Deep Space Mind workshop prompt. Courtesy of Ras Cutlass.

Editor’s Note

__

As a 2019 A Blade of Grass Fellow for Socially Engaged Art, sci-fi writer, artist, and social worker Ras Cutlass is embarking upon Deep Space Mind, a collaborative space where Philadelphia communities work together to design innovative, alternative mental wellness systems through the use of science fiction and Afrofuturistic creative processes. In this article, Ras shares how she came to develop the Deep Space Mind project as an alternative to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual currently utilized by the mainstream mental health field to diagnose, stigmatize, and confine communities that suffer from generations of disenfranchisement.

Some of my earliest memories are of visiting my brother in residential treatment centers, psych wards, and group home placements. I learned to tie my shoes from a clown doll that I now recognize as a sensory stimulation toy that he found during one of his placements.

In the numerous times when our communities and families could not bear the brunt of whatever mental spaces were taking up our home, institutions and systems were always there to consume us. It was not until fairly recently, in therapy, that I realized how temporary my relationships had felt as a child, and how my ability to stay in my home with my parent was conditional to how externalized my inner turmoil was.

I watched my family members cycle in and out of institutions during the most stressful periods in our lives—through unemployment, grief and mourning, displacement, civil unrest—and I began to internalize the ever-present message that my legitimacy as a free person was contingent on the management of emotions that set off alarms in others.

I watched my peers get dragged to far-off places meant to correct their behaviors and personalities to be more palatable to systems, particularly schools and families. Yet I knew kids had outbursts about feeling dumb, being made to read out loud, or because other kids were goading them. They were truant because they tended to their siblings in the morning before managing their own needs, or because they were manic or depressed, or because their parents were. Kids fought other kids to have control over something in their lives, or to lose themselves in a moment of victory in a reality where they had little opportunity to feel that way otherwise.

But it seemed the only solutions society had for my peers were to remove them from class, remove them from community, and warehouse them in out-of-home placements or juvenile or criminal detention centers.

In the numerous times when our communities and families could not bear the brunt of whatever mental spaces were taking up our home, institutions and systems were always there to consume us.

My first therapy session was as a seven-year-old alongside my dad. A white man, Dr. Ferguson, sat across from my father and me during one of my mother’s more dramatic hospitalizations. He had been our family’s court-appointed psychiatrist since I was a toddler, and for the first time I was able to experience his bullshit in person. My father and I sat with massive shock following my mother’s latest episode and had received little support from law enforcement and the healthcare industry. I remember wondering how Dr. Ferguson would help us first—would we get emergency funds to repair our townhouse so we could get our security deposit back? Would my dad get some kind of worker to help him manage my mom’s condition?

But the first thing Dr. Ferguson asked was, “Do you love your wife? Do you ever hug her or tell her you love her?” As a seven-year-old child of Caribbeans I knew better than to say anything or show any emotions, but I was absolutely aghast. It was such a mismatch with our needs at the time and such a mismatch with how we even operated culturally. And as I understood bipolar disorder at the time, her episode had not been triggered by a lack of affection. Instead, the anniversary of my oldest sibling’s death due to gang violence had incited her mental state. And somehow, that entire piece of our history as a black family in Southern California was lost in favor of what I felt was a white theory on our family’s struggles. My father’s resulting irritation might have resulted in child welfare investigating him a few days later.

For me, these experiences with mental health services—and all the entangled systems and spaces of confinement that exist for Black, brown, queer, and poor people—were pivotal to my own development as a Black child. My culture, socioeconomic reality, and lived sense of what was necessary for our mental wellness when I was a child stood in stark contrast to what representatives of that industrial complex felt was going on with us.

As a Black AFAB person, I continue to have difficulty experiencing anger, excitement, intimacy, sadness, or eagerness, especially in the presence of others. I can picture a long road to each of these emotions, and all of the milestones in between, that make up my relationship to them in the present. I can see the long distance I have to make it to anger, and the vulnerability I feel on that long, dark road. Because in anger there is protection, self-defense, confidence, action. And being slow to anger also means being wide open for attack.

So while for a long time I felt privileged to not have “anger issues”—the same kind that caused my brother to fight and enter the school-prison-pipeline, or my mother to curse out her boss and lose her job—I have come to seek balance in all psychic relationships, including my relationship to anger and rage, which seem so far away, but offer great benefits in safe access.

Another aspect of my psychic life that I value greatly is my ability to organize my own introspection visually in a pretty consistent way. It makes for good metaphors in writing, but also helps me process information about myself with more clarity, distance, and peace. For this reason my dream world is very rich and consistent, and provides for me a sense of home or place when I am sleeping and attempting to process all of the new data and experiences I collect throughout the day.

It’s this “visioning” that I employ in my science fiction writing and practice. Being able to clearly visualize futures for myself and the pathway towards them has served as a source of conjuring for me—a way to heal myself and those that inhabit the future with me.

However, this visioning—and perhaps how I came to develop it—has a dark side. I live with post-traumatic stress disorder, with intermittent periods of recovery or relief. Dissociation is by far the major way that PTSD lies within me. I have a strong ability to manipulate my relationship to my body and reality, because of times as a child when that was my only respite from pain and escape was not available to me. There is no road to dissociation for me. Dissociation would be my home in my own mind space, and in my 20s I explored that home thoroughly by working as a frontline mental health worker getting an hourly wage, and being unable to afford the therapy and treatment I needed.

Dissociation became a case study for me in neurodiversity, or the idea that instead of disorders and sanity, human brains are simply different from one another, with pros and cons to each state, regardless of our characterizations of those states in the modern mental health industry. It also put me on to what might be called psychiatric phenomenology: legitimizing the experiences of people whose realities may not be apparent to others.

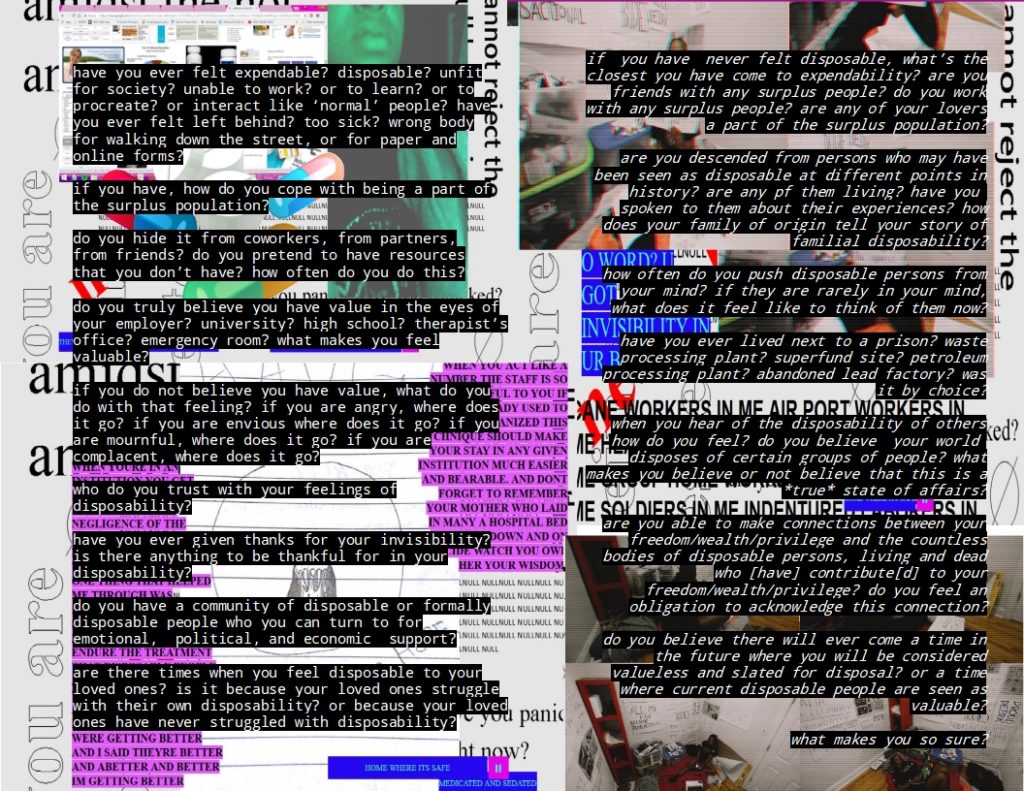

“Surplus Person Questionnaire” Excerpt from Style of Attack Report by Metropolarity. 2016, Philadelphia. Image courtesy of Ras Cutlass.

It relieved so much shame for me to learn about dissociation as a state of the human mind that we all access at one point or another, with the capacity for mundane experiences like being “in the groove” during a game, or beautiful transcendent ones at church or during sex. That relief and respect for dissociation allowed me to develop a much more intimate, healing, and transformative relationship with it. Today I even consider it a superpower.

These trains of thoughts led me to develop the first Deep Space Mind workshop, initially created as a one-time engagement during the Afrofuturism Now! Festival in Rotterdam, Netherlands in 2015. I had been creating and carrying out writing workshops in the US with other members of Metropolarity, a sci-fi collective, and had followed Rasheedah Phillips [of Black Quantum Futurism Collective and Metropolarity] to the Netherlands to test out Deep Space Mind before bringing it back to Philadelphia.

With Deep Space Mind, I wanted people to have a space free from the scrutiny of society and systems to simply get to know the architectures, landscapes, soundscapes, and any other organization of their own minds, with the goal of decolonizing and destigmatizing the structures that make us unique and alive. Now, I hope to scale that up and address the collective psychic space we share, illuminating the power we have to impact our collective consciousnesses through vulnerability and building together.

By creating our own designs for mental wellness and peace, we get away from looking only to large systems and poorly accessed credentialed professionals for treatment; but also to our neighbors and community members who may have gifts they can offer to our wellness and vice versa. I don’t know yet what Philly communities will come up with for Deep Space Mind, but I know it will bring together the massive power of mind spaces that are flexible, resourceful, cunning, passionate and effective, as I know my neighbors to be.

Meet Deep Space Mind Program Associate Dominique Matti, Philly-based writer, editor, healer, and mother of two

“I will be supporting Deep Space Mind by focusing primarily on communications and group co-facilitation with Ras Cutlass. What most excites me about participating in this project is the opportunity to archive the ways we tend to one another under systems that root for our isolation. There’s no shortage of documentation of how we’re held down. I believe it’s imperative that we train our eyes towards reverence for the many ways we hold each other up, and how we forge spaces where the core focus is our collective wellbeing.”

Excerpt of “Melinda and the Grub” by Ras Mashramani [also known as Ras Cutlass] from Procyon Science Fiction Anthology, (2016) from Tayen Lane Publishing.

In the morning, there is a man in a starched white coat sitting at the foot of her bed. He looks angular and large in the room, where the walls are dusky pink and her artwork and family pictures are taped over the bed. He begins to ask her about her stay, and about her family, how she’s feeling.

“I miss Philly,” she says. “I’m ready to go home.”

The man scribbles in some journal. “It’s only been three

weeks,” he says, “What makes you so sure you’re ready to go home?”

Melinda keeps being reminded that her opinion about leaving the institute means nothing. A tech had said something the other day when she threatened to smash her head through the medication window if she couldn’t get another Wistarel. “When I write my daily tonight,” the tech had said, “Should I write ‘Melinda patiently waited for her nightly meds despite being upset,’ or ‘Melinda smashed her head through a window and had to be placed in restraints?’”

Melinda softly thudded her forehead against the glass, “Oh my god, Miss. It is not that serious.”

So Melinda thinks she knows what the man is getting at—does she make everyone’s job easy, or is she going to give them a hard way to go.

“I been acting calm and I started going to sleep on time without cursing everybody out. And I don’t even care no more that I was taken,” she mumbles.

“Taken?” He looks blank, yet somehow cheery, waiting for the punchline to a joke he won’t quite get.

Melinda frowns, feels her breath hitch in her throat. “You know,” she says.

The man leans in, “I’d like to hear the story that got you here. The story all you girls have been telling. Because the way out of the institute is through me. I’m who you have to convince.”

Melinda searches the man’s face now and finds some kind of bureaucratic hardness, like her mother’s worker at the social security office, like the school counselor, like Tashira’s advocate who monitors her blinking ankle bracelet since three months ago when they caught her running away.

In any case, the man in white is waiting.

“Surplus Person” project exhibited at Time Camp 001 curated by Black Quantum Futurism Collective, 2017 in Philadelphia, PA. Digital and Print media. Images courtesy of Ras Cutlass via GIPHY

Ras Cutlass Mashramani is a Philly-based sci-fi writer, narrative artist, and co-founder of Metropolarity, a local grassroots sci-fi collective. Her artistic work concerns the experiences of people who are subject to institutionalization and dehumanization because of mental wellness challenges, being of color, or possessing another marginalized identity that proves dangerous to the status quo. In another life she is a social worker with over ten years of frontline mental health experience, currently organizing young people to take the lead in local housing justice and community healing work.