Diego de la Vega Coffee Co-op, image courtesy RAVA films.

Artist and 2014 A Blade of Grass Fellow Fran Ilich’s Diego de la Vega Coffee Co-op is a collaborative project that connects Mexico’s Zapatista communities to service industry workers in New York City. The Co-op serves Zapatista-grown coffee from Chiapas, Mexico at social movement meetings, events, and rallies throughout New York, using the pop-up as an opportunity to share ideas about the Zapatistas’ alternative economic systems, pre-Columbian indigenous ways of life, and anti-capitalist rhetoric. A Blade of Grass Programs and Communications Manager Joelle Te Paske had the chance to speak with artist Gabriela Ceja, a primary collaborator in the project, at Open Engagement in Pittsburgh in April 2015. Gabriela introduced Joelle to some of her work and shared her own experiences of working on the Co-op.

This interview has been edited for length.

Joelle Te Paske (JTP): You are a large part of the Diego de la Vega Coffee Co-op, and you are also its artist-in-residence. I’m curious about how you got involved in the project.

Gabriela Ceja (GC): I was invited to work and collaborate with the Coffee Co-op and in exchange to do a residency in New York City. When I started my project, I was interested in the indigenous people who came to Mexico City [where I was living] to work in construction. I interviewed people who were living in the buildings in which they were working. I started to create relationships with them. That’s how I think, as artists, we can really try to change reality, when we try to transform the way we relate.

The opportunity to do the project in New York City was great because I could be involved with workers from all over the world. I could trace what the workers from my own country were doing there and the conditions that they found. I met this construction worker from a state in Mexico called Michoacán. He worked as a grape picker in California when he was fourteen. Then he moved to another state, I think it was Georgia, to build roads. After that he moved to New York City and he worked in elevators. He was only thirty years old, and he had worked since he was fourteen.

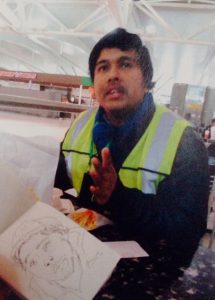

I tried to trace their lives and see why they moved into cities. Labor shaped their lives. It gave them the path that they followed from a very young age. At JFK airport, I met this other guy from Bangladesh who had an MA in social development in his country. He was a very smart person who had lots of ideas for projects. He said he was interested in taking photographs of landscapes changing with industrialization, and that he wanted to do a documentary about the careers that were going extinct in his country. But the most surprising thing was that he was working as a janitor at JFK.

In these people, I see all of the problems that the system has. The incoherencies. What is this person doing here? Why does he have to go through these life paths? To have this incoherence in life—that he’s so well prepared, and he’s working in this place.

Mishu, who has an MA in social development from the University of Dahka, Bangladesh, works as a janitor at JFK airport. He tries to work on independent projects every fifteen days. Photo: Gabriela Ceja

JTP: What has been the most meaningful part of working with the Diego de la Vega Co-op thus far?

GC: Everything about the project has to do with constancy and a kind of humble activity, and doing a radical thing with a simple activity, which is serving coffee. The most meaningful part for me is being part of the global economy and actually moving a rebel cause that concerns the indigenous people I care about. I’ve seen them suffer. My own family is part of that. So through a product we can move an idea. It’s very material. What I love about the project is that it materializes into people’s bodies and people’s minds and real conversations.

JTP: That makes a lot of sense. It’s a beautiful thing, because it’s not a grandiose philosophical idea—even though it’s connected to those things. At its essence, the coffee is something from the earth that someone grew. You drink it. It gives you sustenance in some ways. It provokes conversation.

GC: I agree with you. The coffee—it’s a whole process. We are trying to be coherent in the whole process of ideas and political things, which are so important in our country right now. We think about the Zapatistas and what they’re trying to do, and what social movements try to do. We think about these communities who are actually living differently and being autonomous. The way we can help is by distributing the coffee they sell. Sometimes we can be very, very idealistic and think we can change the world, but if we try to do it by ourselves, we can only make very local changes. Those are important, of course. But if we contribute to a cause that is actually working [laughs], that is a little bit more realistic.

Maybe the Zapatistas are out there working in the fields, but they do not have distribution means that normal coffee companies have. They cannot distribute their product the same way. For that, there’s a voluntary network of people, including us, who will help them. Then we can also have this other alternative economy that helps us produce other materials, such as narratives and maybe artwork.

The most meaningful part for me is being part of the global economy and actually moving a rebel cause that concerns the indigenous people I care about. [ . . . ] What I love about the project is that it materializes into people’s bodies and people’s minds and real conversations.

JTP: It also helps people to see an alternative. I think it is refreshing to see a different sort of economy working. It is important to know that there are alternatives, even if just as models.

GC: We worried a lot about that part. We really wanted it to work, but then it is a model. When is the model going to become reality? It needs a lot of work and concentration.

JTP: You can take this question however you’d like to, but where is the art part of it for you?

GC: The art part comes in with this change in reality we are trying to create. Look, there is a performance every time we serve coffee. It’s a very poetic idea, no? The coffee is what awakens your awareness. It symbolizes conversation. It stimulates intelligence, whether you’re alone or whether you’re with people. The poetic aspects of coffee and its historical symbolism are political. We thought about making packages and selling them, and making some prints, but the whole thing about serving the coffee as waiters is an important aspect of our statement, because we are always aware of the service position that so many Mexicans have in the United States. It is an ironic way to present this project.

JTP: Yes, and reclaim it a little. I do see a lot of performance in what you do. You could package it up—but no, you don’t want Diego de la Vega Coffee Co-op at Whole Foods, with a little screen-print.

GC: [Laughs] Do we want that? We were wondering. We were actually really wondering—maybe that will work better, though? Distributing it to stores so that normal people can consume it. But it didn’t make sense with the Zapatista movement, because they share it only with people who have ideas in common with them.

Diego de la Vega Coffee Co-op, image courtesy RAVA films

JTP: Now I’m curious—how do you think that would change the art part?

GC: I don’t think it would change. It would change the way it is delivered, but it would still be art because we are transforming relationships. We are reinventing economic relationships. We are using the imagination of the artist to reinvent reality. That’s the power we can get, because we are not economists. We are people—creative people—who want to intervene in reality.

JTP: I feel like you decided the performance part of it was the best way to be a part of those relationships, or change those relationships in the way you wanted to.

GC: Well, I don’t know if it was the best way to change relationships. Yes, it was a way to communicate with other movements, just by being part of them. And we don’t know if it was the best way to have the coffee distributed as well. But it was the most joyful, maybe.

The performance is like a service, and in a way it is like a ritual. It is so many things that involve presence. It’s great because we force ourselves to be part of things. Ordinarily, your attention span is such that you consume whatever you can at events, and then leave. But we were at events from the beginning and we would meet people in a different way. Like, “Where are you organizing? How am I going to serve the coffee?” We were there when they were closing, so everything became different.

JTP: You become part of their whole process. You were there when they started; you were there when they finished.

GC: Yes. And you would have a different conversation. You would become familiar to people in your own way.

JTP: What are your hopes for how the project continues?

GC: Many! [Laughs] I believe this was just a beginning. It helped us really organize ourselves to see how it would work. I think that the idea of having the catering service is great. It is practical because we can just decide the dates when we were going to serve the coffee, rather than have a coffee shop and be there all the time, expecting people to come. We go to the people and we go to the events.

Joelle Te Paske, Gabriela Ceja and Fran Ilich at Open Engagement, April 19, 2015. Photo: Ellen Staller

Gabriela Ceja is an artist, researcher and educator. She explores working environments in Mexico and New York City in order to amplify the voices of people whose life paths have been affected by classism, racism, exploitation and alienation. Believing that art and education are tools for social change, she also designs programs that blur the boundaries between disciplines, institutions and publics.