A nuclear reactor pool in the now-closed Barsebäck Kraft nuclear power plant in Sweden. Photo by Knut-Erik Helle.

Art is an effective vehicle for expanding empathy and challenging our sense of what’s possible because art is a space of imagination. And this maxim that I keep coming back to in my own work as an institutional leader is that the art is not the institution. Art and images are sparks that ignite the mind and soul. Art takes us on the journey, and must be able to challenge us–even to the point of disturbing us or making us feel unsafe. How else are we going to be able to do brave things like examine our closely held beliefs, love more people, or imagine a future that’s better than the present? The institution’s role, though, is not to be the spark, or to do the disturbing. The institution needs to honor, hold, and enable the capacity art has to make us feel unstable or unsafe, or it would lose its purpose and its moral center. But it can’t be unsafe itself. In fact, the opposite–the institution needs to prioritize safety because its role is to help the artist realize the journey; sign people up for it and hold them through it; make sure enough people value it; and put it in a larger context so that its meaning might be enhanced and shared.

This role, and its fundamentally receptive and nurturing nature, informs the social and political work that an art institution can do. This is important to clarify for two practical reasons. First, we are living in a moment in which popular culture, media, and images are incredibly powerful, and are being wielded in a high-conflict, unstable way, to significant social and political effect. Look at the outrage and proliferation of fake news on your Facebook feed, or the abundance of journalism about what the POTUS is tweeting for examples. The intensity of this broader cultural exchange, and what’s at stake in it, are relevant to art institutions in a tautological way—it feels almost dumb to clarify that art is part of the culture, and art institutions are cultural institutions. But there’s more to it than that. I want art organizations to get in on this moment in a productive, proactive way—not as a target of protest, or as a mere amplifier of the malignancy and intensity, but as a helpful transformer of outrage and anxiety into meaning and connection. I think that this work would have tremendous value, and art institutions are facing a crisis of value right now. 65% of my job is fundraising, so I mean this literally, in terms of who pays for art and why. Art for art’s sake wound up being a relevant value proposition to a very small handful of people. We know that art, and the art institution, is not just relevant “for its own sake,” that there’s civic and social value in the images we make and our collective imagination. But we struggle with articulating that value clearly and taking it seriously.

I want art organizations to get in on this moment as helpful transformers of outrage and anxiety into meaning and connection.

So, if the broader cultural moment is powerful, unstable, and full of cultural conflict, and if art is a challenging, potentially unsafe encounter that can transform us, let’s say that art institutions can do their best work when they manage and hold all this power and instability; transform it into meaning and connection; and then productively channel that meaning and connection into increased collective agency for as many folks as we can. This is the kind of relevant, growth-oriented, inclusive work I want to be doing as an institutional leader—it takes art seriously, keeps the art dangerous, and prioritizes relevance! To get organized around doing this work well, I want to spend some time with a metaphor. Let’s pretend that the art institution is like a nuclear reactor,1 and that its work is to generate and harness the effects of what we could call “cultural fission.”

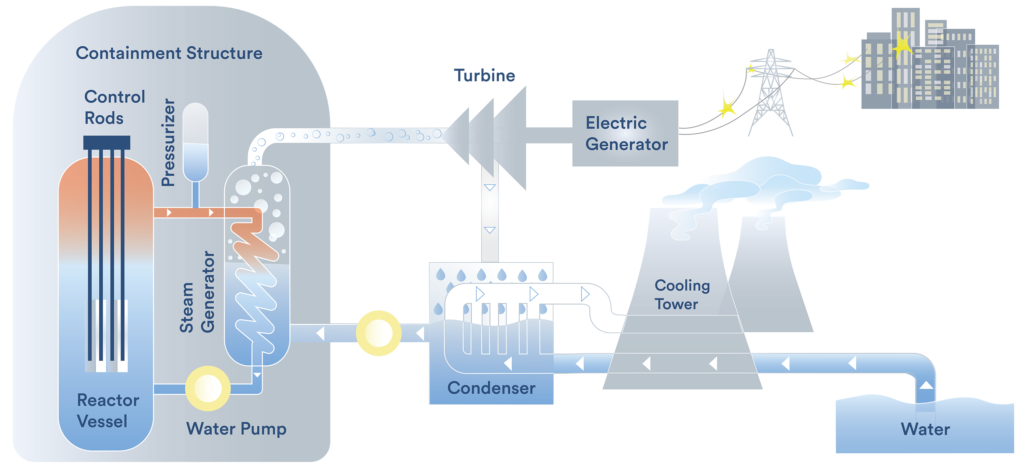

A nuclear reactor harnesses the energy created by a chain reaction. Pellets of uranium are hit with neutrons. This causes the nucleus of the uranium atom to split apart, and as it splits, it throws off a lot of extra particles—this is what makes it radioactive. Those particles then hit other uranium particles, and they split, throwing off more extra particles, and so on. Chaos ensues! Particles keep hitting particles, and this produces more and more heat. Nuclear reactors are designed to control this chain reaction, and use the heat that gets produced to power a steam turbine that produces electricity.

As “cultural engineers,” we are not starting with a relatively stable situation—unprocessed uranium is mostly harmless—and then making it unstable by putting it into a sealed container and smashing neutrons into it to start a chain reaction. Instead, we are noticing that there’s already a somewhat dangerous uncontrolled chain reaction going on all around us every day, and suggesting that it’s a good idea to bring it into the institution in some way. Each image of children in cages, story of yet another black person being treated unjustly by the police, 20-person unite the right march, bizarre presidential tweet, and meme of Ivanka Trump photoshopped into an important historical moment is, in and of itself, small. But they are also each unharnessed, unprocessed, unstable, throwing off extra heat and unstable particles. They are also highly reactive—pelting us with energy, and generating more and more of themselves. Memes beget memes. Bizarre presidential tweets turn into a flood of media coverage about the tweets. Actual news stories that feel offensive and hard to believe on both sides of the partisan divide spawn even more divisive fake news. Right now, all this unstable, radioactive cultural energy is mostly gathering on one another’s social media feeds and popular media, where the kind of power it generates is outrage and anxiety—which feel poisonous. I have to admit that this is a risky start! If I were a board member, I would be really worried if my Executive Director was like “what we need to do is bring all this stuff that feels bad into our work.”

Illustration of a nuclear reactor based on GAO and Nuclear Regulatory Commission documentation. Image by Karina Muranaga.

Here’s why I do actually think it’s a good idea. First, I think that cultural institutions are going to be better at transforming the culture than engaging in partisan political speech or enacting a policy agenda. How we engage ideas, whose ideas are represented, and what kind of society those ideas and images walk us toward are all fair game for a cultural institution. And people are getting hurt by ideas and images now! The outrage and anxiety that comes out of engaging right now are painful, and they propel too many of us into hurtful, antisocial behaviors like shaming, deplatforming, yelling at people in person or online, firing your babysitter because you don’t agree with her political views, deciding you can’t do Thanksgiving, driving a car into a crowd of people you don’t agree with, or stockpiling weapons with the intention of creating a militia. Institutions enable collective action—they are what we decide to do and believe together. If what we need to do together is relieve one another of all this shame, hold a lot of conflict, or remember how to disagree, then institutions should rise to that occasion. Even if it’s scary.

If we can all buy that we want to start working with this uncontrolled cultural chain reaction that is spitting out all these outrage and anxiety isotopes because it is doing harm, then the next step is to figure out how to work with it in a way that has a shot at actually reducing harm. Here I think we can find some good news. There is very little that a very large institution like the Whitney or the Met can do to proactively or productively engage this moment because their board members and donors are already targets of protest, and their business model is built on high-level participation from the Sacklers or Warren Kanders. Smaller art institutions are similarly dependent upon wealth and philanthropy, but with a completely different set of stakes, and using a different value proposition. Simply because smaller organizations are less dependent upon exchanging very large contributions for social capital2, other opportunities to articulate value can arise. Many smaller organizations are already taking advantage of

Institutions enable collective action—they are what we decide to do and believe together.

this flexibility by integrating community and cultural organizing, social practice artists in residence, and talkbacks and other more dialogical programming formats into their work. There are also more and more examples of institutions asking community members to curate exhibitions or otherwise drive programming. This is an important shift because it moves beyond talking and relationship building, and into actually sharing institutional authorship and authority. I think that all of these existing programmatic strategies can be broadened beyond the scope of the art world and its discourse, and start holding and serving a broader cultural agenda that does things like use art to put people who disagree with one another into a productive dialogue. Using art and art institutions for this work creates an opportunity to work obliquely. While a historical or civil rights museum might bring a constituency deeply invested in an issue or history, an art audience might be seeing a new idea or new material. It also creates the ability to broaden institutional networks and partnerships. An art institution can responsibly hold a cultural moment full of conflict, but it cannot responsibly hold the depth of the histories or civic issues that are coming up all by itself. The only way to meaningfully engage difficult discussions about race, colonial history, economic oppression, environmental justice, and so on, is to partner with organizations outside the arts.

To deepen these sorts of programmatic commitments safely and transformatively, we would need to consider the structure of the institution itself, and how it holds and nurtures the programming it creates. In our metaphorical reactor, nuclear fission happens inside a containment vessel filled with water because the water slows the particles down. The heat in the reactor is controlled using these things that are, unmysteriously, called “control rods.” Various chemical reactions are monitored and fine tuned to maintain equilibrium. It’s true that programmers of art institutions are developing some facility with holding consequential conversations in considered spaces, and a matrix of consciously developed community that, like the water in a nuclear reactor, cools and slows reactivity. I would also argue that the board of directors of any nonprofit should consider itself a set of “control rods” that keeps the nonprofit safe and productive—not by shutting conflict down but by understanding, participating, and supporting it, and also by letting conflict inform the institution’s work. I would also suggest that the purpose of good governance is to enable the leadership of nonprofits to ensure that everybody is working in balance—toward shared values and goals, instead of trying to extract value from the nonprofit as an individual. Taking in this cultural moment, with its hyperproduction of images and memes and outrage and anxiety, would not require art institutions to do different work. But it would require art institutions to take aspects of their work that currently don’t get much attention, like board culture, governance, and education, much, much more seriously.3

Once we’ve got a compelling why, and have invested in a “control rod” type board and donor base that truly understands what we’re doing and has our back and is consistently walking their talk, and have perhaps committed to a little inventory of all the assets we have in the form of programmatic strategies or experiences with letting our stakeholders inform our work, then it’s time to push this metaphor as far as it can go. How much can an art institution prioritize productive, humane conflict? Is there a point at which this starts being generative? How many human resources can be devoted to relationship management and trust building across the entire stakeholder map that makes an art institution possible? How can we go beyond simply enabling conflict, which feels a little too easy right now, all the way to diving into the proliferation of images, memes, and commentary that the institution itself cannot control? How do the art and the culture get plugged together? There are types of diversity that feel easy to achieve—like getting poor artists and wealthy collectors together—and others that feel really hard, like getting people of color onto boards, or conservatives and liberals into the same exhibit. How diverse can outreach get—how diverse can we get in our thinking about diversity? And… I think this is the most important and delicate question of them all:

What is the institutional perspective that meaningfully responds, consolidates, shapes, and directs all this debate and imagery in a way that does effective political work but does not simply collapse into taking a side?

This is the question that really makes the metaphor work. It is a question that is accountable to harnessing the heat of this cultural moment to create the next cultural moment. And to do that, the institution needs to have some values that it is willing to not just articulate, but deploy. The institution needs to be thinking clearly about who it is inviting to participate, who has a voice, and whose images matter; what types of conversations and encounters are being shaped; what art and an art context do to shape these encounters–why art matters in them; who is holding the encounters and the larger networks they might feed into; and what happens when we disagree. That’s not partisan work—cultural institutions are not for liberals or conservatives. But it is deeply political work. Culture in this framework is participatory, the business of every single person who touches the institution. This is already how culture works—we imagine the future when we watch TV or listen to music. In an art institution, we can slow this process, examine it, make the reactions into reflections, take the time to make decisions that are more loving or just.

Notes

1. This is a metaphor, not an endorsement of nuclear power.

2. Or less able to! A Blade of Grass, like many art institutions its size, certainly goes through the motions of hosting galas with honorees and otherwise tries to use this business model. It’s just not effective, in large part because we are competing in the same social landscape as the New Museum, the Met, the Whitney, MoMA, and so on.

3. This is actually not a hypothetical for A Blade of Grass. While we are not yet harnessing cultural fission, we do work with challenging artists who are enacting change in the world. Sometimes we bump up against legal issues, the fear of physical violence or reputational damage, our own accountability to structural oppression, and so on. We could not do our work without a small, empowered, fully educated, deeply engaged board that does act as a healthy and functional set of “control rods.”

4. Future essays will further draw out both the work and potential business models for this type of institution. For now, I think it’s important to simply clarify that you can’t do this work if it threatens funding.