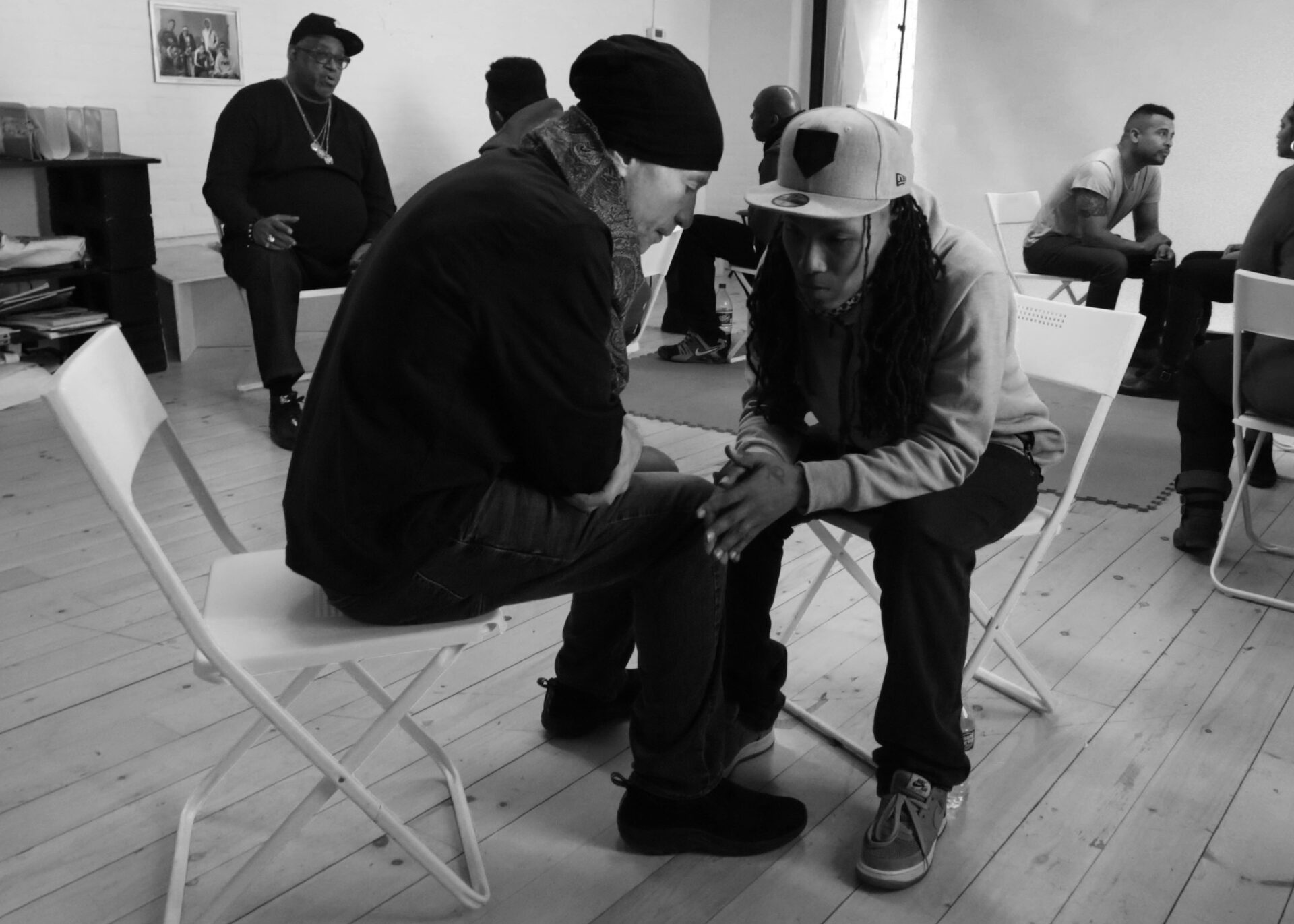

A Primitive Games workshop. Photo: Seyhr Qayum, Emma Seely and Lodewijck Kuijpers. Courtesy the artist.

Shaun Leonardo is a multidisciplinary artist identified with working on the issue of mass incarceration in the United States as much as any medium. This May, A Blade of Grass was to present the second iteration of his performance, Primitive Games, addressing the issue of closing Rikers Island jail, slated for 2026, at a public park in New York City. Throughout his 2019 Fellowship for Socially Engaged Art, the artist has been holding movement workshops with groups of people directly affected by the prison system in New York, both as a place of residence and work, as well as those advocating for reform. Postponing the performance has been devastating to the artist, whose motives are greater than just an artistic statement. Shaun, who was seeking an audience for his collaborators with the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, sees it as an opportunity for those whose lives will be most impacted by the jail’s closure to have their voices heard within the planning process. This, like many issues, has become one for another day as we stare down the direct, life, and death consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. For as long as we’ve been warned about the need to “flatten the curve” and physically distance, health leaders have advocated addressing this massive public health issue—first—with cohabitating populations like jails, immigrant detention centers, and shelters. On March 6th, it was reported that the first resident at Rikers had died—a parole violation that unfathomably carried a death sentence. On March 27th, the first officer died, with the Wall Street Journal calling the jail “among the most-infected workplaces in the U.S.”

With the performance on hold, Shaun has pivoted the project to respond to the urgency of reducing overcrowded jail and prison populations. Participants from his working groups, including formerly incarcerated individuals and corrections officers, have been asked to share their testimony on how they’ve been impacted by COVID-19, and equally important, what they would imagine as a more humane response. The goal is to gather stories and align them with the on-the-ground advocacy efforts of organizations within the Art for Justice Fund cohort, of which Shaun is also a grantee. This interview was edited and condensed and has been published in collaboration with The Art Newspaper.

Kathryn McKinney: Let’s just start off with a little background. You’ve been working on preparing for your second iteration of Primitive Games. Can you tell me a bit of how this performance has evolved from the first done at the Guggenheim in 2018 and why you chose the issue of Rikers Island jail closing to focus the performance on?

Shaun Leonardo: Sure. The noticeable difference in the workshop process is that I am not withholding any information this time around. So in the first iteration, part of the experiment was to see what would happen in this non-verbal debate if the group affiliations did not have a clear understanding of who the other “teams” would be. This time around, I wanted to see what would happen during the workshop process if that information was not withheld—if it was known from the beginning for each individual, and each group affiliation [knew] who consisted of the other affiliations. And part of the reason I wanted to do that was because, in the first iteration, one might argue that there was a safe distance from one another in terms of the different affiliations’ experiences around gun violence. For example, there may not be a direct relationship between the military veterans and, let’s say, citizens impacted by street violence. This time around, the core issue—experiences of and around prison—directly implicates all four of those groups in their experiences with one another. So rather than pretend, or I should say, rather than speak around it, I decided to go right to it and let it be known that there would be 4 to 5 affiliations involved and to name them. And what was evident already in going through the first phase of workshops is that the intensity of the narratives and the experience of the workshop was heightened because we could be so much more specific. So that was both a philosophical and structural change from the first and second iteration.

Now the reason why I wanted to dive specifically into the state of prisons, and more locally the closure of Rikers, has to do with my broader involvement in the justice system, that being the Assembly program, which is now 4 years in the running. Because I’m now known as an artist in that space, I’m quite often invited to a number of convenings to do with justice reform. What I’ve noticed is that the voices and the experiences that emerge in a setting like Assembly are quite often not included in these convenings for justice stakeholders. And as momentum amped up around the closure of Rikers, so much of what I sensed and saw was that there was a visioning process taking place, and rarely did I ever see those most closely impacted by those decisions involved. And so the ulterior motive behind this iteration was to sort of prove that those most closely impacted by something like the closure of Rikers could one, sit at the same table, and two, after an experience like Primitive Games, contribute to a collective visioning process, and that three, stakeholders could, in that moment, take a back seat, slow down and just witness and honor what those groups would have to say.

Everyone moves from a place of fear.

KM: Continuing this idea of an overlapping network of relationships, and the way that you’re bringing these different voices into the conversation, I’m curious to hear what you’re hearing from these groups, including formerly incarcerated people, correctional officers, criminal justice advocates, court-involved youth, and survivors of crime. As you’re saying, there’s sort of these direct lines of relationships where you might anticipate people are always going to be on opposite ends of the spectrum on issues. Have any shared sentiments emerged?

SL: So, to answer that question, you have to let me go off for a little bit. And it’s strangely going to correspond with, I think, our experience now with the dangers and scare of the COVID virus. I was in the middle of this workshop process, (without sharing any specific narrative, that’s not really my place to do) when it became evident to me that when you really dial down into the real and or perceived idea of prison, what emerges in the narratives, in any of the groups, is some notion of fear. I was looking to see if that would be the core emotional space conveyed through the body. What continues to be clear to me is that everyone moves from a place of fear.

Now for some individuals, that is a more direct experience of being caged, if you’re a formerly incarcerated individual. But if you’re a legal advocate, let’s say, or you’re a corrections officer, you’re operating from the fear of “am I doing the right thing?” Alongside that, if you think about survivors of crime, it’s a fear of continued harm, of being safe, and if you are a young person with prison hanging over your head, it’s a fear of the unknown. But when you really distill those specific experiences of fear, it looks very similar in all of these bodies. And that is what really is the intention of this piece. That when you start peeling away the layers of the specific narratives that have emerged, something becomes familiar. There is some common ground that may reconnect us to one another.

I had a few students from Pratt, where I teach, acting as an evaluation team, and before our process halted, we had a number of conversations because I wanted to understand what they were seeing in the background, observing in this evaluation process. And there was one thing that they noticed, this idea that in the mechanics of prison, and there’s really no other way for me to describe it, in the day to day the very first thing that is removed to allow the operation of prison to run is a sense of humanity. It’s what allows the prison system to move on as a business as usual. Whether you’re on the legal side or whether you are now in reentry as a formerly incarcerated person, or whether you’re young person being churned through the court system, or whether you’re a survivor of crime that has really been blocked from the decision-making process of, let’s say, what restitution or healing looks like. All of these groups are unified in that there is no humanity that allows them to connect with one another. And that’s what Primitive Games is attempting to restore.

And so, relating to COVID, we are all in a place where we’re isolated. We see for ourselves first hand what it feels like to be disconnected from one another and the fact that it is not natural. The sort of ironic and crazy thing about any sad parallels that I might give you in terms of where we find ourselves is that we’re now seeing the lack of humanity in what it means to be isolated from the people that you love. I don’t want to take too many liberties in making comparisons, but the very thing that we believe, or I should say that largely society has invested in, is this idea of rehabilitation by isolation, or retribution by punishment, and now we’re getting a glimpse, a taste of what that actually means. Furthermore, with incarceration, we are causing harm and are creating more violence in order to deal with harm and violence. I’ll stop there. I have more to say, but I’ll stop there.

A Primitive Games workshop. Photo: Seyhr Qayum, Emma Seely and Lodewijck Kuijpers. Courtesy the artist.

KM: Well, I might encourage you to go on a little bit. This will undoubtedly lead to a massive paradigm shift, but we don’t really know if it’s going to be progressive or regressive. In the way that you’re talking about this shared fear that’s embedded in movement, we’re all kind of moving from that place of fear right now, I think, too. What can artists do to push an agenda of equality, compassion, and dignity for all humans right now, and what could that mean on this specific issue?

SL: You said it. In moments of collective fear, what comes out at the other end is either a unified effort towards interconnectivity and empathy, or we move into a state of regression where the fear triumphs. And so, I’ll get to the artist part in a moment, I just want to give a quick plug to a number of organizations that have been incredibly eloquent, so I don’t need to restate what they’ve already dictated as the reasons why prisoners should be set free and for what factors and what motivating forces. This is a conversation that has been going on for years in this reform effort. And it’s just now that COVID as a death sentence in prison is amplifying the same kind of push for prison reform. Organizations collected under Ford Foundation’s Art for Justice cohort like Katal [Center for Health, Equity, And Justice]; Columbia’s Justice Lab; We Got Us Now; or Fair and Just Prosecution, have all been incredibly diligent and clear about describing how the dangers of COVID highlight the very reasons why we shouldn’t be warehousing people in the first place.

Just to go off a little more, one thing that many people in the justice field and reformers of the justice system will continue to really elaborate on is the distinction between what drives crime and what we as a society have decided to do to punish crime. And we’re becoming much more knowledgeable and capable of communicating things, so what’s fundamental and important to understand is that the drivers of crime used to be understood as “criminal behavior.” And for decades, we sort of heard about this innate criminal behavior of certain individuals. And now, we understand that isolation, shame, desperation is what truly drives a person to do harm or to doing things that are codified as a crime. And yet those are the same three elements we impose on bodies in order to punish them. We isolate them, we cause them to feel shame, and we remove them from anything and anyone so that they’re in a constant state of desperation. So we continue to strip humanity from these individuals and then believe upon exiting prison that somehow they will be prepared to reenter and contribute to society. We know that prisons just don’t work. They don’t work as a structure, they don’t work as a philosophy, and there are scholars, there are abolitionists, there are writers, there are stakeholders that are doing an incredible job of communicating that distinction, that failure, in society and in the systems we uphold.

So what does an artist do? Rather than reiterate the same thing, what I often find myself saying is, “ok, you now have this information, how do I create a different mechanism or vehicle for having that information really sink in?” I can tell it to you over and over again, but if it connects somewhere in your own experience, in my case, that’s almost always a bodily experience, if you can start to see and feel in your own body what it looks like to feel desperate, to feel shame, to feel isolated, then it will move beyond rational thought. You will start to tell yourself that prisons don’t work because you’ll find yourself closer to the issue in a different way. So that’s where I fit in. This methodology of taking information that would otherwise be lodged in your brain, that you would otherwise only be listening to—to allow that information to move into your body, so you understand and feel the loss of humanity. That is a different kind of motivator.

I think artists can insert themselves and be a champion of these dialogues. And I think when the time comes, what artists have to continue to do is reinforce this interconnectedness, this sense of shared humanity so that we don’t retreat back into fear. I think artists do that best. I can communicate an essence of what it means to be human, and that’s what I hope to do.

…the very first thing that is removed to allow the operation of prison to run is a sense of humanity.

KM: Absolutely. I wanted to ask you sort of a specific question and I think you’re hitting. So far, just 650 people have been released from Rikers as of yesterday [March 30th], and 1,100 people have been released statewide. There’s reporting that hundreds more are pending some kind of review, but as of yesterday, there were 167 inmates confirmed positive with the virus in New York City. So progress just appears too slow. Have you heard any good solutions about what you think needs to be done at this moment?

Editor’s note: As of the publish date of this article, The Intercept reports, “Of the more than 4,000 people currently detained at Rikers, at least 365 have now tested positive for the virus, as have 783 Department of Correction staff and 130 medical workers.”

SL: Unfortunately, it is moving too slowly, and one would argue that we as a country move too slowly, that we’re about two weeks behind what we should be doing. And the 1,100 that have been approved for release are those that have been detained for non-criminal, technical parole violations. About 4.5 million people in the United States are on probation or parole supervision — double the number of people locked up. An alarmingly high and fast-growing number of people are sent back to prison as a result of technical violations, which are typically minor infractions, such as failed drug tests or missed curfews. The release of that population seems like the obvious first move, especially given that many of them are older and, therefore, vulnerable to COVID. Advocates are pushing for sentences to be commuted for all older folks and anyone with respiratory conditions or immune deficiencies, particularly if they only have weeks or months left in their sentence.

Also, anyone that might be a younger person that could qualify for diversion or other community-based practices. If you were to look at factors like these, the number of those released would be much larger. But what blocks it, again going back to our initial conversation, is fear. [Governor] Cuomo, I’m certain, and everyone else that might be in the position to make these decisions, are terrified about what it might look like if someone is released and then causes harm. And so it is important to look at how our government’s lack of willingness to move more quickly on the release of detainees and prisoners is connected to how mass incarceration was constructed, to begin with. It has been ingrained in us to believe that only “bad” people get put away. The prison system predicates itself on being invisible and is upheld by us, those on the outside, conceiving of it as somewhere outside of society, and therefore, not our problem. And so the idea of releasing prisoners causes terror in people because we’ve only been taught to see these individuals as less than human. And again, we’ve been instructed to believe that punishment is just. That is why it moves slowly because we haven’t done that work to dispel those beliefs and our notions of criminality.

KM: I think what you’re hitting on is this false idea that it might be bad for them, in prison, but society is safer that they be kept locked up, when in reality what happens when you have a population of thousands in this incredibly vulnerable situation and everybody gets it, then you have rural hospitals that are overwhelmed in the places where most prisons are, you have New York City hospitals that are already overwhelmed, you’re going to be dumping in thousands of patients, unnecessarily. A whole other wave, even as we’ve been doing everything to combat the overall wave outside of jails. It’s again sort of this false notion that we can be safe while other people are put in harm’s way.

SL: And that it will be contained. And alongside all of that, the way that it impacts corrections officers, all the medical professionals that work inside prisons that will go home to their families—this notion that prison is separate from society and therefore not our problem. We’re beginning to understand now, again, because of all the communication and vigilance behind really getting the information out, that the health of those in prison is very much connected to society and that the impact of the spreading disease on the inside will spill over to the outside. And you know, alongside that people always seem to forget that the majority of residents in prisons and jails will be released. It’s just a matter of time. But in our collective consciousness, we believe that once people go away, then they’re not our concern. And so to empty out prisons should connect both to the tragedy and horror of COVID but also a larger discussion of the injustice of warehousing bodies, to begin with. We have to continue to talk about COVID and the impact on these human beings, as human beings, and the ways in which it points to the already existing failure of prisons.

KM: That’s a great place to end this conversation, but I did want to just point one thing out because I think it’s part of this conversation that’s really being missed. And the basis of your working in the criminal justice system was through your youth diversion program, Assembly. So something we’re not hearing a lot about is youth in detention, and I think it’s important to speak to that a little bit.

SL: Yeah, thank you, thanks for bringing that up. I mean, New York in particular and specifically Brooklyn, has done a better and better job of lowering the numbers of youth detained in New York City. So it doesn’t surprise me that it’s less a part of the conversation. The media continues to state that younger folks are less vulnerable, forgetting that impoverished communities, communities without resources, are also those that have been, for generations, left behind by the healthcare system and therefore are more vulnerable to disease and illness. So our young folks are often going back to communities in which they are not cared for holistically and therefore remain vulnerable.

The crazy thing is that because of how COVID has impacted my family directly, young folks that I work with, express worry about me. And so they’re calling me and checking in on me when at the end of the day, they’re more in need. It never ceases to surprise me how the phone calls and text messages that I have received and those that are caring for me most are from those folks that society has left behind. The formerly incarcerated folks that I’ve been working with, the court-involved youth that I’ve been working with, those have been the first individuals to call and text me to see if I’m ok.

If I were to put a sentence at the end of it: they know what it feels like for someone not to care.