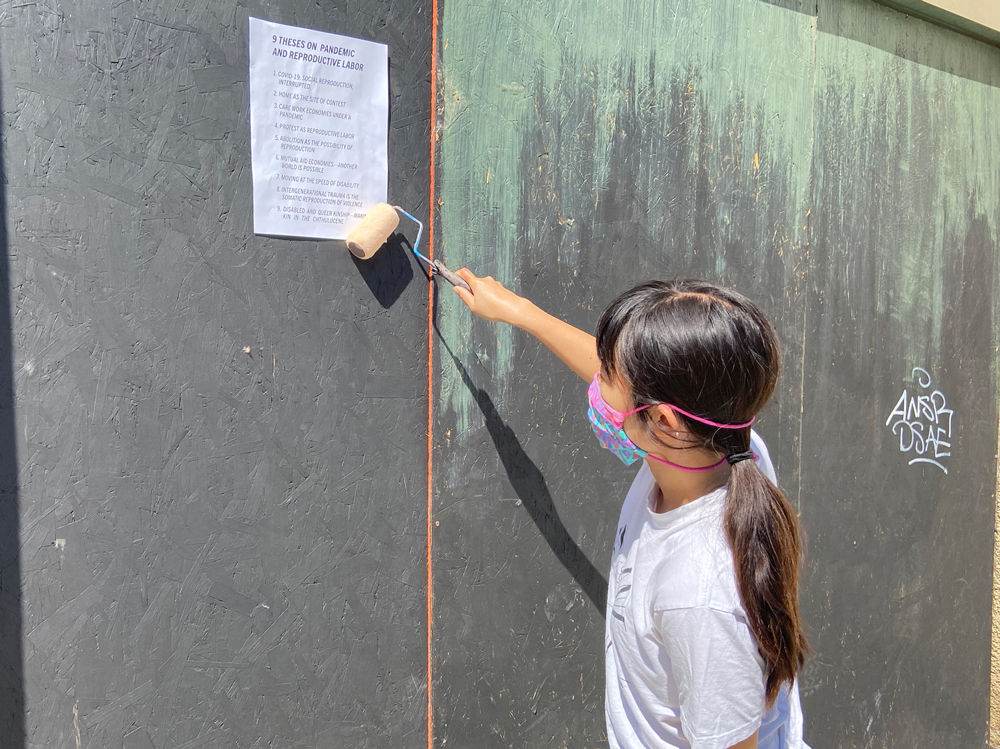

Artist Carol Zou. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I. COVID-19: Social reproduction, interrupted

What day is today? Right now, during a global pandemic, time doesn’t matter so much, as hours melt into days melt into what feels like years of wondering when lockdown will end. But time might matter in October 2020, when this essay finally reaches publication, and COVID-19 exists somewhere on the continuum between a continuing terror or a quaint memory, and this essay exists somewhere on the continuum between prescient or total, absolute, bullshit. We are all bound by our time.

What day is today? Today, 112,433 people have died of COVID-19 in the United States. Today is the eighteenth day since protests in Minneapolis over the police killing of George Floyd sparked a nationwide movement of uprisings against police brutality. Today is the eighty fifth day since the City of Los Angeles announced shelter-in-place in response to COVID-19. Today is the forty fourth day since I’ve passed through an airport, decontaminated myself upon landing, and cried. Today is a Friday.

Today I take up the task of making sense of the reproductive reorganization of society ushered in by COVID-19. Today.

II. Home as the site of contest

“Stay home,” the CDC says, when Black people have been historically disenfranchised from homeownership through redlining, when millions lost their homes in the economic crash of 2008, and when millennials like me eat too much avocado toast to ever dream of homeownership. “Stay home,” the CDC says, while thousands of unhoused people live on the streets in the shadows of empty hotels and luxury lofts. “Stay home,” the CDC says, when a one-bedroom in Los Angeles costs three weeks of work at California minimum wage. “Stay home,” the CDC says, as domestic violence rates surge worldwide when survivors cannot leave their abusers. “Stay home,” the CDC says, while the government ignores calls to cancel rent so that we can, in fact, avoid eviction and stay home.

Home is the site of contest for a pandemic whose response necessitates staying home. Home is political as fuck. Stay home actually means, stay political as fuck.

III. Care work economies under a pandemic

Care work under a pandemic is both acutely highlighted and invisibilized. Widespread death can only be countered with widespread care. The workers responsible for mending society during this crisis are either care or maintenance workers: grocery workers, sanitation workers, nurses, doctors. At the same time, care work has shifted from its paid position in the economy—a paid position that feminist and care work advocates have advocated for1—back into the unpaid domain of the home. Parents are now expected to work full time as well as play the role of stay-at-home schoolteacher. An unpaid labor force of predominantly women are sewing masks to make up for the lack of preparation by the federal government. People are baking a lot of bread.

Care work once again is expected for free, and I worry that we will actually lose whatever little ground we’ve fought for in making the work of motherhood visible. I’m a little mad at care workers who are not going on strike right now and refusing their multiple roles of caretaker, teacher, and full-time worker. But I’m madder that our general conception of the strike still exists within an Industrial Revolution-era fantasy of organized workplaces, when most of us exist within the late capitalist reality of working from home, working within the gig economy, and unremunerated care work.2

As we consider the conditions for economic recovery during a pandemic, I wonder: How can we reorganize our economy around slowing the pace of hypercapitalism that was already killing us and the planet? How do we not create more jobs, but perhaps, fewer jobs for people juggling 4 different gigs to survive? What if we recognized the invisible, unpaid work in society such as placing a paid caregiver with every family that needs caregiving support? What if we created economic structures for paid rest such as employing people in six month “second shifts” for certain frontline positions so that frontline workers could take a break? What if we trained and paid people to hold space, listen, coregulate, and otherwise attend to the mental health needs of their community during this time and after?

We’re all working too much right now and having too little of it economically recognized as “work.” How do we not “go back to work” but recognize and support the ways that we are already working?

IV. Protest as reproductive labor

If we understand reproduction as the possibility and survival of the next generation, we will soon realize that there are those of us who were never meant to survive. That to reproduce a next generation, we will need to define reproductive labor as more than just nursing an infant and changing their diapers until they reach adulthood. What does it mean for a Black or brown child to be raised to reach adulthood in a world in which communities of color live in segregated neighborhoods with poor access to food and with poisoned air, water, soil? A world in which police roam the streets and the schools in an open act of war against Black and brown people?3

Protest is reproductive labor insofar as it creates the conditions for those of us who were not meant to survive, to live another day. Protest recognizes that white supremacist capitalism is a death cult and protest says let us rupture our reality so that we may live.

Confined to our homes for months, it’s no wonder that we in the United States have erupted in protest over state sanctioned killing of Black people. For reproductive labor requires time and space much as all labor does. The traditional capitalist work week leaves no time for contemplating the death structures4 of society and how they might be changed. It is only through a catastrophe of unemployment, or withdrawal from the formal labor economy, that we are finally able to turn our attention to the labor of transforming society. Is protest the social reproduction strike we have been waiting for?

V. Abolition as the possibility of reproduction

Abolition, then, is a disinvestment from the necropolitical machinery of the state, and an investment in the conditions of life.5 COVID-19 does not discriminate, but our state structures do when it comes to who can access medical care, who is still required to go to work, who experiences the rapid spread of COVID-19 behind bars, and who experiences the rapid spread of COVID-19 when the state calls in a militarized police force to kettle protesters instead of letting them go.

Abolition is about more than defunding the police. Abolition is about investing in the social reproduction structures of society—education, physical and mental wellness, economic stability, community resilience.6 Abolition is a vision that reorganizes what we have come to understand as safety and what we understand to be social divisions of labor. Everyone can, and should be an abolitionist.

VI. Mutual aid economies—another world is possible

We are figuring out what our institutions cannot. I have watched artists figure out how to create supply chains for face masks and face shields7 with more effectiveness and fewer resources than Jeff Bezos. Faced with images of farmers dumping mountains of potatoes due to the breakdown of trucking systems, we are learning how to grow our own food. Somehow, despite the highest unemployment rates since the Great Depression, we have raised millions of dollars for bail and emergency relief funds.

In some ways, I do think that we are learning what truly constitutes essential labor, and what does not. May the labor that you are performing right now during the pandemic be considered the most essential moving forward.8 In addition to the labor of essential workers on the frontline, may we hold these acts of checking in our neighbors, creating systems of local support, growing food, reading Ursula K. Leguin,9 sitting still with our feelings of unease, as essential.

The world is on fire, and we are also creating the world that we want to rise from the ashes. The Brooklyn Museum has become a food pantry during the pandemic, and to be honest, I hope every large arts institution that furloughed their workers and was inaccessible to communities of color and poor people becomes public bathrooms for protesters, shelters for unhoused people, daycares for working women, emergency medical centers, community gardens, and more.

VII. Moving at the speed of disability

Most days prior to the pandemic I was a depressed human trash can, and still am one. I’ve spent years fine-tuning my life to accommodate my bouts of clinical depression—remote contract working, working at odd hours of the night, neurotically stocking my pantry with non-perishables, amassing a wide range of Instant Pot recipes that require 5 minutes of physical effort,10 and cancelling or rescheduling meetings because “emotions,” aka hours spent in bed wrestling with thoughts of suicidality.

Now almost everyone is on depression time. Almost every remote work call begins with a fifteen minute debrief of how the pandemic is touching us today, a mini-therapy session before we halfheartedly reprise our roles in a matinee performance of productivity under capitalism. Almost every remote worker is working odd hours and cancelling meetings because of extenuating circumstances. Projects move at the speed of molasses, or at least the speed it takes for someone to will themselves out of bed, confront the immense anxiety of living in a dying world, attend to work, and repeat.

Yes, it does suck to get a taste of my own medicine. I suppose I’m sorry for all the times I used to flake out and procrastinate on deadlines. But I’m also not sorry that we are learning to view our colleagues through the possibility that everyone might be affected by mass psychic trauma, and adjusting our email salutations accordingly. I’m not sorry that we are learning that the pace of capitalism is incompatible with the pace of disability, which has been the pace of life for some of us. I want to move at a speed that doesn’t kill us.

VIII. Intergenerational trauma is the somatic reproduction of violence

I am so scared of people running away from their trauma right now because I am the anchor runner in a familial relay race of trauma so long that the racetrack spans generations. Overworking is a trauma response and overworking is also a way to avoid trauma responses. Overworking is the cousin of shutting down, the only two options available to us when we feel our sense of safety taken away.11 And truly, who can feel safe right now? How long must—no, how long can we live with our nervous system stretched between these two poles of total shutdown and total activation, without knowing what respite, connection, care, feels like? How long can we go without putting our hands to another person’s heart to let their breathing calm ours, and vice versa?

I am scared that you think this trauma will only last for as long until the economy reopens. I am scared that you think you’re OK. I am scared because my dear friend told me that in post-Katrina New Orleans, 2006 was the year the grief came, but 2008 was the year people who fought to hold things together started dying. I am scared that the unaddressed shock and grief of this moment will burrow itself so deep in our bodies that it becomes part of our cell tissue, and part of the cell tissue of future generations.

Remember that when we are fighting for the possibility of a future, we are also fighting to hold ourselves in all the messiness, the uncertainty of the present. For the sake of your future self, unravel.

IX. Disabled and queer kinship—making kin in the Chthulucene12

How many of us, honestly, live within a functioning nuclear family? Who is the nuclear family for? It isn’t for those of us who have been cast out of our families because of our sexuality. It isn’t for those of us who face legal barriers to adoption and other forms of non-heterosexual reproduction. It isn’t for those of us who have had family members deported, incarcerated, killed. It isn’t for those of us who are living on couches and spare beds to escape a violent home.

I think people of color, queers, and disabled folks are a little bit better at making kin than others. We know that the nuclear family is a conditioning mythology rather than a workable reality. We also know that making kin, making social bonds that catch us in a community safety net when we can’t access a social safety net, is how we will survive.

Pandemic asks us to seriously consider with whom we’re making kin. Who is essential, who is family when we can only gather in groups of six or less? Who is family not because of blood relation, but because of our mutual promise to care for each other? Who helps you reproduce, for real for real? Disability studies and transformative justice thinker Mia Mingus refers to this as mapping your pods. Apply adrienne maree brown’s theory of the power of the fractal to pods, and we might find ourselves emerging from this pandemic within a reorganized society of infinitesimal small units operating under care agreements.

I am hopeful that we will learn how to recognize and make kin beyond the limitations of blood ties. I hope that we see ourselves as existing within care agreements to care for a larger sense of community—and to care through loving, rigorous steps towards justice. I think that’s the only way that we can get through this. By recognizing our kin.

Carol Zou facilitates creative social change projects with a focus on racial justice, informal labor, and public space. She is a reproductive laborer, insofar as joy, connection, creativity, social change, and being the “cool aunt” constitutes reproductive labor. Current and past affiliations include: Yarn Bombing Los Angeles, Michelada Think Tank, Trans.lation Vickery Meadow, Project Row Houses with the University of Houston, Asian Arts Initiative, American Monument, Imagining America, U.S. Department of Arts and Culture, Spa Embassy, and Enterprise Community Partners with Little Tokyo Service Center. She believes that we are most free when we help others get free.

Notes

1. Quarantine reading: Revolution at Point Zero, by Silvia Federici

2. Quarantine reading: Social Reproduction Theory, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya

3. This is the premise of reproductive justice, a concept originally articulated by women of color reproductive justice collective Sister Song

4. Quarantine reading: The Necropolitics of COVID-19 by Christopher J. Lee

5. Quarantine reading: Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis, Golden Gulag, by Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba on twitter @prisonculture

6. Quarantine reading: 8toabolition.com

7. Shoutout to Auntie Sewing Squad and #3DPPEArtistNetwork

8. Quarantine reading: Take Back the Economy, by J.K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy

9. Quarantine reading: The Dispossessed, by Ursula K. Leguin

10. Instant Pot congee (粥): 1 part rice, 8 parts water. Pressure cook for 20 minutes. Natural release. Suggested toppings: Sesame oil, soy sauce, furikake, green onion, ginger, pickled vegetables, fermented tofu, fried egg, century egg

11. Quarantine reading: The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy by Deb Dana

12. Quarantine reading: Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, by Donna Haraway

13. Quarantine reading: Pods and Pod Mapping Worksheet by Mia Mingus, https://transformharm.org/pods-and-pod-mapping-worksheet/

14. Quarantine reading: Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown